?Look, you?re already dead. If you?ll just quit fighting, I?ll make it easy for you.?

As crimson blood spread over a bright, white snowbank, survivors knew McCarthy would never be the same again.

Most Alaskans are adventurous, self-sufficient individuals who can survive on their own but are willing to lend a helping hand to others. A few people, though, come to Alaska to escape their problems or to hide from the law. Usually, they bring their problems with them.

I live in the wilderness on Kodiak Island in Alaska, where my husband and I own a remote lodge, and the story I am about to tell you reflects my worst nightmare. I live in the midst of the world?s most concentrated population of huge brown bears, but bears are not what scares me most. There are no roads or cars where I live, and no other human habitations within miles of my home, so the most frightening thing I can imagine would be to look out a window on a stormy, winter night and catch a glimpse of a human shadow running across the walk.

A few times, hunters in need of our help have knocked on our door late at night, and while we were happy to assist them, I realized there was no one we could call for help if the visitors threatened us. The Alaska State Troopers are the responsible law-enforcement agents outside the Kodiak city limits, but they are based in the town of Kodiak, 70 air miles from my home, and they can only respond during daylight hours because it is not safe to fly over this mountainous island at night. We are on our own if some psychopath forces his way into our lives.

Like the folks in the story I am about to tell you, a plane carrying our mail, supplies, and groceries stops at our dock once a week, and eerily enough, our mail plane, like the plane that serviced the doomed residents of McCarthy, is also on Tuesday. Since the plane lands and pulls up to our dock, we are sometimes the only people here to meet it, but anyone can get supplies and mail or pay for a seat fare on this plane. Occasionally, people we?ve never met show up for the plane to wait for supplies and passengers, and we invite these strangers into our home for coffee and cookies while they wait for the plane. Usually, these folks are nice and appreciate our hospitality, but once in a while, someone makes me uncomfortable, and I breathe a sigh of relief when I see him speed away from our dock in his boat, heading back toward his campsite. We know nothing about these strangers, but we assume and hope they mean us no harm.

The folks in McCarthy, Alaska probably also felt safe around the neighbors and strangers who showed up to wait for their mail plane. The people who lived in the wilderness near McCarthy were bound together by their chosen lifestyle. They enjoyed their solitary lives, but each week they looked forward to gathering with their neighbors and socializing for an hour or two while they waited for the mail plane to arrive. Everything changed on that fateful day in 1983. Mail day would never be the same again.

***

In 1983, Les and Flo Hegland?s home in McCarthy, Alaska was the gathering spot where the 22 residents of the Kennicott/McCarthy area waited for the weekly mail plane. The Heglands lived near the small airstrip where the plane landed, and not only did they offer their hospitality, but they even built an addition onto their front porch, where they left uncollected mail and groceries so nearby residents could drop by at their convenience to pick up their freight. The Heglands owned the only two-way radio in the area strong enough to communicate with the outside world, and they relayed daily weather reports to the Federal Aviation Administration office in Cordova. The Hegland house was more than just a place for residents to sit and wait for the plane to arrive. Except for the mail plane pilot, the Heglands were the McCarthy residents? lone link to civilization. Tuesday, March 1st, 1983 was mail day.

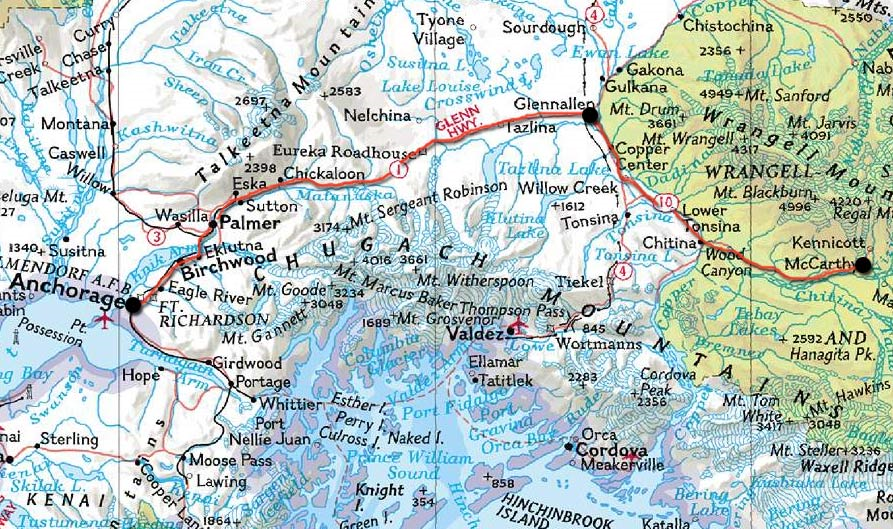

McCarthy and Kennicott are located four miles from each other in the middle of the Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, approximately 120 miles (193 km) northeast of Cordova, and 230 miles (370 km) east of Anchorage. Wrangell-St. Elias encompasses an area about the size of West Virginia, with four mountain ranges converging in the park. The temperature fluctuates from 50 degrees below zero (-45.?? C) in the winter to 90 degrees (32.? C) in the summer. The annual snowfall averages 52 inches (132 cm).

