Listen to this story

–:–

–:–

New state law requires manufacturers to list menstrual product ingredients, but it?s unclear exactly what will be included

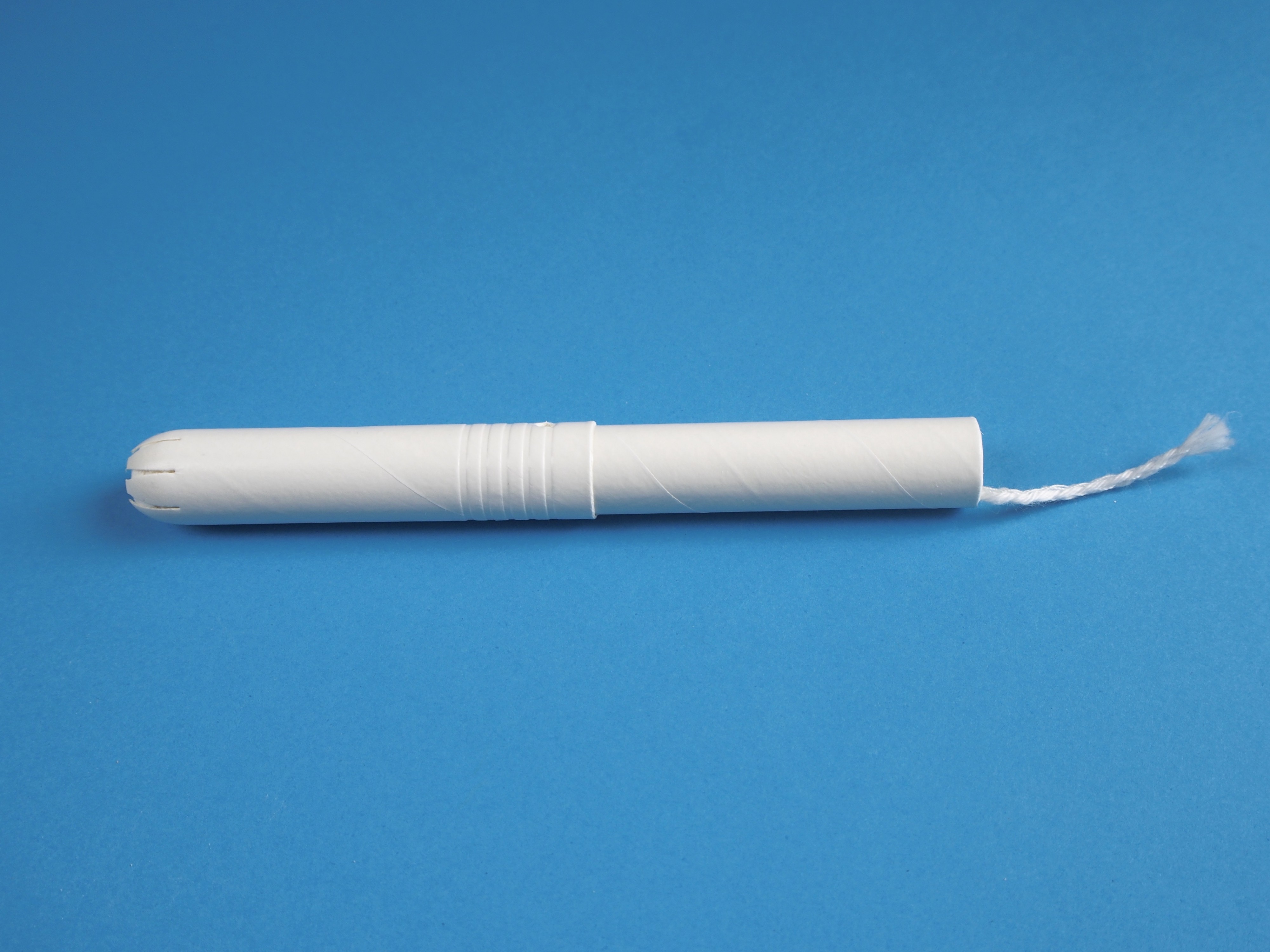

Photo: alexat25/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Photo: alexat25/iStock/Getty Images Plus

In October, New York passed the first law in the United States mandating that tampons and other menstrual products include a detailed ingredient list so consumers can be better educated about what they?re putting in their bodies.

In October, New York passed the first law in the United States mandating that tampons and other menstrual products include a detailed ingredient list so consumers can be better educated about what they?re putting in their bodies.

