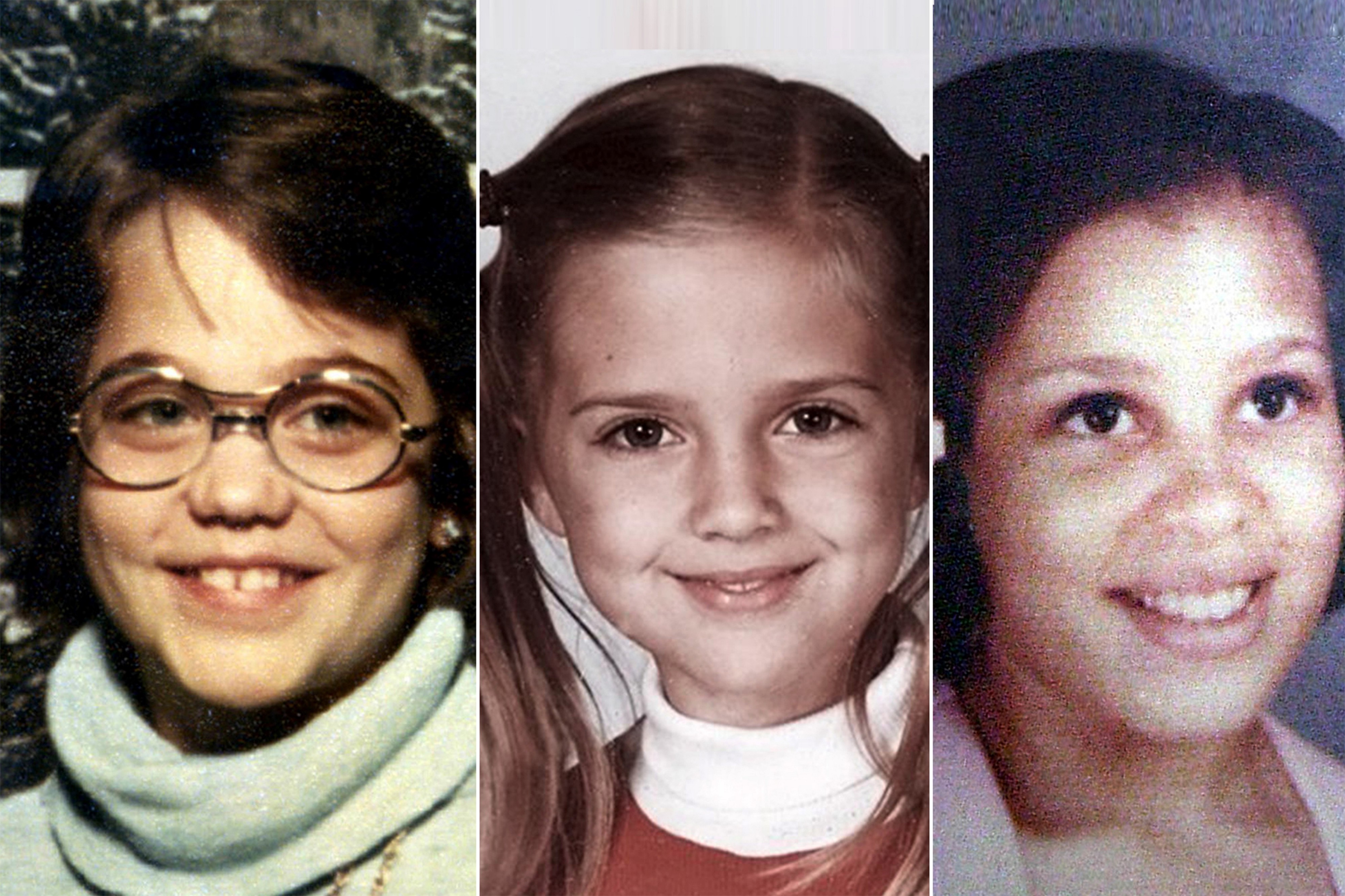

On June 13, 1977, Michele Guse, Lori Farmer, and Denise Milner, were all brutally murdered while at Camp Scott, outside of Tulsa, Oklahoma.

On June 13, 1977, Michele Guse, Lori Farmer, and Denise Milner, were all brutally murdered while at Camp Scott, outside of Tulsa, Oklahoma.

40 years ago, under the extreme darkness of a waning crescent moon, three Girl Scouts were brutally murdered at Camp Scott, in Oklahoma.

June 13, 1977, marks one of the most terrible and shocking crimes in Oklahoma history, kicking off an investigation that continues to this day.

The now-abandoned Camp Scott is in a densely wooded location on 410 acres in Mayes County, Oklahoma.

