Bill Bernbach had a problem. Carl Hahn had contracted his agency, Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB) to promote a car called the Volkswagen in the United States. Bernbach?s problem was that Hahn?s call came at the end of the fifties, when America was in a deep love affair with stylish vehicles made in Detroit, USA. How could DDB sell an small, ugly, cheap, foreign car that Hitler had a hand in creating ? to the American public? Luckily for Hahn, Bill Bernbach was the most innovative ad man of his time, being a key player in what is today known as the Creative Revolution. The campaign that DDB put together for Volkswagen in 1959 would not only make their car ?as American as apple pie? but be recognised by Advertising Age as being the greatest ad of all time and change the industry forever.

Early advertisement for Snake Oil.

Early advertisement for Snake Oil.

The advertising industry is a recent one. Up until the early twentieth century, the primary job of an advertiser was to buy and sell space in a newspaper on behalf of a client. Eventually these clients started asking the advertisers to not just buy space but write the advert too. Unfortunately, many of the earlier products advertisers looked after were of the snake oil variety (since these ?miracle products? were usually nothing more than coloured water, the companies selling them could afford large ad budgets). This didn?t help the public?s view of the fledgling advertising business, an impression that hasn?t changed a great deal.

Post Second World War, the role of the advertiser changed significantly. A booming economy meant a dramatic increase in the number of products on shop shelves. There was not just one brand of aspirin anymore, there were ten. Self service had arrived in the form of the supermarket, meaning that shopkeepers could no longer offer their personal recommendations. New technologies led to new inventions which needed explaining to a bewildered public. Advertisers were in the position of needing to differentiate the products of their clients; and as manufacturers made more money so did their advertising expenditure increase.

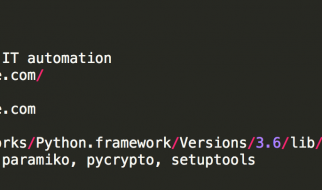

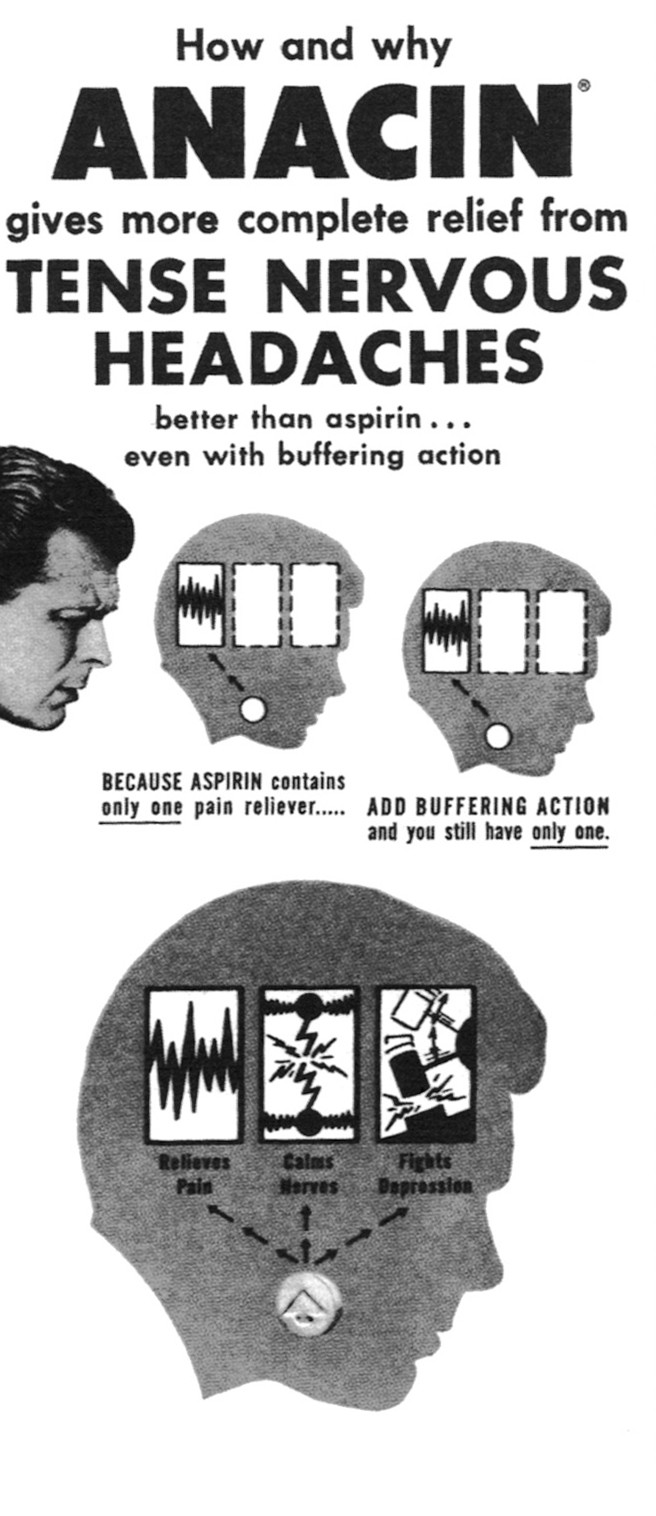

Anacin aspirin ad.

Anacin aspirin ad.

