Why don?t more translators think it will be helpful to remember in Aeneid 1.203?

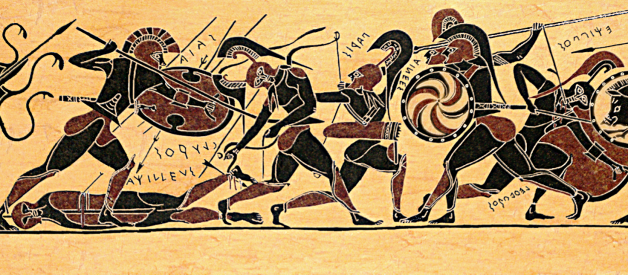

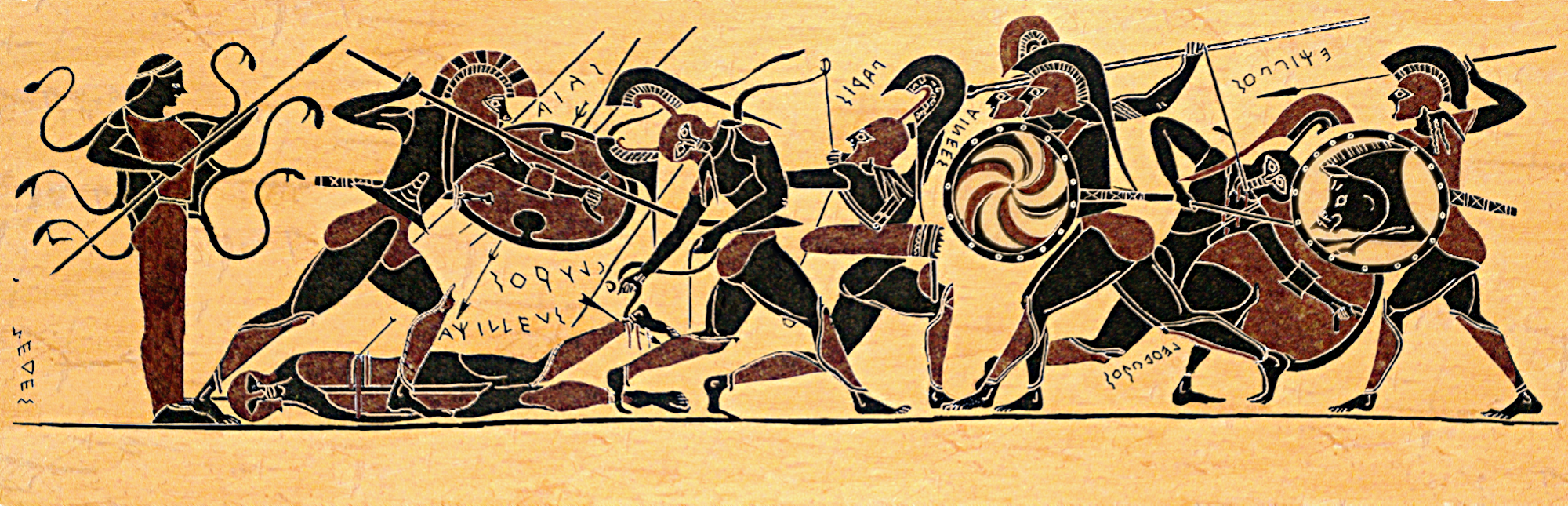

When Aeneas (with swirled shield) recalls this moment, will it be with pleasure? (From Andreas Rumpf?s ?Chalkidische Vasen,? from a lost Greek vase). (source)

When Aeneas (with swirled shield) recalls this moment, will it be with pleasure? (From Andreas Rumpf?s ?Chalkidische Vasen,? from a lost Greek vase). (source)

After losing to the Greeks, fleeing their burning city, and wandering around the Mediterranean en route to fulfill their leader?s destiny of founding Rome, the Trojans endure a horrifying ordeal at sea. They reach dry land where Aeneas tries to lift their spirits, giving a speech in which he utters some of the most famous words in Latin, ?forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit? (1.203). Even outside of Classics, the line has been widely referenced everywhere from articles about Pirates baseball to the Real Housewives of Beverly Hills.

Not only is this line famous, it is also confusing. In a 1997 New York Times interview, celebrated translator Robert Fagles singled out this line as one that ?bedeviled? him:

(Fagles) asked if it would be acceptable for him to read a passage that bedeviled him. He got up, knelt on the carpet in front of his file cabinet and pulled out some pages. The passage was one of the most famous in ?The Aeneid.? In Latin it reads, ?Forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit.?

Fagles renders this line, ?A joy it will be one day, perhaps, to remember even this.? Is it really pleasing to think about a traumatic event? A reason this line bedevils readers is because ?please? is only one of the possible translations of iuvo. ?Help? makes much more sense and renders this line much less perplexing.