The now-abandoned Camp Scott is in a densely wooded location on 410 acres in Mayes County, Oklahoma.

Girl Scout Camp

Anticipating two weeks of activities and fun, Lori Farmer, 8, Michele Guse, 9, and Denise Milner, 10, were heading to their Girl Scout Camp near Locust Grove, northeast of Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Located just two miles from town in Mayes County, Camp Scott had been operated by the Girl Scouts since 1928. Generations of girls had gone there for the annual two-week getaway.

Michelle Hoffman has never forgotten her first time at Camp Scott when she was 9 years old. The first thing she recalled was it was ?dark? there. ?If you?ve never been camping in a platform tent in the deep woods, it?s a little intimidating,? she told Tulsa World.

However, during daylight, Camp Scott was a beautiful campground and a step away from the hustle and bustle of Tulsa. Hoffman loved it there. She hiked, swam and slept in tents, coming back every year.

On Sunday, June 12, Hoffman arrived at the Tulsa Girl Scout headquarters and remembers the parking lot packed with excited little girls waiting to board their buses to Camp Scott.

She recalls seeing Denise Milner, one of the few African American girls? going on the trip, and she could tell she was nervous. Thinking she could provide some encouragement, Hoffman walked over to Denise and her mother, Bettye Milner, and introduced herself.

?Denise was feeling homesick,? Bettye told Hoffman. ?She wasn?t wanting to go to the camp.?

?Why don?t you come with me?? Hoffman offered. ?We?ll ride down together.?

Denise reluctantly went along, and the girls boarded the bus. They sang camp songs all the way to Cookie Trail.

Cookie Trail Road that was traveled by Girl Scout buses to take the girls to camp in 1977. Photo courtesy of Tulsa World.

Cookie Trail Road that was traveled by Girl Scout buses to take the girls to camp in 1977. Photo courtesy of Tulsa World.

Occupying 410 acres, with a creek running through Camp Scott, is surrounded by densely wooded forest.

The units, all named after Native American tribes, consisted of several campers? tents and a counselors? camper tent. The tents sat on wooden platforms and held 4 cots for sleeping while all four canvas sides rolled up.

Hoffman described arriving at Camp Scott as always, a sort of ?stepping off.?

As you turn off Oklahoma 82 onto Cookie Trail ? the road narrows to the camp entrance ? and as you turned onto the dirt road, the wilderness suddenly comes alive with color. A peaceful place, and a place where children were safe ? until that night in 1977.

That year, Hoffman had hoped to become a camp counselor, so she escorted Denise to her tent. It was Kiowa Tent ?8; a tent Hoffman had stayed in many times.

Carla Wilhite recalls meeting Denise and recalls her as a beautiful and radiant child. ?She was the only African American and a first-time camper, and I remember thinking we would want to make sure she had a good start and a great experience,? recalled Wilhite.

Denise was introduced to her tent mates Lori and Michele, and though they didn?t know each other, they seemed to bond quickly.

Hoffman came back later to say goodnight to the girls, and all were off to sleep looking forward to the fun that would come the next day. However, that night there was an early evening thunderstorm making it especially darker than usual.

One girl, Amy Sullivan, recalls writing in her diary that evening by flashlight.

?It was the darkest dark I had ever known,? she said. Though enchanting, it was a little bit scary at the same time for her. ?I couldn?t tell if my eyes were open or shut.?

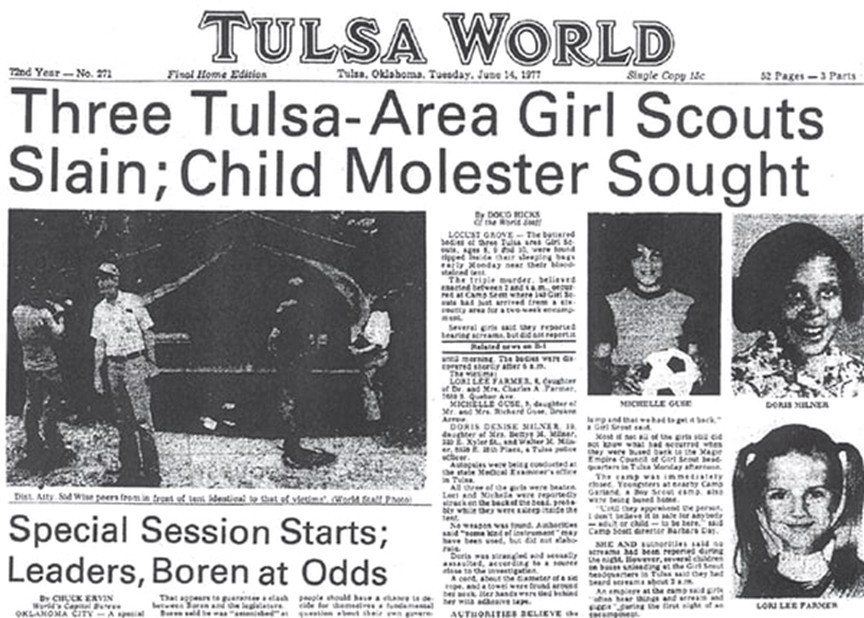

The June 14, 1977, edition of Tulsa World Newspaper with the Girl Scout Murders on the front page.

