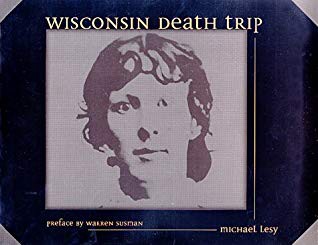

To begin with, there is the book?s wonderfully neo-Gothic title: Wisconsin Death Trip. One glance at that ripe offering and it?s hard to imagine anyone turning away without wanting to at least take a peek inside.

Authored by Michael Lesy and published in 1973, this non-fiction work, labeled by many today as a cult classic, looks at the darker side of the great American Dream, circa 1890 in rural Wisconsin. The result is at times laughably absurd and strangely unsettling.

Whatever personal attachment I have to this book may be indirect and circumstantial at best, but I?ll get to that later. First, a little background.

Lesy is a writer and professor of literary journalism at Hampshire College in Massachusetts. In a statement posted on Hampshire?s College?s website, Lesy describes his working theme as using ?historical photographs from public archives?to tell a variety of difficult truths about our country and our shared pasts.?

Wisconsin Death Trip would become his first, and most famous, published effort to date. And it all came about because one day the young scholar got tired of studying.

In 1972 Lesy was studying for his masters degree in American social history at the University of Wisconsin. One afternoon he decided he needed a break.

?I was really quite bored,? he would later say of the day when he started paging through a photography book and came across an old picture published by the Wisconsin Historical Society. On a whim he walked over to the very same Wisconsin Historical Society building on the Madison campus and asked if he could see some more.

What he found was a collection of portraits taken in the late 1800s by one Charles Van Schaick, the town photographer and Justice of the Peace in the town of Black River Falls, Wisconsin.

Lesy pored over thousands of Van Schaik?s old photographs that afternoon in Madison and saw something haunting start to emerge from the grim Scandinavian faces staring back at him.

His first impulse was to somehow tell the story of these pioneering people in the form of a documentary film. But he was quick to realize the more practical approach would be to compile these pictures in a book and let them tell the story instead.

Following up on his newfound inspiration, he started scouring through newspaper archives of The Badger State Banner from the 1890s, sifting and picking out any bizarre reports that complemented the dark vision he had seen reflected in Van Schaik?s subjects.

What he found was a treasure trove of stories referencing madness, suicide, disease and crime in the hinterlands of Wisconsin.

These snippets would become the other half of his picture book. By combining words and pictures in just the right way Lesy hoped to create a black and white montage of images no reader would soon forget.

Michael Lesy

Michael Lesy

A few samples:

? ?James Carr, residing in the town of Erin, Vernon County, was discovered dead in his log house recently, having died of starvation.?

? ?Mrs. Carter, residing at Trow?s Mill, who has been in charge of the boarding house at A. S. Trow?s cranberry marsh, was taken sick at the marsh last week and fell down, sustaining internal injuries which have dethroned her reason. She has been removed to her home here and a few nights since arose from her bed and ran through the woods?. A night or two after she was found trying to strangle herself with a towel?. It is hoped the trouble is only temporary and that she may soon recover her mind.?

? ?Lena Watson of Black River Falls gave birth to an illegitimate child and choked it to death.?

? ?Alexander Gardapie, aged 90 years, died at Prairie du Chien. He walked into a saloon, drank a glass of gin, asked the time of day, sat down, and died.?

? ?G. Drinkwine, father of Miss Lillian Drinkwine, attempted suicide a few days ago at Sparta. He swallowed a large quantity of cigar stubs.?

Or finally, this charming little sketch:

? ?Frederick Schultz, an old resident of Two Rivers, cheated his undertaker by suddenly jumping out of the coffin in which, supposed to be dead, he had been placed.?

To these and other macabre little stories it might be all a good Norwegian could do to shake his head slowly and say, ?Uff da.?

Were these incidents just isolated oddities, or were they more telling of what life was really like back then? Michael Lesy figured the answer to both questions was yes.

Reading through the accounts in Death Trip today, one is left to wonder ? only half in jest ? if the entire countryside wasn?t awash with crazies. Well, times were indeed tough back then, especially for the farmers and homesteaders who had little money to begin with.

All across the country in 1893, a run of bank failures and the depletion of the gold reserve set off an economic depression that quietly became ?one of the worst in American history,? and many folks in Wisconsin felt hardship like never before. Doubtless a fair number did fall prey to madness and suicide as a result.

And why not? Back then, facing an empty bank account or a child rasping for dear life with diptheria, or looking out over a season?s failed harvest and wondering how food was going to be put on the table, who wouldn?t question their ability to make it through another day?

In an interview in 2003, Lesy said that the aim of any book should be to ?allow the reader the ability to free associate and not be lost.?

That?s what the reader is invited to do with Wisconsin Death Trip once the pages start turning. The mind starts to skim across the photographs and in free association ponder what was going on in the life of each of these people when their picture was taken? What hardships could have pushed some to taking such grisly extremes written about in the local papers?

Photo by Jakob Owens on Unsplash

Photo by Jakob Owens on Unsplash

In other words, maybe the good old days of yesteryear weren?t so good after all.

As books go, Death Trip defies convention in nearly every way. For one thing, none of the pictures carry any captions or descriptions. The faces one sees throughout the book are nameless ghosts. The text has no clear beginning or narrative structure. The pages aren?t even numbered.

It?s a cover-to-cover read like no other you will find.

Much of my interest in all this stems from the fact that part of my family tree runs right through Black River Falls in the same time period detailed in the book. At the turn of the century my grandmother, Margaret Stamstad, was a girl growing up in the rural township of Irving, ten miles southeast of Black River Falls and Charles Van Schaik?s photography studio. Fortunately for my mother ? and by extension me ? she went on to marry and raise her family, though in her time she endured burdens and hardships that, with lesser women, might have easily derailed all that.

While only in her teens she had to endure the death of one of her sisters from an unknown digestive ailment. Then some years later, tragedy struck again when her own son was born with a congenital birth defect with his esophagus that basically prevented him from keeping food down. It wasn?t long before he succumbed to starvation and died when he was only four months old.

That any mother could find the resolve to go on after such terrible darkness seems nothing short of a miracle, but maybe miracles of that sort were somehow more commonplace back then.

My grandmother had to run the family farm without her husband after he suffered a series of debilitating strokes and died in 1946. Then on top of all that was a diagnosis of breast cancer and a slow and painful recovery from a radical mastectomy.

So?tough times? Most of us today have no idea.

The book takes a strangely entertaining look at the journey which brought our descendants and ultimately each one of us to where we are today. What?s more, it invites us to reflect on what we consider the trials and tribulations of our own lives and measure them against all that came before.

It?s a powerful history lesson, one worth revisiting from time to time, as the author reminds us when he writes in the conclusion to the book:

?Pause now. Draw back from it. There will be time again to experience and remember.?

And remember we should.