?We have ingredient disclosure for everything, but not for this,? says Linda Rosenthal, the New York assembly member who sponsored the bill. ?[It?s] ridiculous that we use these products, put them inside our bodies, and we don?t even know what?s in them.?

The main ingredient in a tampon is either cotton, viscose rayon (a fiber made from processed wood pulp), or a combination of the two. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which regulates tampons like a medical device, considers both materials safe. But some researchers say those ingredients don?t tell the whole story, and that tampons could be exposing women to dangerous toxins present in the absorbent fibers. How big of a risk those chemicals actually pose ? and whether they?ll be covered in the new law ? is still up for debate, and there?s scant research studying the connection between toxin exposure in tampons and health problems down the line.

The most commonly cited concern is dioxin, a chemical that has been linked to cancer and endometriosis in women. Dioxin is a byproduct of the bleaching process manufacturers use when they purify rayon using chlorine. Because of this risk, the FDA now recommends that companies use only chlorine-free bleach and says dioxin levels in tampons are negligible.

The other concern regarding chemical exposure through tampons is that both cotton and rayon come from highly absorbent plants, meaning they can soak up pesticides and heavy metals present in the soil where they?re grown.

One of the only research studies to test tampons for dioxin levels, published in 2002, backs up this claim, stating that ?exposures to dioxins from tampons are approximately 13,000?240,000 times less than dietary exposures.? (Approximately 95% of people?s exposure to dioxin comes from eating animal products.) The authors of the study conclude that although dioxins are found in trace amounts in both cotton and rayon tampons, they do not ?significantly contribute to dioxin exposures in the United States.?

?Your hamburger from McDonald?s probably poses a greater health risk from dioxins in foodstuff than the dioxins present in the tampon you may have been using when you went to McDonald?s,? says Lewis Wall, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Washington University in St. Louis, who was not involved in the research.

The other concern regarding chemical exposure through tampons is that both cotton and rayon come from highly absorbent plants, meaning they can soak up pesticides and heavy metals present in the soil where they?re grown. ?Cotton is one of the most heavily pesticized [sic] crops in the United States,? says Marianthi-Anna Kioumourtzoglou, an assistant professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University. ?Cotton is also very good at taking up heavy metals from the ground, so if the cotton fields are near industrial fields, for example, and those heavy metals are deposited in the soil or are found in the water that?s used to water cotton, then that might also be an issue.?

Concerned about potential heavy-metal exposure, Kioumourtzoglou tested 255 women to see whether those who used tampons had higher levels of cadmium, lead, and mercury in their blood than women who used another type of menstrual product. Her study did not find a significant difference in metal levels between the two groups, although she still believes concern is warranted.

The FDA recommends companies test their tampons for both dioxin and pesticides, but the manufacturers do not have to disclose whether the chemicals are present. Some women?s health advocates say that?s not good enough, and that the FDA is minimizing a real health risk.

If a woman uses a tampon 24 hours a day for five days every month for 30 years, she will have a tampon in her vagina for a combined five years of her life.

?If you?re using a single tampon, the FDA says, ?Well, it?s minuscule, the amount of dioxin in a tampon,?? says Philip Tierno, a clinical professor in the Department of Pathology at New York University Langone School of Medicine. ?That?s true, it is minuscule. But it?s nice to know what that level is, mainly because you don?t use one tampon. In a lifetime, a woman may use 12,000 tampons.?

If a woman uses a tampon 24 hours a day for five days every month for 30 years, she will have a tampon in her vagina for a combined five years of her life. Because of the large network of capillaries found there, the vagina is extremely absorbent, so any chemicals present will be taken up directly into the bloodstream. Some argue that there could be a buildup of exposure over time, though there?s no data to say so definitively.

It?s unclear whether the New York law, which goes into effect in April 2020, will force companies to list pesticides used in growing the fibers or any chemical byproducts produced during the manufacturing process. Assembly Member Rosenthal agrees that the law will be most useful if it requires companies to list these types of trace ingredients, but when Elemental spoke with her, she could not answer whether or not the law will require that level of specificity. How the bill is currently worded suggests that these types of chemicals will not be listed: ??Ingredient? shall mean an intentionally added [emphasis added] substance present in the menstrual product.? This language is a marked change from the bill?s original wording: ??Ingredient? shall mean a substance present in any quantity in the menstrual product.?

Tierno and Kioumourtzoglou say women who prefer no level of exposure should consider using a pad or a menstrual cup made from silicon instead of a tampon.

However, Wall, the gynecologist, says safety concerns around tampon ingredients are overblown. ?In the great scheme of women?s health issues, the safety of pads and tampons is a lower priority than a number of other things.?