Die Antwoord has been millions of fans? #YourFaveIsProblematic problematic fave for nearly a decade, by this point. Admittedly, I was one of those millions, although this admission is not without remorse; Die Antwoord (and previous related projects) are one of the most socially, politically, and culturally divisive and problematic music groups of the 21st century.

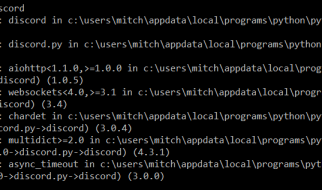

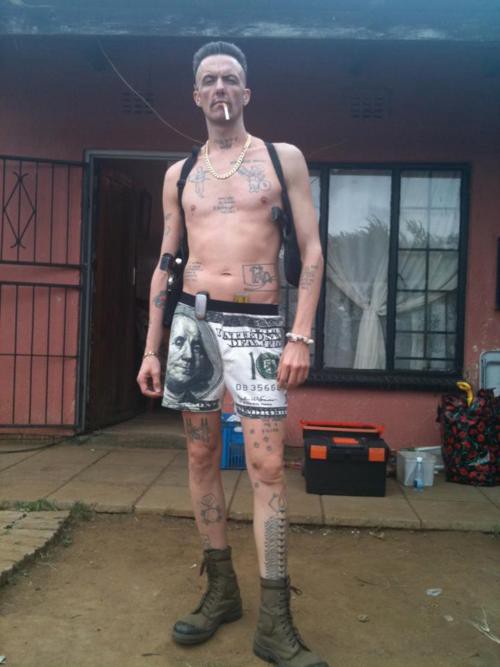

As South African media ambassadors to the West, they have come under fire for wearing blackface in multiple music videos, and appropriating cultural staples of South African ethnic groups for entertainment and profit. Some South Africans have publicly denounced their support for Die Antwoord and its two main members: Watkin Tudor ?Ninja? Jones and Anri ?Yolandi Visser? du Toit. There is something exceptionally racially disturbing about two privately-educated white South Africans commodifying post-Apartheid Xhosa and Afrikaner culture, in order to market it to other colonized nations. Yes, I understand that Yolandi herself is Afrikaner. I also understand that she is in a group with a man who does not share that heritage and has claimed that racism in South Africa is ?a thing of the past?.

Ninja and Yolandi?s then-six-year-old daughter, Sixteen, wearing blackface in the music video for ?I Fink You Freeky?.

Ninja and Yolandi?s then-six-year-old daughter, Sixteen, wearing blackface in the music video for ?I Fink You Freeky?.

Beyond an apparent unwillingness to acknowledge their contribution to modern-day South African racism (or apparently its existence at all), other questionable behaviors have surfaced throughout the decade-and-a-half that Ninja and Yolandi have collaborated. The pair have been accused of grooming a small group of teenage boys in order to steal art used to create the Die Antwoord aesthetic theme, supplying them with alcohol and weed and coaxing them into signing contracts. While none of these practices directly relate to allegations of sexual assault, they are important examples of the lack of social accountability by which Die Antwoord have used their celebrity and privilege.

Ninja?s attitudes toward women and sexuality have ranged from bizarre to outright misogynistic over the years. His unconventional philosophies concerning ?semen retention?, and the male energy that not ejaculating can yield, have been well-documented since The Ziggurat by The Constructus Corporation was released. Fans of the group have noted Ninja?s tendency to interrupt Yolandi in interviews, and of the sparse availability of interviews in which Yolandi receives equal time or attention. One quote from an Eswatini-based music journalist, who had lived in South Africa for several years, on Ninja?s predatory behavior:

? Watkin Tudor Jones is not only a real jerk, he?s a full-on hostile sexual predator who thinks he can get away with it because he?s ?famous? and ?in character?.