Several ideas formed the basis of pre-1960s advertising. A popular idea still used today has its origins in the 1940s. It is the Unique Selling Proposition (USP), a term coined by Rosser Reeves. The simple idea behind a USP is to highlight a benefit of a product which competitors did not have. This benefit would then be hammered home again and again. One of the most famous campaigns created by Reeves was for Anacin aspirin. The noisy and repetitive TV commercials (?fast, fast, incredible fast pain relief?) are not fondly remembered.

Another of Reeves? beliefs was that research should form the underpinnings of any campaign. Layouts, copy and other elements of an ad were all to be extensively tested and based in ?theory?. This helped relax clients who liked using the textbook and didn?t want to take risks on new and novel approaches. Reeves? philosophy on advertising was uncomplicated. He believed the only purpose of an ad campaign was to see the sales line moving in an upwards direction, regardless of how that was accomplished. Reeves warned against creativity in advertising, calling it ?the most dangerous word in all of advertising?.

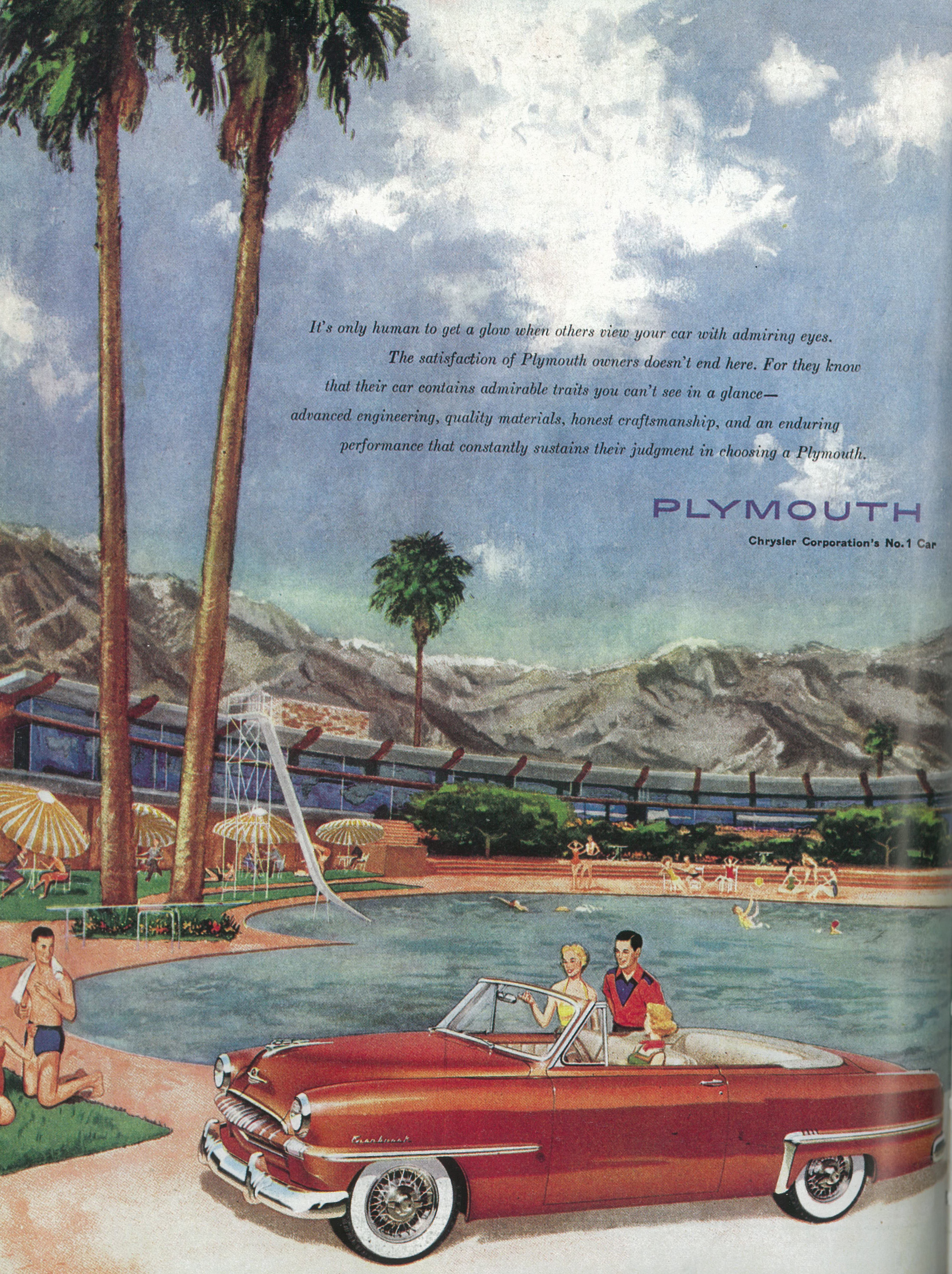

Plymouth, 1953.

Plymouth, 1953.

The field of psychology ? invented by Sigmund Freud ? was also influencing advertising. Psychologists were laying ? what they thought was ? the subconscious of the general public on display and ad men had no trouble in exploiting this. Much of the advertising from the fifties ? especially in vehicle advertising ? used status to continually drive sales and demand. To have the latest was to be modern, be up to date. Advertising depicted a world full of stylish individuals enjoying perpetual happiness.

As a result of the repetition coming from Madison Avenue, the general public was beginning to switch off. The status anxiety the ads created was beginning to frustrate. ?The Wall? was being erected between them and the ads they saw . Breaking through that wall was becoming harder to do. Advertising needed a new approach, and Bill Bernbach knew what that needed to be.