At the turn of the 20th century, the richest concentration of copper ever mined was discovered in the mountains above Kennicott. The town of Kennicott was developed as a place for the miners to live while McCarthy was developed as a place for the miners to play. By the 1930?s, most of the ore was gone, and Kennicott and McCarthy became ghost towns. The railroad track that had been used to transport the ore soon fell into disrepair and became the McCarthy road. This road begins where the pavement ends in Chitina, sixty-one miles (98.2 km) to the west, and by 1983, the road was nearly impassable.

Residents of the area were mostly stranded during the long winter of 1983, and they were dependent upon and looked forward to their Tuesday mail plane. In 1983, McCarthy had no running water, no telephones, and no electricity, except for the power provided by individual generators. The independent souls who called this remote area home had little contact with the outside world, so the weekly gathering to wait for the mail plane was a way to share news.

On February 28th, the night before mail day, in Kennicott, four miles north of the McCarthy airstrip, 29-year old Chris Richards played a board game with his neighbor, 39-year old Louis Hastings, an unemployed computer programmer who had moved to Alaska from California in 1980 and had only lived in the Kennicott area for a year. According to Richards, the evening was unremarkable, just a friendly game between two neighbors.

The following morning as Richards cooked breakfast, Hastings again appeared at his front door. Richards assumed Hastings was on his way to meet the mail plane, and he pushed open the door and invited Hastings in for coffee. Richards then turned his back to the door while he continued cooking his meal.

A moment later, Richards felt something strike his right cheek, shattering his glasses. He immediately ducked his head and then felt an object hit his head. He turned toward Hastings and saw the other man walking toward him with his rifle held high, ready to fire again. Richards grabbed Hastings, and they began to struggle while Richards screamed at Hastings to stop shooting.

Hastings said, ?Look, you?re already dead. If you?ll just quit fighting, I?ll make it easy for you.? Richards fumbled for a knife from the sink and stabbed Hastings in the left, upper chest and the right leg. Richards then fled the cabin into the waist-deep snow, wearing only socks, one slipper, a T-shirt, and light corduroy pants. The temperature in Kennicott that morning was 10 F (-17.2 C).

While Hastings fired shots at him, Richards fought his way three-quarters of a mile (1.2 km) up a steep hill to an unoccupied cabin, where he found boots, a parka, and snowshoes. He then staggered one-tenth of a mile (161 m) to the southwest to the cabin of Tim and Amy Nash.

The Nashes were a young couple who had just gotten married on Christmas day, and after a long honeymoon, they had only returned to the Kennicott area two weeks earlier. Tim and Amy bandaged Richards? wounds while he told them what had happened. Since Hastings appeared to be on his way to McCarthy where area residents would soon be gathering to meet the mail plane, Richards and the Nashes decided to arm themselves and head to the runway and to the Hegland?s home to warn the others about Hastings.

Meanwhile, 52-year-old Maxine Edwards left her husband at home while she crossed the frozen Kennicott River and proceeded to the Hegland?s house to await the mail plane. Flo Hegland, 58, and Les, 64, had lived in McCarthy since 1967 and were considered the unofficial postmasters by area residents. The Heglands were the heart of McCarthy, and they provided a foundation for the independent loners who called the area home. If an area resident wanted to send a message to a friend or relative, or if a relative needed to contact one of the McCarthy residents with an urgent message, it was the Heglands who sent and received these communications on their side-band radio. The Heglands and their home were central to the loosely knit community of residents within a fifty-mile radius of McCarthy.

Back at their home in Kennicott, the Nashes bundled Richards onto a sled and towed it behind their snow machine as they sped toward McCarthy and the airstrip. When they reached the airstrip, they met Gary Green, a pilot and guide. Green was cleaning off his airplane, and when he heard their story, he told them he had seen Hastings twenty minutes earlier heading toward the Heglands? house. Tim Nash volunteered to check on the Heglands, while Green warmed up his plane in preparation to fly Richards to Glenallen, forty minutes away, for medical care. Green said he would contact the troopers and request their assistance.

As Green was loading Richards into the plane, Amy Nash saw her husband running down the airstrip toward them. He had just been to the Hegland?s house, where he?d smelled the acrid aroma of gunsmoke and had seen blood splattered over the interior of the house. Tim believed the Heglands were dead and said when he walked into the kitchen, he saw Hastings standing on the back porch. Nash fired at Hastings and missed, but when Hastings returned fire, he struck Nash in the right leg. The Nashes told Green to go for help, and then they made the fateful decision to stay at the airstrip to warn the others.