Despite other options, ?please? has become a reflexive choice for readers of Aeneas? famous speech to his despondent men. I know I am not alone in advising students in deference to the scores of translators who have all made the same choice. Our instinct to ignore ?help? as a viable option and instead translate iuvo as ?please? is grounded in centuries of precedent. After all, editions of the Aeneid from ?the most influential Renaissance Aeneid? by Thomas Phaer up through the most widely acclaimed modern editions make this exact same choice:

Thomas Phaer (1550) ?To think on this may pleasure be another day.?

John Dryden (1667): ?An hour will come, with pleasure to relate your sorrows past, as benefits of Fate.?

John Conington (1866): ?This suffering will yield as yet a pleasant tale to tell.?

Theodore Williams (1910): ?It well may be some happier hour will find this memory fair.?

C.S. Lewis (ca. 1930): ?Some day it will be pastime to recall this woe.?

Rolfe Humphries (1953): ?Some day, perhaps, remembering even this will be a pleasure.?

Robert Fitzgerald (1983): ?Some day, perhaps, remembering this even will be a pleasure.?

Sarah Ruden (2008): ?Someday you may recall today with pleasure.?

David Ferry (2017): ?Perhaps there will come a time when you remember these troubles with a smile.?

In addition to translations, analysis of the line always focuses on the future pleasantness of the memories. Judith Hallett?s succinct summary reflects a long and pervasive tradition: ?With these words, Aeneas tries to cheer a dispirited band of comrades by the observation that their painful present struggles may well become ? over time and through memory ? sources of pleasure.?

In our vernacular, this phrase is often used to describe situations that are difficult, not traumatic. When an experience is simply difficult, the passage of time can indeed help us view it in a more positive light. Aeneas? words make perfect sense in these scenarios.

Some events, however, are never pleasant to recall. When high school students look at this line with fresh eyes, invariably, they translate iuvabit as ?it will help.? Year after year, I reply, ?Here iuvo means ?please,? not ?help.?? Occasionally for good measure I add, ?Sometimes you have to look beyond the first entry in the dictionary.? Do we really, though?

While it might be pleasant to look back on challenging circumstances, no amount of time makes it pleasant to recall traumatic events. The difference between hard times and actual trauma is an important one. According to the Center for Disease Control, traumatic events are marked by ?a sense or horror, helplessness, serious injury, or the threat of serious injury or death.? By the time Aeneas utters these words, he and the rest of the Trojans have already experienced events that evoked a sense of horror and extreme helplessness. The Trojans face the threat of serious injury and death both during the fall of Troy and a shipwreck so harrowing that it causes Aeneas to envy those who died in battle. Even after Aeneas attempts to raise the spirits of his men with his speech, we find out that he is merely pretending to be hopeful by masking his inner pain (1.209). It is doubtful Aeneas actually believes these memories will be pleasant one day.

There are alternatives to ?please? that make more sense in the context of the Trojans? adverse experiences and Aeneas? personal desperation. F.E.J. Valpy?s entry on iuvo in his Etymological Dictionary of Latin lists ?succor,? ?help,? and ?assist? as the primary meanings, followed by ?cure? and ?remedy.? In 1881, Georgius Thilo noted that many have preferred the meaning of usus erit (it will be useful) for iuvabit. In his 1553 translation of the Aeneid into Scots verse, Gavin Douglas uses ?help? for iuvabit: ?Sum tyme heiron to think may help perchance.? Much more recently in 2005, Stanley Lombardo translated this line, ?Someday, perhaps, it will help to remember those troubles as well.?

I contacted Dr. Lombardo to find out more about his choice for iuvabit. At the outset he said, ?Nobody has ever complained about it. In fact, nobody has ever noticed.? Choosing ?help? simply made more sense to him. ?I did not like ?please? somehow. For me, ?help? just struck the right chord. It is clear the act of remembering will have value.? This translation necessitated a different rendering of et. ?Et in that position can mean ?also,? and that is a different sort of notion than ?even,?? he explained. ?This et meaning shows how many terrible experiences they have had by now.?

?It will help? or ?it will be a remedy? make more sense as translations of iuvabit since remembering traumatic events is indeed helpful. Instead of telling his men they will find it pleasant to look back at these events, Aeneas is acknowledging that one day there will be relief in remembering. In the millennia since Aeneas conveyed this message, we have entire professions devoted to making sense of traumatic experiences and memories. Modern research on trauma supports the idea that it will be helpful to remember these things. Richard McNally, author of Remembering Trauma, writes, ?Recovering and integrating (traumatic memories) into meaningful narratives produces therapeutic benefits.?

This perspective runs counter to the advice of ancient thinkers whose proposed forgetting as a remedy for pain of past events. Cicero writes about this in his De Finibus:

Sed ut iis bonis erigimur, quae expectamus, sic laetamur iis, quae recordamur. stulti autem malorum memoria torquentur, sapientes bona praeterita grata recordatione renovata delectant. est autem situm in nobis ut et adversa quasi perpetua oblivione obruamus et secunda iucunde ac suaviter meminerimus. sed cum ea, quae praeterierunt, acri animo et attento intuemur, tum fit ut aegritudo sequatur, si illa mala sint, laetitia, si bona.