The Original Mad Man

In earlier days of advertising, the creative department had little control over the end result. The account people would tell the copywriters what to write, the copywriters would hand their work to the art department so their words could be placed into a layout. Often the copywriters never met the person who ended up doing the art and the layout. The reliance on research meant that the creatives were little more than technicians.

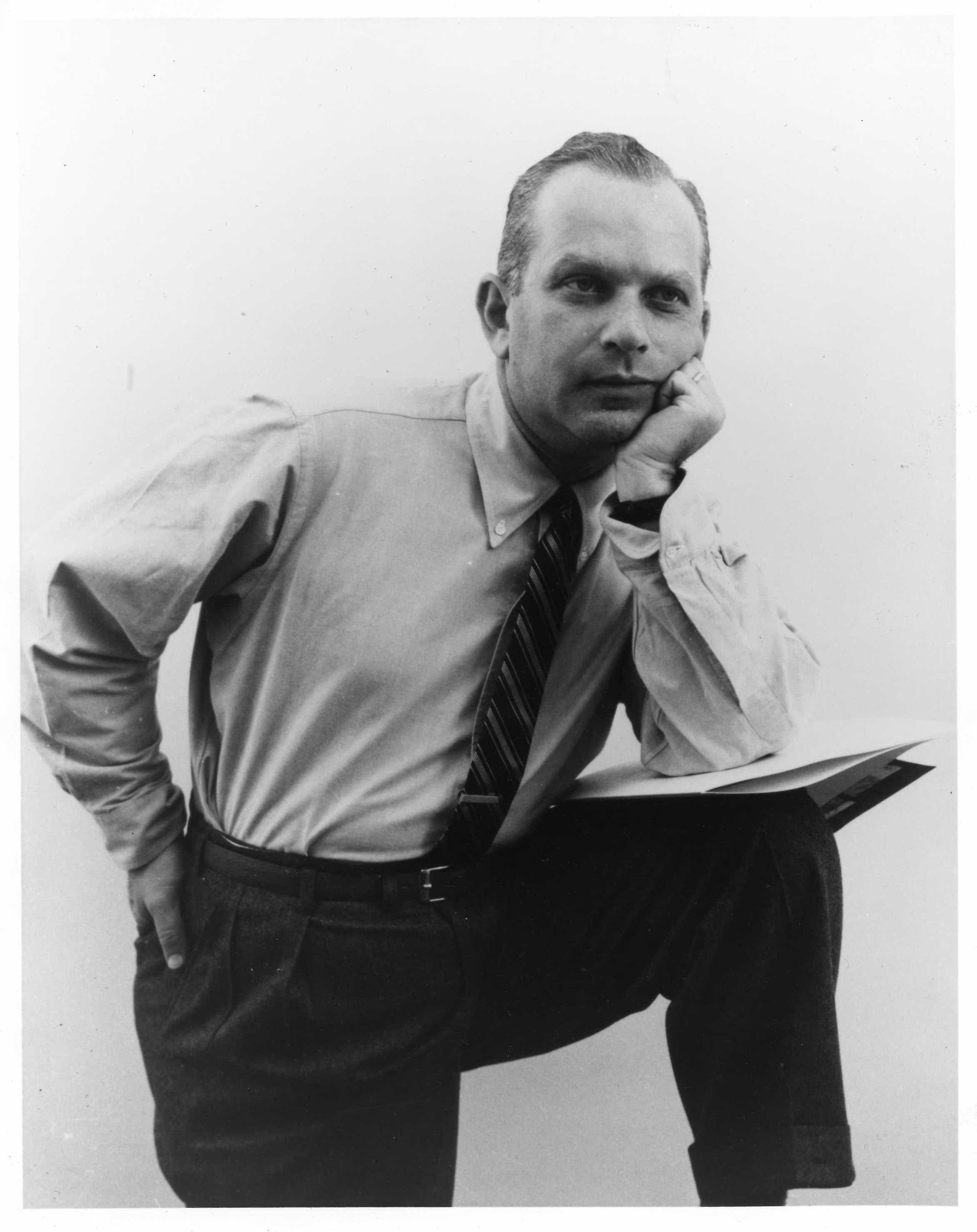

Bill Bernbach.

Bill Bernbach.

Bernbach?s philosophy seems obvious today but was revolutionary at the time. He believed in concept based advertising, in which an idea became the crucial ingredient of an ad. About 1940 he met Modernist Paul Rand, an influential graphic designer known for his blending of design and art. Rand was known for his edgy approach to images and their symbology. He used typography and illustration to create highly original pieces. The pair ended up working with each other at the Weintraub Advertising Agency. Both men believed that a singular idea should be the goal of a campaign and the two of them spent many lunch hours wandering the streets of Manhattan discussing their ideas.

Unfortunately the relationship ended when Bernbach was drafted into the army after Pearl Harbour. Luckily for him, a high blood pressure meant he only lasted a couple of months. Back in the civilian world, Bernbach continued to get frustrated at the state advertising was in. Working as a creative director at Grey Advertising in 1947, Bernbach wrote a letter which has since become famous. The letter was addressed to the Grey Board of Directors and was a plea to support creativity in advertising. He wrote: ?The danger lies in the temptation to buy routinised men who have a formula for advertising. The danger lies in the natural tendency to go after tried-and-true talent that will not make us stand out in competition but rather make us look like all the others.? He concluded with ?Let us blaze new trails. Let us prove to the world that good taste, good art and good writing can be good selling?.