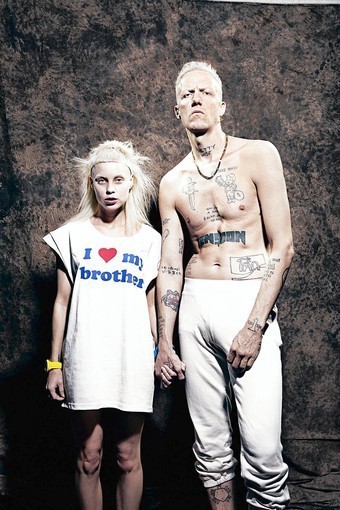

Twenty-five-year-old Australian artist and musician Zheani Sparkes.

Twenty-five-year-old Australian artist and musician Zheani Sparkes.

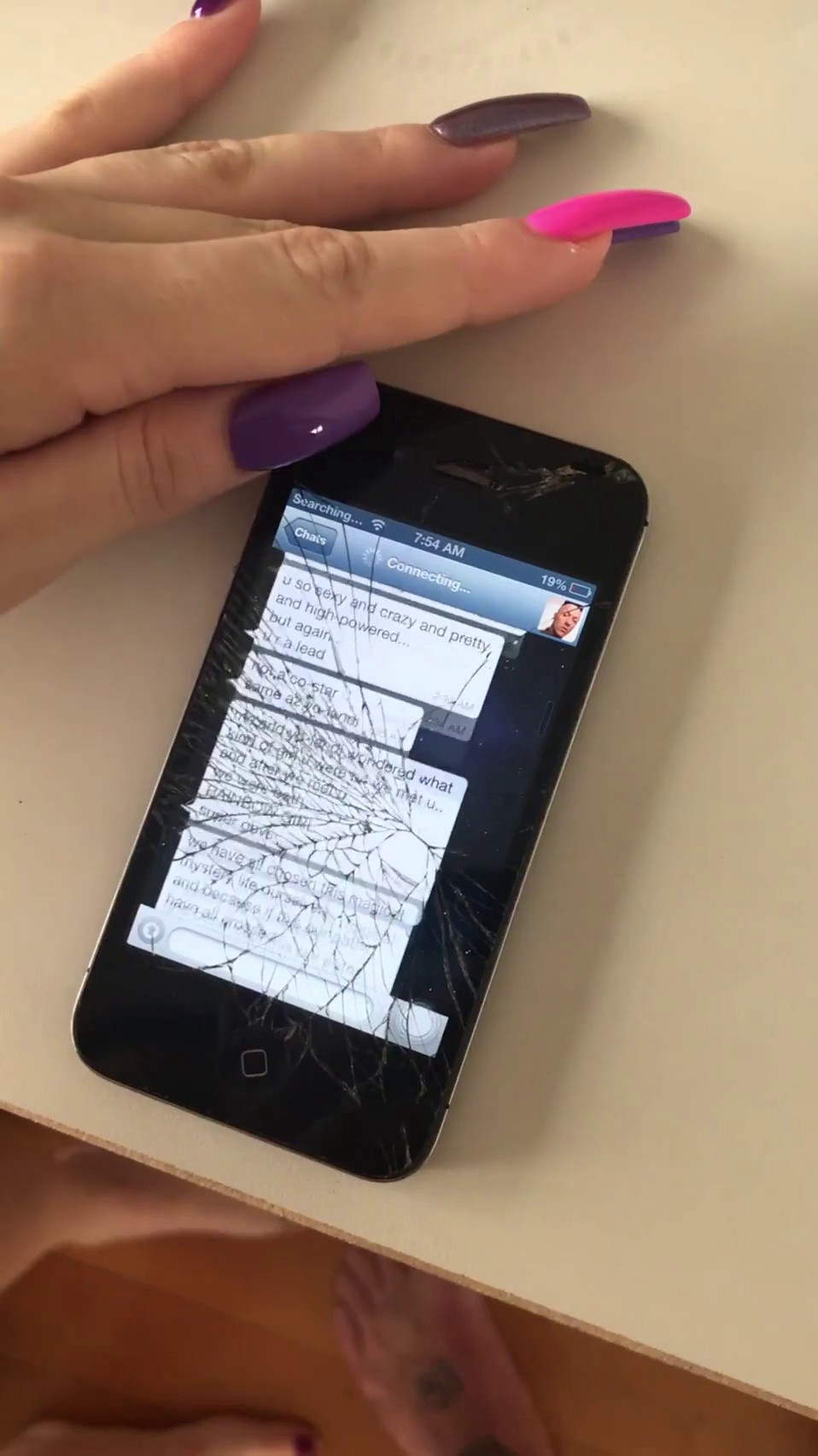

On March 7th, Australian musician, model, and artist Zheani released her new ep, The Line. The album is reminiscent of the empowered post-Crystal Castles sound that Alice Glass has found over the last few years in her solo career. I say this for two reasons: musical, and personal. The final track, ?The Question?, is a very pointed diss track which asserts that Ninja from Die Antwoord expressed interest in her due to her resemblance to his daughter Sixteen, that Yolandi was knowledgeable and complicit in grooming her (and other fans), that he forced her into performing nightmarish sexual rituals, and that she was one of the women in the explicit photos Ninja was allegedly showing women on the set of Chappie.

Ninja is, among other things, being accused of soliciting sex from young women on the basis that they look like his daughter, Sixteen.

Ninja is, among other things, being accused of soliciting sex from young women on the basis that they look like his daughter, Sixteen.

In two Instagram posts entitled ?CLOUT CHASER? parts 1 and 2, Yolandi responded to the allegations. She accuses Zheani of ?clout chasing?: of fabricating a story in order to ride on Die Antwoord?s coattails to promote her new album.

Social media response has been post-#MeToo predictable. The controversy has bifurcated Die Antwoord fans, into those who believe Zheani?s story and those who believe Yolandi?s. Those who believe Yolandi have worn out their share of overused victim-blaming diatribes. If they?re really guilty, then why did she wait nearly six years before bringing these allegations to light? Everyone?s favorite: why didn?t she report this to police, as though going to the police in a foreign country to press charges against an international celebrity is that simple.

After releasing ?The Question?, Zheani has faced a cease-and-desist notice, from which she is not backing down. She has been harassed by countless Die Antwoord fans, either for outright not believing her or just for being mad to pull the veil off of a favorite music group. She has received threats of violence. The Die Antwoord community and music fans at large can, must, be better than this. You can listen to and support your favorite artists without becoming part of an abusive hivemind, harassing someone you?ve never even met.

