Bloody Hell

The Mystical, Magical Properties of Period Blood

How one fairly innocuous fluid became so central to so many myths

Photo: Alan Dyer for VW Pics / UIG / Getty Images

Listen to this story

–:–

–:–

Though periods are a fact of life for tens of millions of humans around the globe, the reality of a period ? that for several days, multiple times each year, a person bleeds somewhat consistently ? is often obscured by the ethos around them. We talk about PMS, ?that time of the month,? cramps, syncing, and even period pain somewhat freely ? but the actual byproducts of a menstrual cycle remain unspoken, unexamined, and generally ignored or stashed away.

The Western world?s discomfort with menstrual blood is evident in its relative absence from just about every aspect of life. Euphemisms abound, soiled items are mummified and hidden in the bottom of wastepaper baskets, and, until very recently, advertisements for hygienic products whose sole purpose is the staunching of blood never feature images of it or even speak its name.

However, this isn?t universally so and certainly hasn?t always been the case.

Though there is a persistent and widespread legacy of negative associations with periods and period blood ? anthropologist Beverly Strassmenn called it ?almost a cultural universal? ? there are the few outliers who have viewed and still do view menstruation, and its products, as positive and powerful.

In these cultures, the period?s cyclical appearance has long been linked to the waxing and waning of the moon, and its relation to fecundity and childbirth often lent it additional gravitas. Period blood, then, has at times been viewed not as excessively unclean, but instead as containing extreme potency.

![]()

Egyptians, Native American tribes (including the Nootka and the Navajo), and Eastern Asian cultures all engaged in ceremonial events around menstruation, primarily the first period. However, few kept the blood for any kind of use.

According to the Museum of Menstruation, at least a few groups of early humans did so.

The Mesopotamian mother goddess Ninhursag was said to make men out of loam and her ?blood of life.? She taught women to make loam dolls for use in a conception spell by painting them with their menstrual blood.

Though the vast majority of recorded menstrual beliefs are not good.

Despite copious period taboos that persist throughout history, from the Old Testament to modern-day snipes about ?blood coming out of her wherever,? there are instances in the anthropological record demonstrating that although periods haven?t necessarily been beloved, their power has been revered.

In Blood Magic: The Anthropology of Menstruation, editors Thomas Buckley and Alma Gottleib explain that while the vast majority of documentation around menstrual mythology is negative, a handful of ?ritualistic? uses for menstrual blood are positive ? including but not limited to ?the manufacture of various kinds of love charms and potions.?

Love potions are one of the more frequent uses for menstrual blood in folk mythology (including hoodoo), though it seems the retelling of some of these tales is more to disparage individuals and cultures viewed as below the status of white, Western doctors. One snippet from the 1894 Cincinnati Lancet contains a particularly offensive and telling anecdote about a ?dark-colored damsel? who wished to ensnare a man by mixing menstrual blood into his coffee. The author notes that while they?d seen some ?very peculiar ideas? from people of color about love potions in the past, this particular instance was ?entirely new,? expressing a next-level kind of bemusement.

Buckley and Gottleib also note that the negative connotations around period blood were, at times, employed in the pursuit of positive outcomes. Because it was viewed as toxic or dangerous, menstrual blood might be utilized to ward off evil or protect land or livestock.

?We suspect,? the authors write, ?that such a dialectical relationship between the positive and the negative poles of symbolic menstrual power is found more commonly than has been remarked upon.?

Indeed, earlier texts note that the dreadful power of menstrual blood meant that it had been put to work in areas where only really strong stuff would do.

An excerpt from ?Menstruation and Its Disorders,? 1922.

An excerpt from ?Menstruation and Its Disorders,? 1922.

?From the belief that menstrual blood is very poisonous,? wrote Emil Novak in Menstruation and Its Disorders, published in 1922, ?it was?only a short step from the supposition that it might exert a powerful influence against sickness.?

Novak explained that Roman philosopher Pliny recommended menstrual blood for illnesses such as gout and worms.

