In 2016, while listening to Spotify, I heard an ad from Barack Obama. I can?t remember it verbatim, but it was something like: ?when I hear people say your vote doesn?t count, I get fired up.?

It?s a carefully chosen phrase. Your vote absolutely counts, but it doesn?t matter. Yes, you?ll change the total number of people who voted for one candidate, but you won?t change the outcome.

I Know What You?re Thinking

Okay, time to talk about objections. We?ll start with the most common one. ?If everybody thought that way?? But everyone doesn?t think that way. Hardly anyone thinks that way. More importantly, if you decide to start thinking that way, the entire world won?t automatically follow you. This isn?t very hard to get in contexts where people aren?t emotionally involved. For example, suppose you?re a doctor. If everybody decided they wanted to be a doctor, competition for doctor jobs would be even more insane than it is now, and no other job in society would be filled. It?d be horrible. But it?s absurd to think of that possibility when choosing an occupation. Nobody ever worries that their decision to become a doctor will magically translate into the rest of society enrolling in medical school. Somehow, though, people always seem to get stuck on the voting thing.

A related objection to the first is that you may effectively have more than one vote if you can change your friends? minds. This argument is similarly weak: one reason is that you just don?t have that many friends. I?m not being sarcastic, I?m just saying most people aren?t in a position to influence very many people. To make a difference in a presidential election, you need to influence lots of people. A second reason this argument is not compelling is because it?s super hard to change people?s minds. For a meta example, if you are a die-hard believer in voting, there is almost no chance I?ll be able to change your mind by the end of this essay. I?m resigned to that. (So why write this? More later.) For an even clearer example, suppose I try to change your mind about abortion. Do you think I could do it? I doubt it. Even with excellent reasoning, it would probably end up like the comments section when the New York Times publishes a conservative editorial. (That is to say, completely entrenched parties on both sides attacking one another?s moral character and intelligence.)

So don?t worry that if you decide not to vote everybody will follow along. It won?t happen. No way. Not a chance.

The next objection is to bring up some example where an election got really close. The problem is, they aren?t really elections that matter much. House of Representatives elections have come down to a single vote in the past. (Two times in Nevada, they settled exact ties with a coin flip.) It?s never happened with a presidential election, even the famous Bush vs. Gore election came down to several hundred votes.

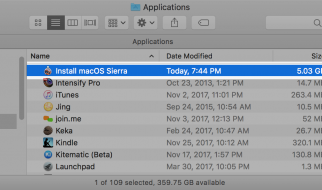

Even if it is super close, we can see what happens: counting errors make more of a difference than individual votes. Recounts in 2000 swung the vote count by hundreds of votes, not by handfulls. (From 1278 to 900 to 537). When the election really matters, recounts will happen.

Now suppose we had perfect vote counting systems, with zero measurement error, and the election comes down to a single vote. Now, surely, your vote matters, right? Well, which one of the millions of votes on the winning side gets credit for the win? Every single person cast a vote, so the credit perhaps should be shared across all of the millions of voters. People hate this argument, and the common response is to point out that the absence of any single vote would have changed the outcome. That?s not actually true with certainty, it?d take two votes to make sure. Starting from a 1-vote win for Candidate A, removing a single vote for A leads to a tie. If you don?t show up to vote for A, and the tie break chooses A, your vote wouldn?t have mattered. So even without counting errors, there?s still some ambiguity about the value of exactly one vote, which rests on how ties are broken.

The Expected Utility Argument

Finally, we have an objection that is founded on expected utility theory. This idea is as follows: the chance that you make a difference is tiny, but the potential payoff is so big that it outweighs the low likelihood. A quote from the best argued article I?ve read on this:

The impact of your vote largely depends on 2 things, which we?ll investigate in turn:

1. The chances of your vote changing the election outcome.

2. How much better for the world as a whole one candidate is, compared to another.

At first blush it might seem that the chances of your single vote changing the election outcome are zero. But while the chances are low, they could be around 1 in 10 million if you live in a swing state.

And that small chance matters, because who runs the US is kind of a big deal.

Embedded in this reasoning are several assumptions, some of which are extremely sticky. Much worse are the hard figures the article puts to the different variables.

The first problem is in determining ?how much better for the world as a whole one candidate is, compared to another.? You must believe in something called interpersonal utility comparison for such a statement to make sense. We need to be able to add up all the positives and negatives of one president and then sum them across people. In other words, I need to reduce Candidate A?s impact to a set of positive and negative numbers. Then, those numbers have to mean the same thing to different people. I need to do that for everyone who will be influenced by Candidate A. That includes a whole bunch of people who might not be born yet.