Those who believe Zheani, however, have in most cases unfortunately not contributed anything any more meaningful to the discussion ? and have reused the same fake-woke platitudes used to unhelpfully support survivors of sexual abuse. Just as Zheani was asked why she hasn?t gone to authorities, Yolandi was asked if they?re really not guilty, then why would she discuss it on Instagram instead of speaking to an attorney for libel, or just staying silent? (The duo have since employed an attorney. This is a denial of guilt on their part.)

Someone who has come forth with a very serious story of trauma deserves more than hashtags about being believed and a social media military. They deserve someone who is willing to try to entirely change the way society identifies and handles sexual trauma. Feeding into the ?did it happen or not?? narrative that so often co-opts sexual assault call-outs, does nothing but perpetuate the same dangerous dynamics that surround every sexual assault case: the potential to invalidate trauma, the fact that two people can leave one experience with completely different psychological responses, and totally overlooking that trauma can be realized at any point in a relationship.

A bigger question asked: why is Yolandi not jumping to support another woman?

Even when partners of people who perpetrate abuse are implicated in that abuse, we must wonder whether or not they themselves are being abused.

I have honestly been secretly wondering for some time now when Ninja will get outed for abuse ? but not by a fan, or a fellow musician, but by Yolandi herself. The optics of their dynamic have seemed very questionable to me. Yolandi, although she has brought just as much to the creative process for all of the projects she?s collaborated with Ninja on, has frequently been relegated to supporting character roles. This was most evident during their MaxNormal.TV days, in which Yolandi ? first assuming this pseudonym ? played MaxNormal?s personal assistant. MaxNormal.TV was also the project the duo worked on shortly after the birth of their daughter, Sixteen: an era in which Yolandi has described herself feeling ?very isolated?.