This letter fell on deaf ears. Within a few years Bernbach left Grey and started his own agency with a couple of partners calling it Doyle Dane Bernbach. Free to set up his agency the way he wanted, DDB became known for its creative risk taking. Bernbach is quoted as saying: ?I have no rules for people. I just want them to do what comes natural to them, but to do it in an effective way. So that they?re doing their own thing, but they?re doing it in a sharp and disciplined way to make it work?.

The Strength Through Joy Car

Ferdinand Porsche.

Ferdinand Porsche.

The Volkswagen Beetle had a troubled start to its life. The Austrian Ferdinand Porsche was born in 1875 and had two dreams. The first was to build racing cars. Motorcars in early twentieth century Europe were generally viewed with suspicion, a plaything of the wealthy. Early vehicles were noisy and scared horses. It was the advent of motor racing that helped fuel the first wide spread enthusiasm for cars. Events were held throughout the continent and attracted widespread attention from the towns. It was only natural that the talented young Porsche would find the allure of building a racing car tempting. Unfortunately, his earlier employers were reluctant to provide him with the freedom and funds to do as he wished, necessitating a move to Suttgart, Germany. Working for Daimler-Benz, he eventually received widespread admiration and respect when the Mercedes he designed won the Targa Florio in 1924.

VW Beetle.

VW Beetle.

His other dream was to build an inexpensive vehicle for the German people. As the 1920s continued, he became increasingly convinced that a small vehicle for the everyday man would become an important part of the industrialisation and growth of his chosen country. Sadly for Porsche, his employers did not believe in this vision and he would work mainly on luxury cars for the next decade.

Adolf Hitler is known for many things, but his interest in automobiles is generally not one of them. He was poorly educated ? when reading books he would simply read the front and back chapters which meant he didn?t have an especially wide and deep range of knowledge. Cars, however, were something else, and he devoured as much on the subject as he could. Imprisoned in Landsburg prison for treason in 1923, he began to think of the car not just as a personal passion, but as a political tool, important and essential for the growth of Germany as a world power. He became obsessed with the idea of a small, inexpensive vehicle for the people. Much of this obsession came about due to his admiration for Henry Ford, inventor of the Model T in America. Hitler even had a poster of Ford in his office.

It took until the early 1930s for Hitler (now the Fhrer) to have enough power to carry out his plans at a state level. He sent his staff out to the various car manufacturers to investigate what was happening in the auto world. Word eventually made it to Porsche who travelled to meet the Fhrer at once. Hitler was enamoured with Porsche, his love for cars overcoming issues of politics. It was clear Hitler felt a kinship with the designer ? Porsche would become one of only a handful of men capable of speaking directly and without consequence to the dictator of Nazi Germany.

Hitler and Porsche.

Hitler and Porsche.

But still in the 1930s, before any public warning of war, Hitler wanted to turn his ideas for a small and affordable car into reality. He dictated to Porsche a number of rules by which the car must abide. It had to seat five people (two adults, three children). It had to cost no more than a motorbike. It had to be easy to repair. It had to be air-cooled, as most Germans did not have garages and radiators would freeze in winter. It is probable that Porsche already had all this in mind ? Hitler was well known for repeating others? ideas as his own. But with the funding and backing of the Nazis, Porsche finally began work on his People?s Car.

After several prototypes had been completed, Hitler decided to construct an immense factory and town in Wolfsburg to produce the new car. At an address in 1938, Hitler christened the new vehicle Kraft durch Freude-Wagen, or in English, the Strength Through Joy Car. Unfortunately, the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 meant the Wolfsburg factory (and the surrounding town) was not completed. It was initially not clear what would happen to the factory ? throughout the war it did build some war weapons (mostly vehicles for the army), but remained in a sort of limbo, with Hitler still half hoping it would produce Volkswagens.

When the war finished, the factory ended up in the hands of the British. The Allies were unsure of what to do with Germany, reluctant to let it become a world power again, but also aware of the mistakes made after the First World War. Britain was keen to revive some of Germany?s industrial strength, believing it to be an important part of restoring national pride. Major Ivan Hirst was put in charge of the Wolfsburg factory and was a firm believer in the Volkswagen. Working from a prototype he found tucked away, he began to instruct the workers to slowly reassemble the machinery that would build the vehicle.

The Nazis had tested the car extensively, but for political reasons parts such as the brakes, were not as good as they could have been (the best brakes were made in Britain). Hirst fixed many of these internal issues while keeping the original Porsche designed exterior. Locked away in a French prison for war crimes, Porsche himself had no further part in the running of the factory. He eventually returned in 1949 and saw his dream of a small car finally being realised. Porsche died in 1951 at the age of 75.

The Volkswagen was beginning to sell extensively throughout Europe during the 1950s as laws regulating exports from Germany were relaxed. The car was becoming popular. Through word of mouth advertising, the Volkswagen was even selling in America to those who weren?t convinced by the stylish and expensive offerings from Chevrolet and Oldsmobile. With sales of 100,000 Volkswagens in 1958, the major manufacturers could no longer ignore the market for small cars and were gearing up to release their own. To tackle this incoming threat Volkswagen sent a man named Carl Hahn to America. His job was to do something that Volkwagen hadn?t really done before ? advertise.

