Do you click that green run button, but don?t really know what?s going on under the hood? Do you want to know how a programming language works? Let?s crack the case wide open with compilers in this article.

This post discusses the major concepts in compilers like tokenization, grammars, parsing, and code generation. Not enough? I include lots of learning resources ? so any time you hear something interesting, look for the closest link containing the information you?re looking for.

There?s a New Version!

Understanding Compilers ? For Humans (Version 2)

How Programming Languages Work

towardsdatascience.com

Note to reader

When I started writing this article, I targeted anyone, regardless of prior knowledge. I got carried away and just started throwing in technical details too. Now, I suggest this be read by someone with programming experience. Otherwise the significance may not be there.

Introduction

All a compiler is, is just a program. The program takes an input (which is the source code ? aka a file of bytes or data) and generally produces a completely different looking program, which is now executable; unlike the input.

On most modern operating systems, files are organized into one-dimensional arrays of bytes. The format of a file is defined by its content since a file is solely a container for data, although, on some platforms the format is usually indicated by its filename extension, specifying the rules for how the bytes must be organized and interpreted meaningfully. For example, the bytes of a plain text file (.txt in Windows) are associated with either ASCII or UTF-8 characters, while the bytes of image, video, and audio files are interpreted otherwise. (Wikipedia)(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Computer_file#File_contents)

The compiler is taking your human-readable source code, analyzing it, then producing a computer-readable code called machine code (binary). Some compilers will (instead of going straight to machine code) go to assembly, or a different human-readable language.

Human-readable languages are AKA high-level languages. A compiler that goes from one high-level language to a different high-level language is called a source-to-source compiler, transcompiler or transpiler.(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Source-to-source_compiler)

int main() { int a = 5; a = a * 5; return 0;}

The above is a C program written by a human that does the following in a simpler, even more human readable language called pseudo-code:

program ‘main’ returns an integerbegin store the number ‘5’ in the variable ‘a’ ‘a’ equals ‘a’ times ‘5’ return ‘0’end

Pseudocode is an informal high-level description of the operating principle of a computer program or other algorithm. (Wikipedia)(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pseudocode)

We will compile that C program into Intel-style assembly code just like a compiler does. Although a computer has to be specific and follow algorithms to determine what makes words, integers, and symbols; we can just use common sense. That in turn, makes our disambiguation much shorter than for a compiler.

This analysis is simplified for easier understanding.

Tokenization

Before a computer can decipher a program, it must first split every symbol up into its own token. A token is the idea of a character, or grouping of characters, inside of a source file. This process is called tokenization, and it is done by a tokenizer.

Our original source code would be split up into tokens and kept inside of a computer?s memory. I will try to convey the computer?s memory in the following diagram of the tokenizer?s production.

Before:

int main() { int a = 5; a = a * 5; return 0;}

After:

[KEYWORD,”int”] [ID,”main”] [LPAREN] [RPAREN] [LBRACE] [KEYWORD,”int”] [ID,”a”] [EQUALS] [INT,”5″] [SEMICOLON] [ID,”a”] [EQUALS] [ID,”a”] [MULTIPLY] [INT,”5″] [SEMICOLON] [KEYWORD,”return”] [INT,”0″] [SEMICOLON][RBRACE]

Diagram is hand formatted for readability. In actuality, it would not be indented or split by line.

As you can see, it creates a very literal form of what was given to it. You should be able to nearly replicate the original source code given only the tokens. Tokens should retain a type, and if the type can be of more than one value, the token should also contain the corresponding value.

The tokens themselves are not enough to compile. We need to know the context, and what those tokens mean when put together. That brings us to parsing, where we can make sense of those tokens.

Parsing

The parsing phase takes tokens and produces an abstract syntax tree, or AST. It essentially describes the structure of the program, and can be used for determining how it is executed, in a very ? as the name suggests ? abstract way. It is very similar to when you made grammar trees in middle school English.

The parser generally ends up being the most complex part of the compiler. Parsers are complex and require lots of hard work and understanding. That is why there are lots of programs out there that can generate an entire parser depending on how you describe it.

These ?parser creator tools? are called parser generators. Parser generators are specific to languages, as they generate the parser in that language?s code. Bison (C/C++) is one of the most well known parser generators in the world.

The parser, in short, attempts to match tokens to already defined patterns of tokens. For example, we could say assignment takes the following form of tokens, using EBNF:

EBNF (or a dialect, thereof) is commonly used in parser generators to define the grammar.

assignment = identifier, equals, int | identifier ;

Meaning the following patterns of tokens are considered to be an assignment:

a = 5ora = aorb = 123456789

But the following patterns are not, even though they should be:

int a = 5ora = a * 5

Those that do not work are not impossible, but rather require further development and complexity inside of the parser before they can be implemented entirely.