The June 14, 1977, edition of Tulsa World Newspaper with the Girl Scout Murders on the front page.

The Murders

The following day the news broke. Three Girl Scouts were found slain at Camp Scott near Locust Grove. The shocking headlines were seen throughout Oklahoma.

Parents hearing the news were horrified.

June 14, 1977, parents were horrified to hear there were three brutal murders of Girl Scouts at Camp Scott outside of Tulsa.

June 14, 1977, parents were horrified to hear there were three brutal murders of Girl Scouts at Camp Scott outside of Tulsa.

All three girls had been beaten and strangled and left under a tree approximately 100 yards from their tent.

The girls were discovered by counselor Carla Wilhite just after 6:00 a.m. on Monday.

Carla was on her way to take a shower down the trail when she saw the girl?s bodies near the base of a tree. At first, she did not see Lori and Michele because they were zipped inside their sleeping bags.

Denise was lying on top of her sleeping bag. She was obviously deceased when Wilhite saw her. Confused and horrified by what she had seen, she turned and ran for help. She returned with the camp director and nurse. Only then did it sink in and she recalls being filled with ?a terrible fear.?

Autopsies would reveal that Lori and Michele were killed by blunt force trauma to the head; Denise had been beaten but also strangled with a ligature. All had been sexually assaulted. Investigators determined the attacks had taken place inside of the tent and the bodies moved to the tree.

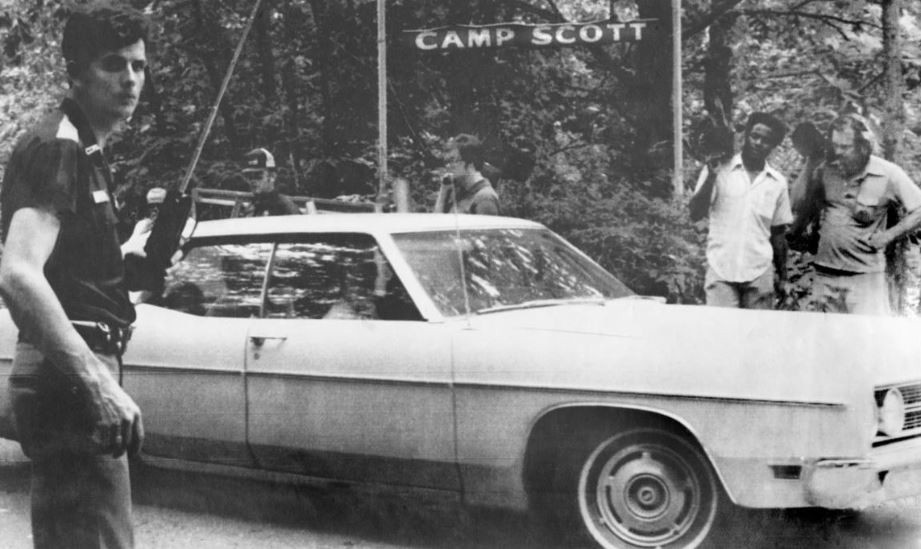

Girl Scouts leaving camp after the triple murder at Camp Scott in 1977.

Girl Scouts leaving camp after the triple murder at Camp Scott in 1977.

The Exodus

Immediately, camp officials began sending the Girl Scouts home on buses and out of the camp where police were now investigating a triple murder.

Sullivan recalls her parents had been in Dallas and her grandmother picked her up that afternoon but remembers not knowing what was happening.

?A few minutes later at a stoplight, I remember looking at her very closely,? Sullivan said. ?I asked her what happened.?

?Oh honey,? her grandmother said with tears in her eyes. ?Three girls were killed at your camp last night.?

The word ?killed? not registering, she responded, ?Killed??

Sullivan wrote in her diary that evening, ?I came home from camp. Three girls got killed . . .?

Sullivan said she later crossed out the word ?killed? and wrote, ?murdered.? She said she didn?t even know what that word meant until that day.