Changing Perceptions

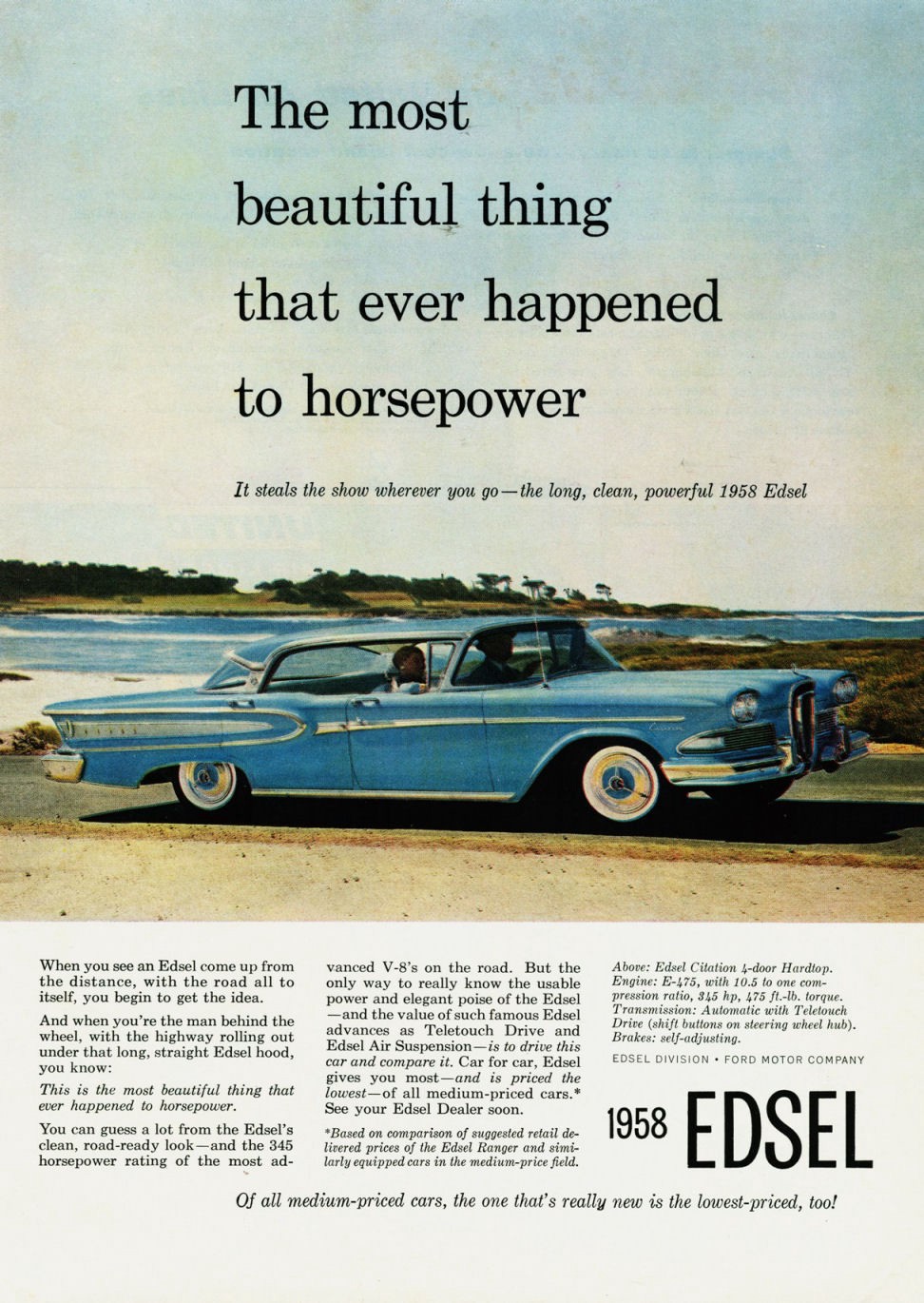

An campaign for the Edsel using a three column layout.

An campaign for the Edsel using a three column layout.

Carl Hahn visited many agencies on Madison Avenue and was disappointed with most of what they were showing him. The majority of companies, eager to impress, had done plenty of spec work showing an illustration of the car on a beautiful driveway with a nice family standing admiringly around it. Hahn was less than impressed with the mediocrity the agencies were showing him. Through a contact, he ended up at the offices of DDB and got a pitch from Bill Bernbach. Bernbach hadn?t done any mockups, drawings and had no concept for the ads he would run, his argument being that he didn?t know the product very well. Instead, he took Hahn through DDB?s portfolio of past works. What struck Hahn most about Bernbach was his honesty . At last, he felt he had found an agency capable of handling the car. The contracts were signed; Volkswagen would pay DDB $600,000, a minuscule figure compared to the ad spend of the other major manufacturers. In 1956, Chevrolet alone was spending $30.4 million on advertising, with Ford following at $25 million. A really good campaign was needed to compete.

Carl Hahn immediately invited the DDB team over to Germany to see the factory in action. Bernbach was very impressed with what he saw, especially with the pride the workers took in their craft. He remarked to another DDB man named Helmut Krone that this was an ?honest car?.