We must consider the vantage point from which Yolandi is operating. Yes, she is Ninja?s musical partner, co-parent, and a close confidante and friend. However, she is also someone who depends on him financially as a working partner, who has built a life with him (which don?t simply unbuckle like Velcro), and who has the potential to be retaliated against in numerous ways (physical, financial, emotional, familial) should she choose to stop supporting him. This is a situation that many people in dysfunctional relationships find themselves in, and it speaks less to Yolandi?s role as Ninja?s enabler and more to her entanglement with him. We have seen this before with bandmates, romantic partners, and family members of abusive people. Sometimes, the people we are closest to are both most afraid of us, and see the greatest good in us. They are awarded the full spectrum of what we are capable of, both great and terrible.

Part of recovering from abuse means unlearning the abusive behaviors we have adopted in order to survive, while also taking responsibility for perpetuating the very abuse we have been subjected to. The cyclical nature of abuse means that, in an ideal restorative justice setting, many people being confronted for their abusive behavior would have an opportunity to work through trauma of their own. I imagine, without a shadow of a doubt, that this would apply to Yolandi. As Zheani herself sings in ?The Question?, Yolandi through brainwashing may have been subject to her own trauma as well.

I don?t give a fuck you spent a decade with the manGetting brainwashed by this manYou?re still playing out his planAnd grooming up his fucking fans ? ?The Question?, Zheani

Yolandi, in her response to Zheani?s accusations, cautioned women to realize what power we have in situations like these, but it?s hard to find anything meaningfully or logically valid about that statement. At some points, however, abuse might not look like abuse, and instead might look like being a good partner, faithful, or doting. It may look like loyalty to an ideology, religion, or deity. It might look like perpetuating the very abuse that they themselves have been subjected to.

When trauma is happening to us, we may not realize it, because those around us have normalized it. We may never realize it. Admitting to yourself that abuse took place is both the first step toward recovering from abuse, and sometimes the longest and hardest step. Abuse doesn?t have to be immediately realized for it to have taken place.

I was invited to join a sex cult when I was 19. I?m not sure what else to call it, without admonishing the women still in the relationship (if any). A man about fifteen years my senior began a relationship with a friend of mine; he had three other women living with him like wives, whom he referred to as ?the girls?. The four women lived on the second flat of a large three-story home downtown, while the sole man took his place at the top of the castle.

The five of them were involved in a cult similar to Adidam, a small neo-religious movement, a sort of Western appropriation of Hinduism led by a man who, before his death, had been accused of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse by followers. Abusive undertones were prevalent throughout my short-lived friendship with the man. He instructed I call him ?Da?. There was a clear imbalance of power and, in trying to end contact, I was berated, mocked, and my income was threatened, by multiple members of the relationship.

Sound familiar? Abuse propagates itself like a virus, infecting those who are subjected to it and, often, spread by those same victims.

When the animosity reached my best friend, another potential ?wife? for ?Da? to take in, I cut off contact completely. I later left the state. About a year later, his most recent partner contacted me to apologize and explain that she?d left the relationship, that ?Da? had forbidden her from contacting me, that he had become extremely controlling, and that I?d been right. But if there was really abuse, why didn?t she say anything about it before? Perhaps because she lived with him, feared him, and loved him. See how ridiculous this sounds now? I can think of three women who, at the time, were all aged 18 or 19, who were manipulated and hurt by this man in some way. We would probably never be believed now.

And why would anyone believe us? Were they there? Innocent until proven guilty, right?

Emotional trauma can, unfortunately, not be proven. And that shouldn?t be the point of identifying rape. The point is that someone is walking away from a sexual or romantic encounter with trauma: feeling hurt, confused, coerced, ashamed, or upset. Never really feeling the same again.

The vast majority of sexual abuse is perpetrated by those close to us, or acquaintances of ours, and cannot be proven beyond a ?his word against hers? framework. Yet traditionally, we follow a judicial protocol when analyzing sexual assault cases, rather than a psychological or sociological. If it is not overt (read: easily prosecuted in court, with evidence of battery) we don?t recognize it. We follow ?innocent until proven guilty?, for crimes in which guilt is impossible to prove. These policies completely overlook the fact that rape is one crime in which the perpetrator can legitimately believe they?ve done nothing wrong, yet the survivor is left completely traumatized.