Read the following Wikipedia article if you are interested more in how parsers work. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parsing

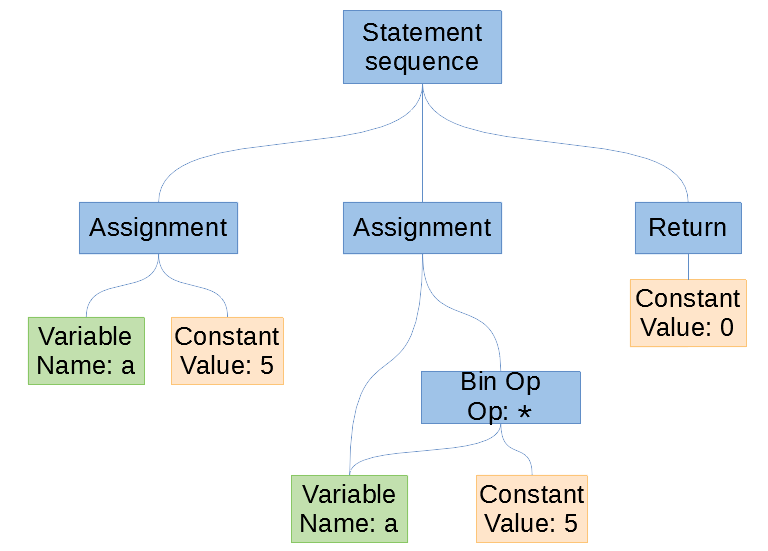

Theoretically, after our parser is done parsing, it would generate an abstract syntax tree like the following:

The abstract syntax tree of our program. Created using Libreoffice Draw.

The abstract syntax tree of our program. Created using Libreoffice Draw.

In computer science, an abstract syntax tree (AST), or just syntax tree, is a tree representation of the abstract syntactic structure of source code written in a programming language. (Wikipedia)(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abstract_syntax_tree)

After the abstract syntax tree lays out the high-level order of execution, and the operations to perform, it becomes pretty straight-forward to begin generating assembly code.

Code Generation

Since the AST contains branches that almost entirely define the program, we can step through those branches, sequentially generating the equivalent assembly. This is called ?walking the tree?, and it is an algorithm for code generation using an AST.

Code generation immediately after parsing is not common for more complex compilers, as they go through more phases before having a final AST, such as intermediate, optimization, etc. There are more techniques for code generation.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_generation_(compiler)

We compile to assembly because a single assembler can produce machine code for either one, or a few different CPU architectures. For example, if our compiler generated NASM assembly, our programs would be compatible with Intel x86 architectures (16-bit, 32-bit, and 64-bit). Compiling straight to machine code would not be as effective, because we would need to write a backend for each target architecture independently. Although, it would be pretty time consuming, and with less gain than using a third-party assembler.

With LLVM, you can just compile to LLVM IR and it handles the rest. It compiles down to a wide range of assembler languages, and thus compiles to many more architectures. If you?ve heard of LLVM before, you probably see why it?s so cherished, now.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LLVM

If we were to step into the statement sequence?s branches, we would find all of the statements that are run from left to right. We can step down those branches from left to right, placing the equivalent assembly code. Every time we finish a branch, we have to go back up and begin working on a new branch.

The leftmost branch of our statement sequence contains the first assignment to a new integer variable, a. The assigned value is a leaf that contains the constant integral value, 5. Similar to the leftmost branch, the middle branch is an assignment. It assigns the binary operation (bin op) of multiplication between a and 5, to a . For simplicity we just reference a twice from the same node, rather than having two a nodes.

The final branch is just a return and it is for the program?s exit code. We tell the computer it exited normally by returning zero.

The following is the production of the GNU C Compiler (x86?64 GCC 8.1) given our source code using no optimizations.

Keep in mind, the compiler did not generate the comments or spacings.

main: push rbp mov rbp, rsp mov DWORD PTR [rbp-4], 5 ; leftmost branch mov edx, DWORD PTR [rbp-4] ; middle branch mov eax, edx sal eax, 2 add eax, edx mov DWORD PTR [rbp-4], eax mov eax, 0 ; rightmost branch pop rbp ret

An awesome tool; the Compiler Explorer by Matt Godbolt, allows you to write code and see compiler?s assembly productions in real-time. Try our experiment at https://godbolt.org/g/Uo2Z5E.

The code generator usually attempts to optimize the code in some way. We technically never use our variable a. Even though we assign to it, we never read it again. A compiler should recognize this and ultimately remove the entire variable in the final assembly production. Our variable stayed in because we did not compile with optimizations.

You can add arguments to the compiler on the Compiler Explorer. -O3 is a flag for GCC that means maximum optimization. Try adding it, and see what happens to the generated code.

After the assembly code has been generated, we can compile the assembly down to machine code, using an assembler. The machine code only works for the single target CPU architecture. To target a new architecture, we need to add that assembly target architecture to be producible by our code generator.

The assembler you use to compile the assembly down to machine code is also written in a programming language. It could even be written in its own assembly language. Writing a compiler in the language it compiles is called bootstrapping.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bootstrapping_(compilers)

Conclusion

Compilers take text, parse and process it, then turn it into binary for your computer to read. This keeps you from having to manually write binary for your computer, and furthermore, allows you to write complex programs easier.

Backmatter

Thank You

And that is it! We tokenized, parsed, and generated our source code. I hope you have a greater understanding of computers and software after having read this. If you are still confused, just check out some of the learning resources I have listed at the bottom. I never had all of this down after reading one article. If you have any questions, look to see if anyone else has already asked it before taking to the comment section.

Resources

I only touched the surface. If you are still interested, continue learning with these resources.

- http://craftinginterpreters.com/

- https://youtu.be/QXjU9qTsYCc

- https://medium.com/@CanHasCommunism/making-a-brainf-ck-to-c-compiler-in-rust-10f0c01a282d

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shunting-yard_algorithm