Pliny had many thoughts about menstruation. In his Natural History, he described it as ?noxious? and wrote that it could make dogs go insane and wine turn bad.

Pliny was willing to concede, however, that it could potentially be used for good.

Many writers say that, baneful as it is, there are certain remedial properties in this fluid; that it is a good plan, for instance, to use it as a topical application for gout, and that women, while menstruating, can give relief by touching scrofulous sores and imposthumes of the parotid glands, inflamed tumours, erysipelas, boils, and defluxions of the eyes. According to Las and Salpe, the bite of a mad (log, as well as tertian or quartan fevers, may be cured by putting some menstruous blood in the wool of a black ram and enclosing it in a silver bracelet; and we learn from Diotimus of Thebes that the smallest portion will suffice of any kind of cloth that has been stained therewith, a thread even, if inserted and worn in a bracelet.

Additionally, Pliny wrote that it was ?universally agreed? that a person who had been infected with rabies ? someone who had ?been bitten by a dog and manifests a dread of water and of all kinds of drink? ? could also be cured by wearing a strip of cloth dipped in ?this fluid.?

In later medical treatments, according to Novak, the blood was not worn in a bracelet or clipped to a person, but was instead ?extracted from cloths by means of Rhein wine or vinegar? and applied directly to sores and cuts.

![]()

Who?s Afraid of the Big, Bad Blood?

This tension between reverence for its power and squeamishness surrounding its existence has guided the view of menstrual blood for centuries. And while some groups attempted to harness the power of the period, the Western world was not quite so open-minded.

As humans began to better understand the inner workings of the body ? and what causes disease ? menstrual blood was no longer a necessary component of cures for goiters and skin conditions. Instead, it retreated to being simply a mysterious (and still somewhat scary) aspect of being female. To some, this was a good thing.

In National Healths: Gender, Sexuality, and Health in a Cross-Cultural Context, authors Michael Worton and Wilson Tagoe describe physicians like Thomas Raynold, who first published his defense of menstruation in 1540. Raynold reasoned that menstrual blood couldn?t possibly be toxic if it was also integral to the process of childbirth.

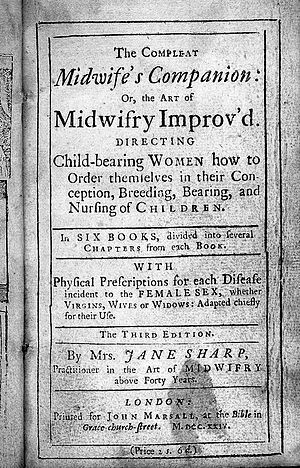

Jane Sharp?s ?Midwife?s Companion: Or, the Art of Midwifry Improv?d, Directing Child-bearing Women how to Order themselves in their Conception, Breeding, Bearing, and Nursing of CHILDREN.?

Jane Sharp?s ?Midwife?s Companion: Or, the Art of Midwifry Improv?d, Directing Child-bearing Women how to Order themselves in their Conception, Breeding, Bearing, and Nursing of CHILDREN.?

Indeed, plenty of doctors knew there must be something positive about periods, even if they didn?t ascribe to witchcraft or other alternative medicines. However, as Worton and Tagoe point out, with the exception of Jane Sharp, one well-known and published midwife, ?women were virtually silent in print? about the reality of their periods.

As such, periods remained somewhat murky, the subject of whispers and ideas and experimentation. People knew they were important but couldn?t quite decide how or what they meant.

In the 1850s, gynecology began to become a much more popular area of medical research and treatment, spreading from the sole purview of the wealthy to a service within reach of the middle class. At this time, menstrual blood was no longer viewed as somehow powerful or useful. However, it was still fascinating, albeit gross, according to many medical professionals.

Menstrual blood was still intimately tied to the historic view that it was somehow different from other kinds of blood. This is in large part because of its regular and predictable appearance, as well as its undeniable link to the place where babies are made. Additionally, because it was almost entirely women who menstruated, menses could easily be associated with every other kind of stereotype or generalization to be made about the gender.