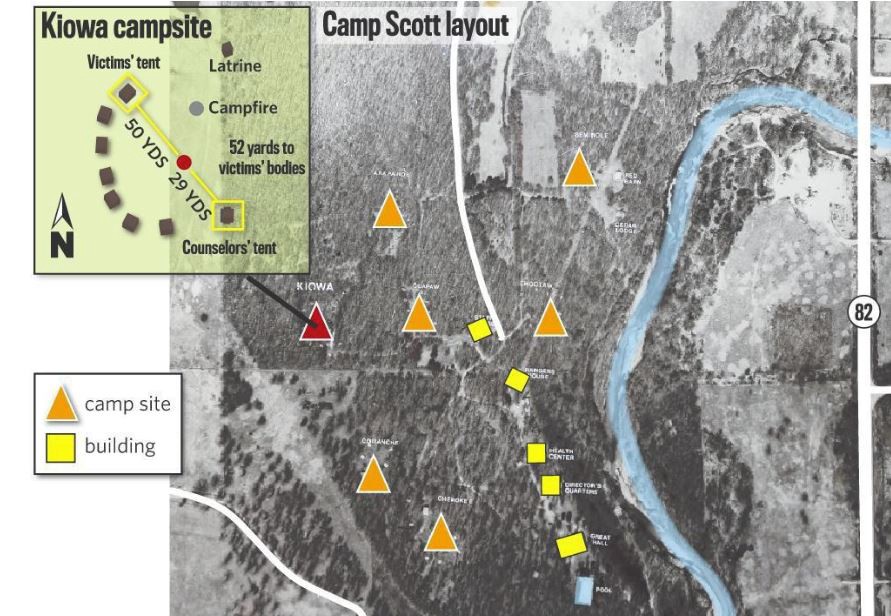

Camp Scott layout where the bodies of three Girl Scouts were found on June 14, 1977, in Oklahoma. Photo courtesy of Tulsa World.

Camp Scott layout where the bodies of three Girl Scouts were found on June 14, 1977, in Oklahoma. Photo courtesy of Tulsa World.

The Manhunt

Dominating the news headlines in the weeks after the murders, police had combed the woods for clues, conducted hundreds of interviews and followed up on dozens of leads.

On June 23, 1977, police named a suspect. His name was Gene Leroy Hart, 33, a convicted burglar and rapist. He was a prison escapee and had been on the run for four years after his second escape from Mayes County Jail.

A native of Locust Grove and a Cherokee Indian, he was now facing three first-degree murder charges.

The DA announced a cave had been found in the area, including items possibly stolen from the camp. Authorities claimed this cave was connected to Hart, who was an expert woodsman and also had many family members living in the area, including his mother.

The largest manhunt in Oklahoma history would begin that day.

Gene Leroy Hart was arrested by OSBI agents at this property in a remote part of the eastern Cherokee County, near Locust Grove on April 6, 1978.

Gene Leroy Hart was arrested by OSBI agents at this property in a remote part of the eastern Cherokee County, near Locust Grove on April 6, 1978.

Finally, on April 6, 1978, the manhunt ended.

Acting on a tip, the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation (OSBI) converged on the home of Sam Pigeon. There, in a rickety old shack, they found and arrested Hart.

Gene Leroy Hart stood trial for the murders of the three Girl Scouts and eventually acquitted.

Gene Leroy Hart stood trial for the murders of the three Girl Scouts and eventually acquitted.

On Trial

The capital murder trial of Gene Leroy Hart would send Oklahoma back to the gruesome day the murders happened. The media was in a frenzy parked outside of the courthouse. The trial would be held in the third-floor courtroom in Pryor, with Judge William J. Whistler presiding.

Leading the defense team was Garvin Isaacs, a former Oklahoma County public defender who now was working in private practice. He had been recommended to the Hart family.

When he first met Hart, he recalls, ?I want you to know one thing: I didn?t kill those Girl Scouts,? said Isaacs. ?Those were the first words out of his mouth. I believed him when he said that.?

Apparently, a growing number of community members and supporters also believed Hart was not guilty.

To raise money for Hart?s defense, a community ?hog fry? dinner was organized, and supporters wore T-shirts that read ?Stop the Mayes County Railroad,? signifying the community?s belief that Hart was being railroaded by police. The Cherokee Tribal Council even donated $12,500 for the defense fund.

21 months after the murders, the trial began.

Glasses were found at the cave near the Girl Scout murders and collected as evidence.

Glasses were found at the cave near the Girl Scout murders and collected as evidence.

The state?s case depended upon two types of evidence. The items that were found at the cave less than 3-miles away from the camp included a pair of glasses, a roll of tape that matched tape found at the crime scene, and some pictures linked to Hart who once worked in a photo lab at the prison.