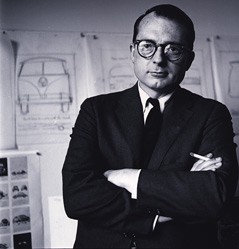

Helmut Krone

Helmut Krone

Helmut Krone was born in New York in 1925, shortly after his parents had emigrated from Germany. As a young man, he was prompted to enter print advertising when he saw the work of Paul Rand. He later joined DDB as an art director. Krone was described by his colleagues as ?a complex kraut? and ?a fidgety perfectionist who worked with deadly Teutonic patience?. The simple layouts he designed didn?t betray the countless hours agonising over tiny details. DDB was actually already promoting the Volkswagen for a local car dealer. Krone was working on that campaign, so it was only natural that he was given the main account. He also personally owned a Volkswagen. Like all the teams at DDB, Krone (the art director) worked alongside a copywriter, in this case a Jewish man who wasn?t bothered with the Nazi connections.

Julian Koenig was born in 1921, also in New York City. He had an on-off relationship with advertising, feeling frustrated at the lack of creativity he was permitted to express in his writing. After a brief stint as a professional horse better, he joined DDB as a copywriter in 1958. Working with Helmut Krone was apparently a challenge. Krone was unhappy with the honest approach Bernbach wanted to take. He initially wanted to present the car the way the other agencies had intended to ? make the car as American as possible. Krone was also uncomfortable with the idea of selling ?the Fhrer?s car?.

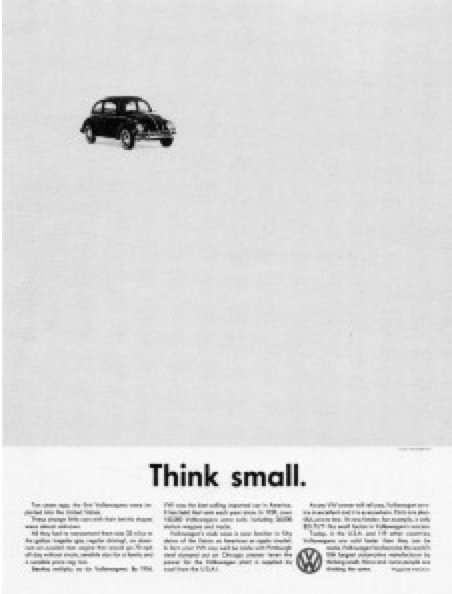

The original 1959 Think Small ad. Note the angle of the car.

The original 1959 Think Small ad. Note the angle of the car.

It was when the client, advertising manager Helmut Schmitz read Koenig?s copy that he noticed a small line. The copy went ?maybe we got so big because we thought small?. Schmitz pointed at ?think small? and said that was to be the headline. Koenig was pleased with this ? his original headline had actually been ?Think Small? but he?d been talked out of it by Krone who had wanted ?Willkommen?.

The art director was very unhappy with this development, and it took an intervention by Bernbach to persuade him to come up with some layouts. After much experimentation, Krone settled on a traditional ad layout, with an untraditional image. The headline and three column body was a traditional format used in a lot of advertising ? Krone jokingly called it ?The Olgivy Layout?, Olgivy being an agency Krone felt was creatively inferior. Part of the genius Krone possessed was the ability to take something familiar and alter it just enough to make it new.

This included setting the heading and body text in a sans-serif typeface, Futura. Most copy up until this time had been set in serif typefaces. Widows and orphans were everywhere. Krone actually cut them into the original ad with a razor blade ? he was deliberately going for a halting and natural quality. He even instructed Koenig to write the copy in this way. The result of all these widows and orphans is an imperfection and honesty that couldn?t be achieved with a more ?professional? look. The quirky typesetting perfectly complemented the personality that Koenig gave his writing. A full stop was placed at the end of the headline, forcing the reader to stop and think about what they had just read. Putting a full stop after headlines would eventually become a trademark for Krone.

Then there?s the Volkswagen logo, set awkwardly between the second and third columns. Krone hated using logos in his ads. Some of his other well known campaigns such as those for Avis didn?t even have a logo. But by putting the Volkswagen logo where the reader didn?t expect it meant this did not feel like a normal ad. Finally, there?s the car. Krone settled on using a photo of the vehicle, not a fancy illustration like everyone else was doing. It is placed in the upper left corner, on a slight angle and in an ocean of white space.

The entire ad was printed in black and white, mainly because Volkswagen didn?t have enough money to print it in colour. This created a very striking effect when it was viewed next to all the other colourful pages in Life Magazine, where it first appeared for consumers. Everything about the ad screams honesty and simplicity.

Krone hated the ad he?d put together. In fact, he hated it so much he deliberately left the country when it was first published. Expecting a hailstorm of criticism on his return, Krone found himself being praised for his work, although Koenig said it was only later that the Think Small ad became famous.

At the time, the advert was viewed with suspicion by those on Madison Avenue. The public, however, had a different reaction. People talked about it around the water cooler. Teenagers ripped it out of magazines and pinned it to their walls. It became, temporarily, more than just another ad. The sales figures backed up the approach when DDB learned about the sales impacts the ads were having.