This is often magnified by the fact that consent is not black-and-white. In cases where rape is overt ? a weapon is brandished, force is used, the survivor was unconscious or underage, and so on ? the optics are clearer. People are believing less and less that rape is triggered by a woman?s dress, or that it?s a woman?s fault if she?s raped walking by herself in a back alley; more people are beginning to recognize that, surprisingly, men are capable of not forcing themselves sexually. People now identify that men can be raped as well. However, in cases of covert rape, where the optics are not quite as obvious, the guilt and self-admission that weighs on a survivor afterwards can leave them wondering for years whether or not the rape actually took place.

The difference between a covert rape and an overt rape is often whether or not the survivor has stood up for themselves, and when they are retaliated against or outright ignored. This is what stops so many people from saying ?No?, from defending themselves or trying to. There?s the overarching fear: what if I try to stop it and it doesn?t, or it makes it worse? Thus, so many rapes end in one satisfied person and one traumatized one, with the satisfied party sometimes never realizing that what they did was wrong.

Consent is not black-and-white. Most of us aren?t trained in what consent looks like. Consent, seemingly willful, can be given under pressure, out of fear, out of coercion, because somebody is rich or powerful or famous, or we?re scared to hurt them (and what they?ll do ?in defense?), or simply because we don?t know how to say ?No? even when we want to. And, yes, someone can be hurting you and not realize that they are hurting you. What is most important is to help survivors recover from their trauma, and prevent people from traumatizing others in the future.

It is a universal experience among women to be terrified while something is happening, and to lie to ourselves and others about the trauma, in order to protect ourselves both from the trauma itself and from potential backlash from others. This is why we fake orgasms, go on dates with men we?re not interested in, feign interest, and why we reject men carefully. Most women are terrified to reject men, and men give us lots of good reason to be.

The first time I was raped, I was sixteen. I remember hearing him say ?I just want to make you cum? on repeat, while I blurted every lie I could think of why I didn?t want that (including ?you don?t want me, I have herpes?). I remember him slipping a condom on and going for it anyway, as I eventually literally said ?Fuck it, why not?? out loud and, as Barbara Driver may have prescribed, tried to lay back and enjoy it.

Yolandi and Ninja during their MaxNormal.TV ?corporate hip-hop? days. During this time, Yolandi played assistant to Ninja?s MaxNormal, during an era she described feeling ?very isolated?.

Yolandi and Ninja during their MaxNormal.TV ?corporate hip-hop? days. During this time, Yolandi played assistant to Ninja?s MaxNormal, during an era she described feeling ?very isolated?.

For years afterwards, sometimes, sex would end for me in complete dissociation or fits of crying. The most traumatic part was that, as Mary Gaitskill wrote in 1994 of a similar situation, I felt as though I had raped myself, by not standing up for myself better. I don?t need anyone to say ?I believe you?, nor am I upset by those who would suspect I am lying. I know it hurt, and I don?t care whether or not you believe me. I want to do just one thing: I want to find the man who did this to me, and explain to him the hurt he caused me, and how it happened.

Research suggests that mediated conferencing between survivors and their assailants can increase empathy by assailants as well as reduce PTSD symptoms in survivors. As a restorative justice advocate, this is what my justice would look like. Not incarcerating him and perpetuating the broken systems that keep powerful men powerful and poor men in jail. It would look like actually preventing him from ever hurting anyone else again, and preventing others from doing the same. It would look like changing the conversation around sexual trauma.

But the person who raped me was an unemployed skateboarder who lived with his parents: not exactly a ?powerful? man. How do we prevent people in power from hurting us? Can we, even? Both I and Zheani went years without speaking publicly of trauma. My story is not hers, but I would guess that she probably stayed silent for all the reasons I just outlined, with one more big one: Die Antwoord are international celebrities.

As long as power disparities and imbalances exist, there will always be a risk of trauma. Always. The harm reduction comes from each of us understanding the power we have over each other and doing everything we can to use it to help others. Particularly men. Particularly older people. And, particularly, the wealthy, famous, and celebrated.

This brings me to Ninja. Back to Ninja. The man of the hour.

