The power of a negative space is in its capacity to disrupt your normal expectations of reality

Black Square (1915), by Kazimir Malevich. Source Wikimedia Commons

Black Square (1915), by Kazimir Malevich. Source Wikimedia Commons

The space left behind when a picture is removed from a wall creates an impression of absence. Sunlight has perhaps bleached the wall by subtle degrees, a change that is unnoticed until the picture frame is taken down and a lingering silhouette echoes the vanished item.

This negative space has something fundamental about it, something dug-up, eternal even. The power of a negative space is in its capacity to disrupt our normal expectations of reality. Like the impression left floating across your eyes when you stare at something for too long, a negative space is like peering at something that is no longer there.

The power of a negative space is in its capacity to disrupt your normal expectations of reality.

The ghosts of negative spaces

A similar absence is unearthed when a piece of furniture that has occupied the same spot for years is eventually moved. A sofa that has lived in the same place for a decade will build up a whole trove of detritus beneath it: old magazines, kitchen catalogues, fashion brochures, a pair of slippers, a coffee coaster, a lost TV remote, old birthday cards you didn?t know what to do with, all arranged into an intricate rectangle for which no pre-plan had been conceived, framed with a halo of dust that the vacuum cleaner could not reach.

Dismantle a whole room and the event is spectral. It is hard not to use the word ghostly to describe it, as the family of absences that presents itself appears to revise the very ambience of the space. With the furniture gone, a series of personal memories begins to overlay one another ? nostalgia glimmering with a hundred facets ? as the past life of the room is somehow amassed and dissolved in the same instant.

When an entire house or street is demolished, it is perhaps more difficult to imagine what was there before, simply because so much has been altered. Many generations may have lived and worked in this place, a deep presence that is annulled with the first thump of a wrecking ball.

When, in 1990, a house in London was earmarked for demolition, the artist Rachel Whiteread conceived to make a plaster cast of the entire living room. She described her aims as ?mummifying the air in a room?. The work, titled Ghost, is an inverted interior, a room-sized object memorializing a space that no one had ever (quite) seen before.

Ghost (1990) by Rachel Whiteread. Plaster on steel frame. Source Wikipedia

Ghost (1990) by Rachel Whiteread. Plaster on steel frame. Source Wikipedia

Whiteread?s art ? she has since created many casts of similar negative spaces ? solidifies the air into a tangible form, reminding us that our palpable reality is always a double-faceted entity. Just look around the room you are in and notice how the space is a faceted be so many edges. Air has corners, depth is extension: we make sense of our space by understanding its boundaries.

Negative spaces help you see the world unconventionally.