In her 2006 article, ?Menstrual Fictions: Languages of Medicine and Menstruation, c. 1850?1930,? Julie-Marie Strange wrote that ?the idealisation of woman as procreator pervades the language of menstruation,? explaining that ?the very creation of a menstrual knowledge which was inextricable from notions of gender located gynaecology in the realm of fiction rather than fact.?

This link has, in recent years, been extricated some, as the organs of reproduction have been teased away from the construct of gender. But in her writing, Strange clarifies the way in which womanliness and menstruation were viewed as unshakably linked for many, many years:

Despite the scientific rationale that a regular and healthy menstrual flow would stimulate anatomical organs and enhance ?personal loveliness?, physicians persisted in referring to menstruation as an unfortunate, unpleasant and distasteful subject to address and certainly one from which women themselves should be spared.

This negativity toward menstruation isn?t necessarily directed at the blood itself, but instead what the blood symbolizes ? just as it has been, more or less, for centuries.

![]()

Modern-Day Magic

In recent years, efforts to keep the bloody reality of menstruation concealed have been met with unprecedented candor. Companies like Thinkx have taken a different advertising track, actively using words like ?blood? and ?period? ? surprisingly revolutionary acts, all things considered. Additionally, sex-ed classes and literature have become more straightforward and scientifically based in recent years, creating less room for mystery and misinformation. The fight to end period-shaming has been waged with visible bloodstains and free-bleeding, a movement designed to expose, rather than conceal, menstruation.

Even so, menstruation remains the source of stories, as well as experimentation.

For example, menstrual blood as an ingredient in conjuring spirits and making appeals to the otherworldly has recently seen a resurgence ? the use of period blood, it seems, has been heartily reclaimed by those practicing alternative medicines and religious practices.

It’s a tampon in a teacup.

Ghost World (2001) – Yarn is the best way to find video clips by quote. Find the exact moment in a TV show, movie, or?

getyarn.io

A quick Google search of ?period blood uses? will get you no shortage of links to blog posts about using menstrual byproducts to cast spells. The purposes of these spells include empowering objects, increasing fertility, and, of course, attracting a mate. Some spells require simply saving the blood or drawing with it, while others involve drying it and, yes, even consuming it.

There is an inherent danger to using menstrual blood in spells ? though it?s certainly not ?noxious,? as Pliny thought, it is an organic matter and, as a result, contains bacteria that could be dangerous.

Additionally, period blood can transmit diseases just like many other bodily fluids, which means interacting with it (and, certainly, ingesting it) should be regarded with caution. That said, for the most part, period blood is as safe as any other blood, and using it do things like to fertilize plants should be just fine, although perhaps not as effective as using compost.

This reclaiming of the magical properties of menstrual blood is, in many ways, a sign of the times.

Menstrual blood has long been at the heart of mythology and magical beliefs, but it has also been the source of oppression and antagonism; the condemnation of period-havers is rampant throughout much of human history. By grabbing back the power of the period ? the power to control it, to speak its name, and even to put it to use ? menstruating humans are asserting themselves over both nature and a legacy of shame and othering.

659

2

- Women

- Menstruation

- History

- Health

- Womens Health

659claps

659claps

2 responses

Living Where Death Isn?t Tragic

Dave Smurthwaite in MindTrip

Jennifer Crystal: Student Journalist, Survivor

Lissa Harris

Why Bey and Jay Needed To Release Those Bedroom Shots

Ezinne Ukoha

White Fragility at SIEGE

James T. Cutler

A Brief History of the Prison Bae

Elizabeth Greenwood

The Allure of ?Acquanetta?

Ryan Leeds

Life in the 21st Century: The Rise and Fall of a Football Team and a Shopping Mall in Knoxville, TN

Hollis Oliver McLain III in Smoky Mountain Source