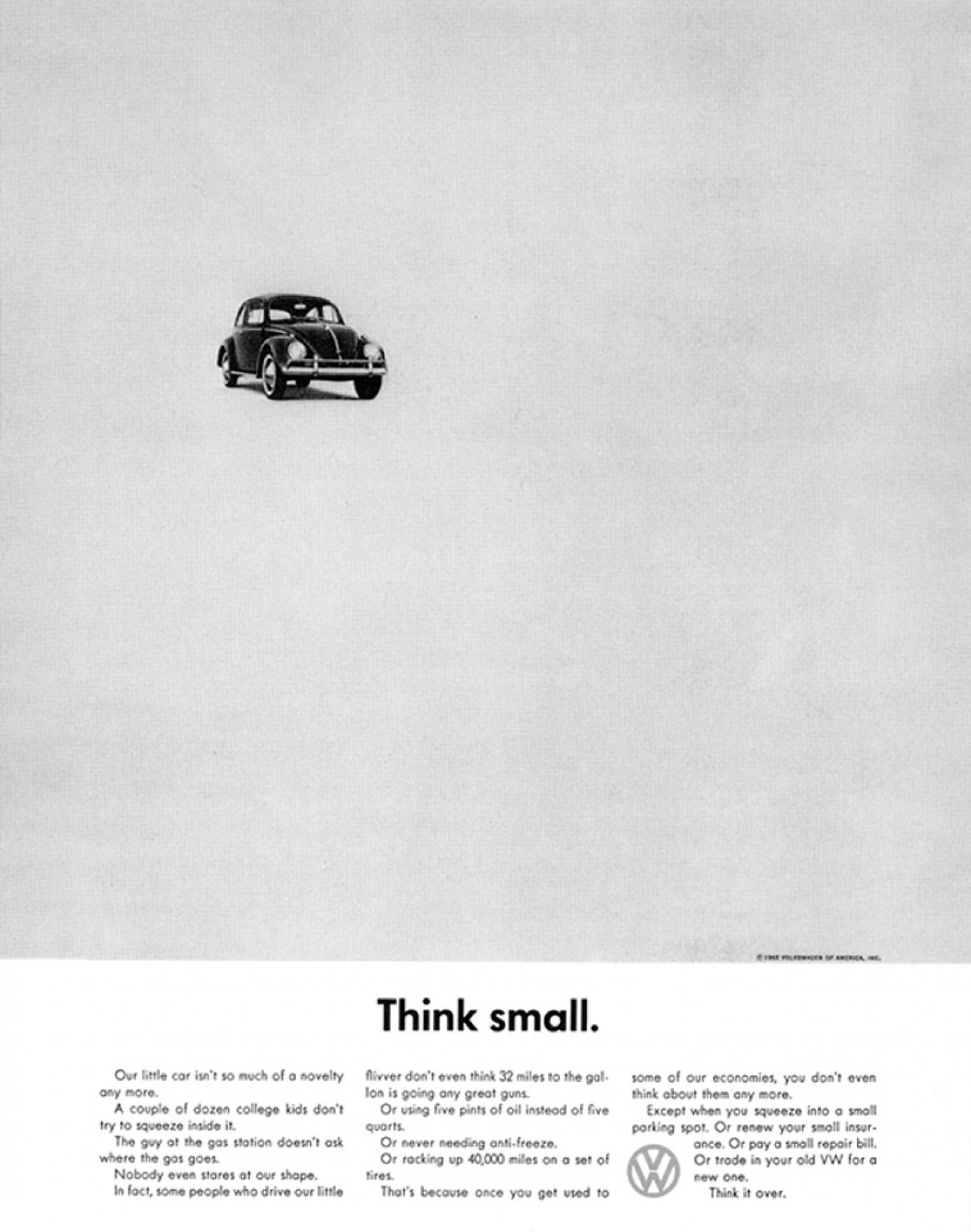

The 1960 version of Think Small, with a refined version of the car.

The 1960 version of Think Small, with a refined version of the car.

Julian Koenig left DDB in 1959 to start his own agency and Helmut Krone was paired with another copywriter, Bob Levenson. Levenson rewrote the Think Small copy and the ad was released again in 1960 with a few artistic changes by Krone. Levenson understood that the new approach to the Volkswagen campaign required a new tone of voice, more than perhaps Koenig had. He understood that the copy had to look visually great as well as telling a compelling story in a self-deprecating and intelligent way.

The Impact

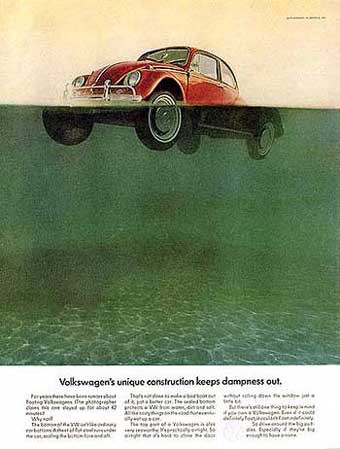

Together, Krone and Levenson would continue the Volkswagen campaign and keep pushing boundaries. There was the ?51 ?52 ?53 ?54 ?55 ?56 ?57 ?58 ?59 ?60 ?61 Volkswagen ad which demonstrated how the car?s appearance never changed, giving customers relief from the pressure to have the latest. Krone kept coming up with inventive ways of showing the car, such as it floating on water (to demonstrate the quality of its welds) or with its front smashed in (to show how easy it was to repair). Krone even went as far to not show the car at all (again to show the design doesn?t change).

Other versions of the Volkswagen campaign.

Other versions of the Volkswagen campaign.

Over the years, the layout of the ads became an integral part of the Volkswagen campaign and a recognisable part of the brand. One memorable example of this was in 1969, with a photo of a model Lunar Module. The headline reads ?It?s Ugly But It Gets You There? with a small Volkswagen logo. The logo almost isn?t needed, the layout had become so familiar at this stage.

In fact, Volkswagen advertising today still uses a similar layout to those first created by Helmut Krone. DDB still manages the Volkswagen account.