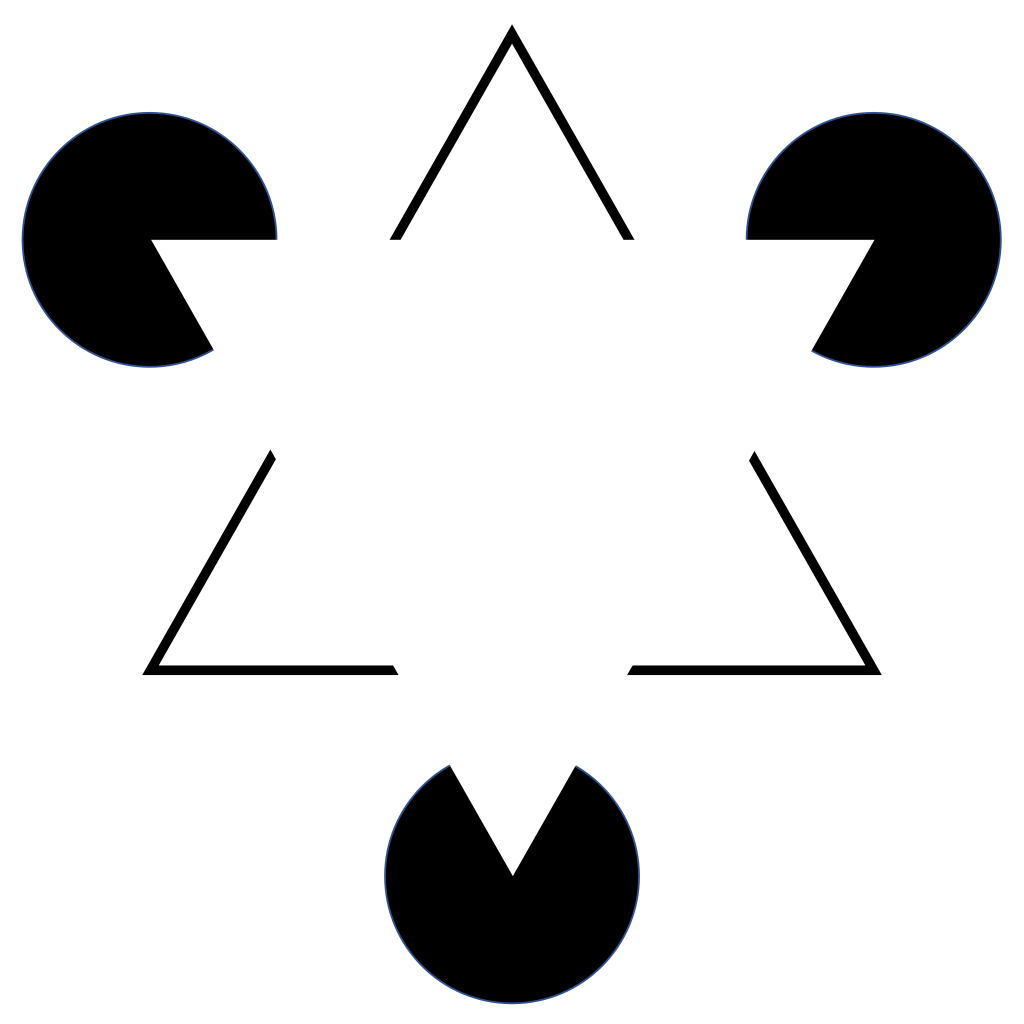

Like the optical illusions of so-called ?ambiguous images?, we begin to see that reality is created as much by habits of perception as by any underlying physical or literal truth.

A Kanizsa Triangle demonstrating the ambiguous nature of our perceptions. Source Wikimedia Commons

A Kanizsa Triangle demonstrating the ambiguous nature of our perceptions. Source Wikimedia Commons

Photographic film

The concept of turning negative forms into something positive, something perceptible, has its most familiar expression in photographic film. Photographs ? as they used to be made, with light-sensitive plastic ? stand out as exemplary bearers of reversed reality.

The camera film is coated on one side with tiny light-sensitive crystals which darken when exposed to light. The ?negative? film can then be used to create images in a second inversion onto paper, restoring light, shade and color to their everyday appearance.

I remember as a child holding up strips of brownish acetate and peering into the tiny frames, trying to calculate how exactly this silhouette of russet-green and umber-red could mutate into portraits of my family in the sanguine colors of real-life I was used to.

There is something remarkable and also strange about the migration of the negative film into a positive photo, as if the reality stored in a film transparency is only an apparition until it is printed on paper. Life literally inverted, captured in an other-worldly form until it is re-released. It brings to mind the 19th century French novelist, Balzac, who feared being photographed under the belief that with every photographic impression, a layer of his being had been taken from him and stored inside the image.

We still think of photographs as a way of storing moments of our lives: a holiday, a party, a romance. Photographs tend to be more stable than memories, though perhaps no more accurate. At any rate, we tend to take photographs in order not to forget how that particular moment was. As Susan Sontag described, ?To take a photograph is to participate in another person?s (or thing?s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability? All photographs testify to time?s relentless melt.? More recently on social media, under the euphemism ?sharing?, a photograph has become the means of testifying to the same melt of time, not for our own memories but for everyone else?s.

Negative spaces of prehistory and modern times

The transfer of a film negative to a photograph works essentially as a stencil, where the transparency of the film permits or prevents light from reaching the photographic paper. The concept of stencilling is known to be at least 40,000 years old, evidenced by prehistoric hand paintings discovered on cave walls across the world, from Argentina to France to Indonesia.

These images were typically made by placing the palm of the hand to a wall and then blowing or spitting painting onto it in order to leave behind a negative impression. They can perhaps be thought of as early versions of shadow hand puppetry, especially when you consider that the only available light source inside the cave would have been the dancing flame of a fire.

Hands at the Cuevas de las Manos upon Ro Pinturas, near the town of Perito Moreno in Santa Cruz Province, Argentina. Source Wikimedia Commons

Hands at the Cuevas de las Manos upon Ro Pinturas, near the town of Perito Moreno in Santa Cruz Province, Argentina. Source Wikimedia Commons

Light and shadow are intrinsic to the art of negative spaces. Not unlike the handprints of cave art, a ?photogram? is made by placing objects directly onto the surface of photographic paper and then exposing the paper to light so that only silhouettes are captured. The technique was used by artists such as Christian Schad and May Ray, and was associated with the Dada group of surrealists of the early 20th century. Described by Man Ray as ?cameraless photographs?, photograms rendered reality in the most dreamlike of ways.