Ninja?s privileges are vast and obvious. He is a well-educated white man in post-apartheid South Africa. He has a net worth into the millions of dollars. He is internationally recognized and celebrated, and has access to top-notch attorneys and public relations managers to command. Zheani is a musician and artist and semi-well-known in an Internet kind of way. Looking at power from all angles ? industry power, institutional power, economic power, political power ? Ninja clearly has the upper hand, and greater capability to escape responsibility from wrongdoing.

Obviously: powerful people understand, clearly, that they are powerful ? then they use that power to obfuscate taking responsibility for wrongdoing. We glorify this behavior, nominate and elect these people for public office, and celebrate people in power using power as a vantage point for self-interest. Why are we celebrating this? We need to stop that!

Here?s an idea: what if most of us are completely dissatisfied with our lives, because we feel we have little choice or say in the way things go for us? We settle on a job, a partner, and a home, because our options are limited to us. We prop up an elite class of people who have more choices, and less responsibility, because we someday long to join their ranks. We ignore the fact that the very existence of that elite class is why we have so few choices in life ourselves. Power hurts people, perhaps in ways we don?t intend for as individuals. Most of us are not sociopaths, yet we are all vulnerable to possibly abusing our power for self-interest, without regard for those we hurt along the way. And our societies celebrate when people abuse that power.

Consider the car. Cars kill people. They do. Constantly! Yet we acknowledge and appreciate their necessity in society, and how efficient they make things and, indeed, how enjoyable they can be. Thus, we make them safer. We?ve mandated safety belts and airbags. We?ve invented breathalyzers for people who?ve been caught drinking and driving. We respect the car?s ability to kill us, and require training for potential drivers, and enforce punishments for when we?re caught driving dangerously. We seize licenses from people determined to drive badly, and do everything we can to ensure that those who do drive, do so safely.

We respect that, in our cars, we can hurt people badly without meaning to ? and so we are instructed to pull over during auto accidents, and make sure that all the people and property involved are cared for appropriately. Impact before intention. Yet, when we are hurt psychologically by people in positions of power, they are instructed to protect that power more than anything else. Their reputations become more valuable than other human beings.

Power hurts people. Privilege hurts people. Why aren?t we respecting that? What if, following car accidents, we were instructed to just keep driving? What if we celebrated car crashes the exact same way we celebrate powerful men abusing and fucking up our society? (Just look at NASCAR.)

Why don?t we, instead, create a social framework that reduces the chances of people in power and of privilege hurting us?

When we are not all created equal in society, wrongdoing has already taken place. We need to institutionalize protective measures in order to ensure that this does not end in trauma, as it already has for so many of us.

This should begin in childhood, and into adolescence in comprehensive sexual education. We must explain to young people ? boys in particular ? that people may feel pressured to sleep with others based on their social status, to make them happy, or because we?re scared they?ll hurt us, and that this leads to significant psychological trauma. We must remind them time and time again that there is only one reason to sleep with someone: because you actively, genuinely, and passionately want to.

In cases where someone has abused their power in order to fulfill a personal set of sexual fantasies, we must not glorify this behavior, assume survivors are lying, or dismiss it as simply what happens when a young woman meets a celebrity. What Zheani has described isn?t just something that happens to starstruck women meeting celebrities, but it happens on college campuses by athletes, spouses financially dependent on family breadwinners, in families between relatives, and by seemingly everyone who?s ever met many Presidents of the United States. Soon there will be an even bigger stigma against people who use institutional power for sexual self-interest, than the current stigma against those who dare hold the powerful accountable for treating others properly. Starting now, we need to be prepared to change what it means to have power.

Zheani Sparkes is an artist, musician, and activist, who spent eight days of her life in South Africa with one of the most famous rave groups in history and then didn?t speak of it for years. We need to support her right now as she defends not only herself, but other survivors and, ultimately, other people who could be victimized in the future. The best way to do this is by opening a discussion on abuse prevention and power imbalance.

One silver lining for every survivor can be having that opportunity.

(Note: this article previously incorrectly described Karl Muller as a South African music journalist. It has been corrected to reflect Muller?s nationality.)