In addition, biological evidence, including sperm and hair samples, were found on the girls. A footprint was also found in the mud after the thunderstorm the previous evening.

While DNA would not be introduced until the 1980s, and hair evidence had been discredited as a forensic technique, police admitted the evidence they had found was not conclusive proof Hart had committed the crime. Also, there had been no fingerprints.

Quickly, as a defense tactic, the prosecution found themselves on trial. The hair was inconclusive; the footprint did not match the size of Hart?s foot and the evidence found in the cave was not convincing beyond a reasonable doubt. On March 20, 1979, the jurors announced a stunning verdict ? not guilty!

Trying to console the families, the prosecution pointed out that Hart was in no way going free. He was still going to serve over 300 years for previous rape, and burglary charges.

But that was but one piece of horrible news the families would be told. On June 4, Bettye Milner received stunning news. Hart was dead. He had collapsed after exercising and died of a probable heart attack in prison. It was the end ? or so they thought.

The police had no intention of pursuing the case any further for any additional suspects. They had completely focused on Hart and put all their eggs in one basket. In the back of everyone?s mind, they wondered if a killer was still on the loose.

Did a Killer Walk Free?

In early April 1977, when Hoffman was at Camp Scott during a special cadet weekend, someone went into one of her campmate?s tents while they were away. When they returned, they found the tent is total disarray. ?Our bags had been scattered all over the tent and some outside,? said Hoffman.

Whoever had broken into the tent had also emptied a box of doughnuts that Hoffman had brought to camp. Inside she found a note.

?There were four or five pages from a tiny steno notebook,? Hoffman said. On the first two or three pages, written repeatedly, was the word ?kill.?

It was the second message in the notes that would send chills up anyone?s spine. ?We?re on a mission to kill three girls.?

Hoffman said she took the note to the camp director. Later, Hoffman learned several girls had confessed to writing the notes, and the note was thrown away. It had not been brought up by the criminal case but mentioned during the civil case, to prove the Girl Scouts should have been alerted to possible danger prior to the murders.

Questions remained if the girls had written the note, or if they had just caved under pressure of questioning by the camp director.

If the killer did walk free, did they go on to kill other girls?

DNA Advancements

Police had found semen on a pillowcase near the girl?s bodies. In 1989, the FBI tested the sample and were unable to rule out Hart because the tests were inconclusive.

As DNA technology and testing have advanced, police have retested the items found at the crime scene and hoped the killer?s profile will match someone out there. However, in 2008, the FBI retested the semen, but it was too degraded to create a profile.

The FBI?s Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) generates biological evidence that is found at a crime scene. Matches made among profiles in the Forensic Index can link crime scenes together or match possible offenders. Matches made between the Forensic and Offender Indexes provide authorities with the identity of suspected perpetrators. Police labs from across the country upload their profiles to CODIS waiting for a match.

But police need a DNA profile. They are hoping continued advancements will allow them to retest the semen to reveal a long-awaited profile.

Bettye Milner holds a picture of her murdered daughter Denise Milner. Photo courtesy of Tulsa World.

Bettye Milner holds a picture of her murdered daughter Denise Milner. Photo courtesy of Tulsa World.

Living Life After Loss

For over 40 years, Bettye Milner had not returned to her daughter Denise Milner?s grave at Green Acres Cemetery. Bettye told Tulsa World that she had gone to the cemetery but could not bring herself to walk over to the plot located right next to her late husband, Walter Milner. In January 2016, with her friend Majors by her side and after being encouraged by her family ? she finally did it.

?I was glad to be able to finally be able to,? Bettye said.

Her daughter Kristal encouraged her to go to the cemetery, and it was also Kristal?s first time going herself. That day in 1977 she had lost her big sister. Accompanying them was Bettye?s granddaughter Denise, named after the sister Kristal never knew.

Bettye said she doesn?t know when she will go back to the grave again, but it is nice to know she can.

Life can be exceptionally hard after the trauma of losing a child to murder. The loss can sometimes be too much to bear, and families can succumb to the stress, crumbling. But that?s where the three families of the Girl Scouts stand apart. Each continues to thrive.

Bettye Milner says staying faithful to God has helped her deal with the pain and not knowing. ?There is no ?closure.? I don?t know who made up that word. It?s a journey.? Adding no healing will be complete without answers.

Police continue to work the case but sadly, with the Girl Scout Murders ? it has become another day of wait, and just maybe, tomorrow, will be the day the case is solved.

Anyone with information about the Girl Scout murders, please call the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation at 405?848?6724.