Untitled Rayograph (1922), by Man Ray. Gelatin silver photogram. Source Public Domain

Untitled Rayograph (1922), by Man Ray. Gelatin silver photogram. Source Public Domain

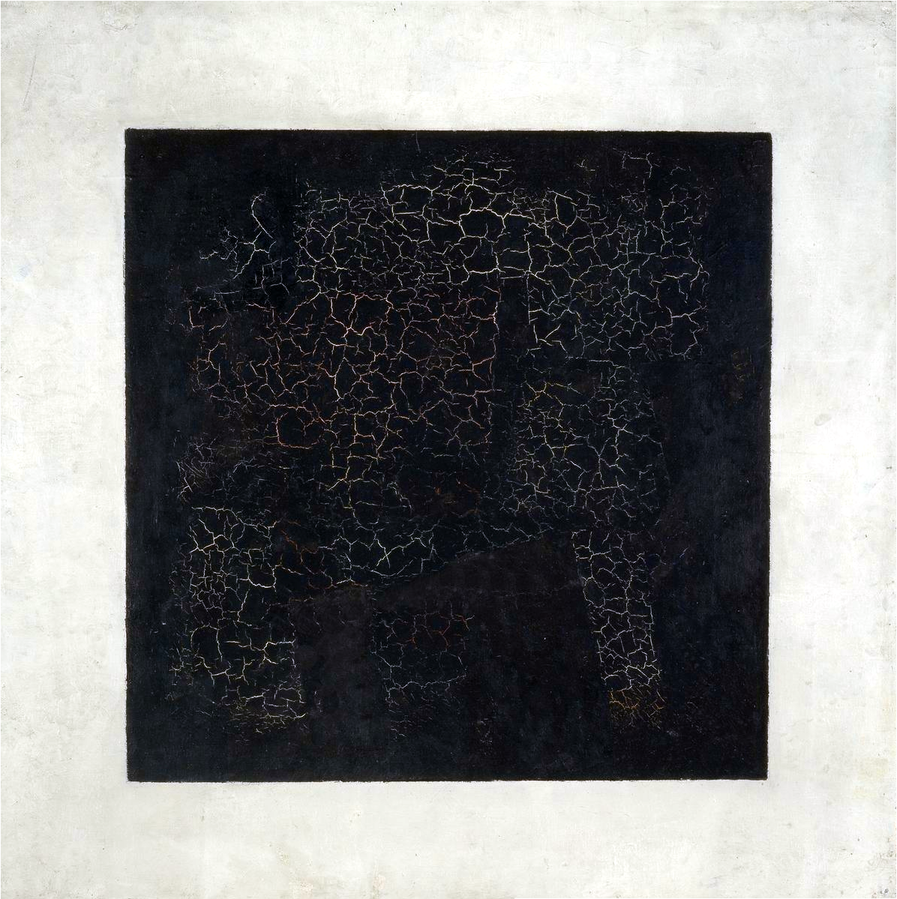

Art has remained fascinated by the ghost of the silhouette. Perhaps the ultimate image of negative space in art, or indeed anywhere else, is the 1915 painting Black Square by Kazimir Malevich.

Simply a black square with a white border, Malevich presented his painting as the ?face of the new art ? the first step of pure creation.? It is radically non-representational, a provocative dead-end work of art that, according to Malevich, aspires to a form of mystical faith. It is a painting that is stubborn in its refusal to affirm anything that might be seen or touched. As such, it is negative space at its most confrontational and emphatic: an empty void, or else, like outer space itself, a dwelling place of a multitude of worlds we cannot see.

Black Square (1915), by Kazimir Malevich. Source Wikimedia Commons

Black Square (1915), by Kazimir Malevich. Source Wikimedia Commons

With its white border, Black Square is also reminiscent of the blank space left behind when a picture removed from a wall. So we come full circle.

This, however, would have to be a picture that has hung in the same place for eons, not just years, one that has left behind a sooty, black-dust silence into which we can project any number of our own ideas and memories, large or small, singular or infinite.

Christopher P Jones writes about art and culture at his website. Sign up for more.