But as we are encouraged by the things we look forward to, so we feel joy in the things we remember. Fools are tormented by the memory of bad times; good times from the past bring joy to wise people when they relive pleasant memories. We have the capacity to bury adversity almost into perpetual oblivion and to recall favorable events with pleasure and fondness. But when we focus our keen mind and attention on prior events, then pain follows if they are bad, happiness if they are good. (1.17)

A century later, Seneca also suggests suppressing unpleasant memories. For him, resilience is the source of pleasure, not the memory of the suffering itself. He even suggests using Aeneas? words as a pep talk in the midst of suffering. After the traumatic event subsides, however, he agrees with Cicero that it is counterproductive to look back on painful events:

Deinde acerbum fuit ferre, tulisse iucundum est; naturale est mali sui fine gaudere. Circumcidenda ergo duo sunt, et futuri timor et veteris incommodi memoria; hoc ad me iam non pertinet, illud nondum. In ipsis positus difficultatibus dicat: Forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit.

It is pleasant to have endured that which was painful to live through. It is natural to have joy as something bad ends. Therefore two things must be cut out: fear of the future and the memory of past suffering, since the latter does not pertain to me any more and the former does not pertain to me yet. Placed in these difficult situations, let it be said: Forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit. (Epistulae Morales, 78.14)

Both Cicero and Seneca assume man can control his access to the past via memory. Traumatic memories are very different from other kinds of memories, however. After trauma, traumatic events are at the forefront of the mind, destined to replay interminably. This seems to be the case for Aeneas immediately after the shipwreck. He doesn?t remember the events, he relives them and fears ascribing words to his experience. When Dido asks Aeneas to tell his story, he replies, ?You order me to relive unspeakable pain, queen? (Infandum, regina, iubes renovare dolorem, 2.3). Right before he agrees to share his story, he says, ?Although my mind trembles to remember and seeks relief from the pain, I will begin? (quamquam animus meminisse horret luctuque refugit, incipiam, 12?13). During the story, he interrupts himself to describe the distress he is experiencing in real time: ?I bristle as I recount this? (horresco referens, 2.204).

In order to avoid reliving traumatic events, many people who have experienced trauma attempt to bury them, as Cicero advises. Though appealing, this strategy is not effective because, according to Keith Payne and Elizabeth Corrigan, ?Emotional memories (are) persistent, loitering even when asked to leave.? Suppressing memories is not just an ineffective way to diminish suffering. It can also make matters worse. Judith Herman in her seminal book Trauma and Recovery writes:

Traumatized people deprive themselves of those new opportunities for successful coping that might mitigate the effect of the traumatic experience. Thus, constrictive symptoms, though they may represent an attempt to defend against overwhelming emotional states, exact a high price for whatever protection they afford. They narrow and deplete the quality of life and ultimately perpetuate the effects of the traumatic event.

While these traumatic memories loiter, even the most diligent efforts to move forward are futile. Judith Herman explains, ?She finds herself caught between the extremes of amnesia or reliving the trauma, between floods of intense, overwhelming and the arid states of no feeling at all.? Furthermore, buried memories can lead to a sense of self-alienation. Bessel Van Der Kolk writes in The Body Keeps Score, ?As long as you keep secrets and suppress information, you are fundamentally at war with yourself.? Even when memories are painful, there are benefits to remembering and confronting them. Professor Ross Cheit of the Recovered Memory Project at Brown University told me, ?Remembering is literally enlightenment, possibly of the most personal kind. It?s also about the integrity of your own sense of identity.?

Aeneas? words make the most sense as a remedy for his fellow Trojans, instead of a suggestion that somehow the worst days of their lives will be a source of future pleasure. As the eponymous character in Rome?s national epic, Aeneas conveys power of memory and narrative. It might not be convenient for the memories to be at the forefront of the Trojans? minds immediately after their shipwreck, but deleting them is not a solution either. Instead, it will be helpful one day to integrate these experiences into their personal and collective experience and identity. In telling his men forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit, Aeneas provides an alternative to suppressing these memories and deleting part of their personal and collective history. Through these words, he gives his men hope for a future in which the events will be available as a memory they can recall at will instead of a nightmare they relive involuntarily.

Why has ?help? been overlooked for so long even if it makes more sense? Dr. Lombardo seemed surprised there were so few other translators who had made this same choice. ?Something catches on,? he said, ?and it becomes canon.? One day, perhaps, it will be helpful to have challenged even these things.

Dani Bostick teaches high school Latin and an occasional micro-section of ancient Greek in Virginia where she lives with her husband, children, and muppet-like dogs. She has published many collections of Latin mottoes online,has a strong presence as an activist for survivors of sexual violence on twitter, and is available to write, speak, or rabble-rouse.