The second problem is that, even if there is some true societal benefit to one candidate over another, the article assumed you can estimate it perfectly. That?s totally circular though, otherwise why even have a vote? If everybody knows candidate X is better for society, we?re done. There is a subtle but pernicious form of hubris in the article, which derives from ignoring that fact that you could vote for the wrong person. No, of course, you?re too smart for that, and you?re always right about every decision you make, and you can perfectly judge which candidate will be better for society in the long run, and you can figure it out precisely enough to conclude it?s worth going to the polls for. The article goes even further and concludes

the single hour you spend voting for the President and Congress can be the most important thing you do with an hour each four years

Sure, but it might be important in the wrong direction.

Another tricky point comes from the theory/practice gap. The article reasons from expected utility theory. Expected utility theory is useful. I use it in my research. But we all know it?s an abstraction, something with major problems (At least two Nobel Prizes in economics have been awarded for research partially showing expected utility theory is unrealistic.) In short, if the problems with it are small enough relative to the information gains, fine, use it. I don?t believe that?s true here, because voting is an edge case. You need absolute precision in edge cases like these. Expected utility doesn?t cut it.

One of the main weaknesses to point out briefly is that a blind adherence to expected utility lead to lots of decisions most people deem ridiculous. Expected utility theory trades off probability with outcome value. Really unlikely things are made more important if they have large consequences. For example, Earth could get nailed by an asteroid and it would be really, really, really bad. Expected utility theory says that asteroid hunting should be pretty high on our list of things to do. There could be another financial crash any day. There is a tiny chance that someone could figure out how to launch an unauthorized nuclear attack and start WWIII. Malevolent super-intelligence, runaway global warming, pandemics, hostile extraterrestrials, the list goes on. But here you are, not worrying about that stuff. Why not? Because you probably don?t live your life by expected utility theory.

If I were to supply a replacement for expected utility theory most suitable for the voting question, I?d use the Kelly Criterion. It is a way of calculating how much you should spend on a particular activity, given the probabilities and payoffs involved. The key is that it was developed for extremely unlikely events (like your vote changing an election outcome.) The Kelly Criterion is like expected utility, but it is more sensitive to the chances of ?going broke.? In this context, ?going broke? is voting every single election in your life and never changing the outcome. Since this will almost certainly happen, the Kelly Criterion is more likely to say voting isn?t worth the effort. So even if you have all the figures perfectly estimated, it is unlikely to be worth voting if you use the Kelly Criterion instead of expected utility theory. The Kelly Criterion is far more applicable and realistic, in my view.

Why People Really Vote

Direct benefits. For most, this comes from a feeling of satisfying civic duty, which is fine. Another reason is the process of engaging in politics makes you feel valuable to those around you. All good.

Why did I write this essay? For similar reasons. Getting my thoughts down is an extremely satisfying process. Some people will read it and I?m glad when that happens, even if I don?t change any minds. It?s pretty selfish, I admit, but at least I?m transparent. Others will tell you they?re making a difference but they almost never are.

Speaking of which, I hinted that there are a few exceptions to some of the above arguments. Notably, the candidates for president. They have serious influence on the election outcomes. People like that are on what I call ?The Short List.? Does that suggest that you should just try to get onto The Short List? I don?t think so. Getting onto The Short List is like changing an election with your vote, it?s just super unlikely. Most of my arguments above apply. I suspect most people get onto The Short List unintentionally.

I will reveal that I actually vote, even though I don?t believe my vote will matter. I get direct value from voting, regardless of the outcome. This direct benefit vs. aggregate impact framework has been a useful guide for me in making certain decisions in my life. Reduce your carbon footprint? Not worth it. It?s just like voting. Pick up that piece of litter in the hallway? Totally worth it, to me. A cleaner hallway provides value to me and dozens of other people walking around. That is a great payoff for the effort of stooping down. More importantly, whether or not it provides value doesn?t hinge on the actions of millions of other people.

I hope, if you?ve made it here, that you don?t take this for cynicism. I find it optimistic, myself. It lets the air out of the issue, it?s freeing, and it is a way for me to recognize my place in society. If the same isn?t true for you, I take comfort in the fact that I probably didn?t convince you anyway : )