As part of a cultural shift, the Think Small ad and the ones that followed marked a true shift in the advertising landscape. The customer was trusted to be smart enough to work things out since the copy didn?t speak down to anyone. Suddenly there was an ad that appealed to people?s intelligence in a way that the style based campaigns of the past had not. Honesty as a selling point had never really been tried before, at least on a major campaign such as for a large car manufacturer.

The ad tapped into a sense of disconnect that the public was feeling as a result of being pressured to buy and consume for so many years. This was especially felt by younger people. Those born after the Second World War saw their parents encouraged to buy and consume their way to happiness and they rejected this (to a large degree). The Think Small campaign was created just as this voice was starting to make its presence heard ? it would be heard loudly throughout the sixties. The Volkswagen Beetle became an integral part of the counter culture in America, helped in large part by the highly effective advertising DDB kept producing.

The influence of Think Small is still seen today. People like Bill Bernbach, Helmut Krone and Julian Koenig are seen as pioneers of the Creative Revolution. Stylistically the ad started a shift from illustrations toward a greater use of photography. The crisp sans-serifs would be used in the corporate identities of later decades. Copywriters would not just explain product features any longer, suddenly tone of voice became an important part of their job.

Perhaps most importantly was that it showed ad agencies they could still sell products in a creative way and didn?t have to rely on the ?textbook?.

Bernbach?s belief that ?good taste, good art and good writing? could be good selling was proved.

Published in The Agency- Creativity, Innovation, and Ideas for the modern Agency. Follow us here! Curated by Crew.

Several books were invaluable in preparing this article. I highly recommend them to people interested in this subject:

Cracknell, Andrew. The Real Mad Men: The Remarkable True Story of Madison Avenue?s Golden Age. London: Quercus, 2011. Print.

Fox, Stephen R. The Mirror Makers: A History of American Advertising and Its Creators. United States: University of Illinois Press, 1984. Google Books.

Heimann, Jim, ed. All-American Ads: 50s. Kln: Taschen, 2001. Print.

Note: The ads in the All-American Ads book are truly fantastic.

Hiott, Andrea. Thinking Small: The Long Strange Trip of the Volkswagen Beetle. New York: Ballantine Books, 2012. Print.

I highly recommend Andrea Hiott?s book as it is an excellent overview of what was happening around that time.

Imseng, Dominik. Think Small: The Story of the World?s Greatest Ad. Full Stop Press, 2014. iBook file.

Meggs, Phillip B and Alstron W. Purvis. Meggs History of Graphic Design (5th ed.). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2012. Print.

Sullivan, Luke. Hey Whipple, Squeeze This. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc, 2008. Print.

Web References

Cooke, Marty. ?Was Helmut Krone a Genius??. Advertising Age Online. Web. 29 March 1999. <http://adage.com/article/news/helmut-krone-a-genius-a-copywriter-toiled-alongside-legendary-art-director-begs-differ-employing-wit-disarm-audience-turning-a-page-helmut-proved-simply/62928/>.

Garfield, Bob. ?Ad Age Advertising Century: The Top 100 Campaigns?. Advertising Age Online. Web. 29 March 1999. <http://adage.com/article/special-report-the-advertising-century/ad-age-advertising-century-top-100-campaigns/140918/>

Ries, Al. ?Advertising Could Do With More of Bernbach?s Genius?. Advertising Age Online. Web. 6 July 2009. <http://adage.com/article/al-ries/advertising-bernbach-s-genius/137740/>

Image References

Front Image: ?Third Think Small Volkswagen Ad Revision 1960.? Digital File http://visual.ly/communication-design-blog-6-6-10-6-

?Clark Stanley?s Snake Oil.? Digital File.http://www.thewire.com/business/2012/01/groupon-criticized-literally-peddling-snake-oil/47851/

Cracknell, Andrew. ?Anacin Asprin.? The Real Mad Men: The Remarkable True Story of Madison Avenue?s Golden Age. London: Quercus, 2011. Print.

Figure 3: Heimann, Jim, ed. ?Plymouth Ad.? All-American Ads: 50s. Kln: Taschen, 2001. Print.

?Bill Bernbach Portrait.? Digital File. http://www.rhinowrites.com/wprw/?p=379

?Ferdinand Porsche Portrait.? Digital File. http://www.fansshare.com/community/uploads21/21083/ferdinand_porsche/

?Volkswagen car.? Digital File. http://pixabay.com/en/vw-beetle-auto-classic-oldtimer-233935/

?Hitler and Porsche.? Digital File.http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20130830-the-nazi-car-we-came-to-love

?Edsel Citation 4 Hardtop ad 1958.? Digital File. https://www.flickr.com/photos/aussiefordadverts/9447821193/in/pool-1528445@N20

?Helmut Krone Portrait.? Digital File. < http://www.enchorial.com

?Original 1959 Think Small Volkswagen Ad.? Digital File. Imseng, Dominik. Think Small: The Story of the World?s Greatest Ad. Full Stop Press, 2014. iBook file.

Figure 10: ?Third Think Small Volkswagen Ad Revision 1960.? Digital File. http://visual.ly/communication-design-blog-6-6-10-6-

?Volkswagen?s unique contruction keeps dampness out.? Digital File. http://www.aden.co.jp/page_works/vw/VW_ad/ad04_1.html

?Volkswagen Apollo.? Digital File. http://volkswagen-auto.net/apollo/generac-generators-at-the-best-money-saving-deals.html

Published in The Agency- curated by Crew. Check us out to get started working with the best designers and developers on the web.Over 10 million people have used products made on Crew. And over 3 million people have read our blog. Join them here.