Once Green took off, he radioed the incoming mail plane and told the pilot not to land at McCarthy. He then contacted the Alaska State Troopers in Glenallen and reported the situation.

While Tim and Amy waited in the freezing morning air, Hastings followed a dog sled trail through thick brush back to the airstrip. He crawled up a large mound of plowed snow across the runway from the Nashes and fired ten rounds at the newlyweds who stood two-hundred-and-fifty yards (228.6 m) away from him. He then walked to within fifty feet (15.24 m) of their bodies and fired two more shots and then continued to approach, firing two final shots into their heads. He dragged their bodies to the top of the snowbank across the runway from where they had died in an attempt to hide them in deeper snow.

Soon after Hastings climbed the snow bank, two more area residents, Harley King and Donna Byram, arrived at the north end of the airstrip on King?s snow machine. Harley King, 61, and his wife, Jo, had lived on their homestead 15 miles west of McCarthy since 1966. Jo, a well-known bush pilot and flight instructor had flown her plane to Anchorage and was waiting for the weather to improve before flying back to McCarthy, so she was not home that fateful day, but her husband had agreed to give Donna Byram, 32, a ride to the airstrip. Byram, who lived between the Kings? home and McCarthy, was planning to fly out on the mail plane.

Byram saw large blotches of blood on the snow-covered airstrip and then spotted Hastings standing on the snowbank. When they drew closer, Hastings opened fire on them. Byram was standing on the sled behind the snow machine, and she saw bullets hit the machine and King. One bullet hit Byram in the upper right arm. King drove the snow machine as fast as he could toward the south, away from Hastings, but one of Hasting?s shots had broken his leg, and he soon lost control. The snow machine crashed and threw King and Byram to the runway near the path leading to the Heglands? home.

Byram tried to load King back onto the sled, but Hastings was quickly approaching. King told her he couldn?t move and urged her to save herself. After a moment?s hesitation, Byram fled toward the Heglands? home. As she ran, she heard two shots and knew King was dead. When she reached the Heglands? house, she saw the front door had been kicked in, so she ran to the greenhouse and hid outside. As she huddled, shivering, she heard Hastings approach, calling out, ?One not dead. One not dead.? She held her injured arm and fought to stay quiet, certain she was about to die. She heard Hastings? footsteps on the porch and knew he would soon find her, but then he abruptly turned around and sped off on the Nashes? snow machine.

Hastings headed west on the McCarthy road, where the troopers from Glennallen easily intercepted him by helicopter. Hastings waved to the troopers when they landed and told them he was Chris Richards and explained that Lou Hastings had gone berserk and was shooting up McCarthy. The troopers knew Richards was already in Glenallen, though, and this man fit the description of Lou Hastings. They arrested Hastings without incident.

With Hastings handcuffed and restrained in the helicopter, the troopers continued to McCarthy where they found the bodies of Tim and Amy Nash and Harley King on the runway. They were all dead from gunshot wounds, with final kill shots to each of their heads. Inside the Heglands? house, the troopers discovered the bodies of Les and Flo Hegland and their neighbor, Maxine Edwards, stacked in the bedroom. A bloody fur-covered silencer sat on the nightstand beside the bodies.

Troopers found the injured Byram outside the greenhouse and helped her to the helicopter. She was forced to share the ride to Glenallen with the man who had murdered her neighbors and had tried to kill her.

Why did Louis Hastings go on a murderous rampage and kill his neighbors? The reason is nearly as bizarre as the crimes themselves. Hastings was an intelligent computer programmer who had worked at Stanford University in the late 1970s, but like many people who move to Alaska, he left the overdeveloped area where he lived in California with dreams of starting a new life in the unspoiled wilderness of Alaska. At first, he and his wife settled in Anchorage, and he started a computer-service business out of his house, but by 1982, his business and marriage had failed, and he began to spend more and more time at his cabin in Kennicott. Alaska?s economy was booming in 1983 due to the construction of the trans-Alaska oil pipeline that carries oil from Prudhoe Bay south to the port of Valdez on Prince William Sound. The state was flush with money and in the midst of a construction boom. Hastings hated the pipeline and related development it had created, and he felt the state?s newfound prosperity would ruin the lifestyle he had dreamed of when he?d moved to Alaska. It became his mission to destroy the pipeline.

Hastings finally divulged his convoluted scheme to authorities. He had planned to arrive in McCarthy before the mail plane and kill anyone who showed up to meet the Tuesday plane. Next, he would kill the mail plane pilot and steal the plane. He then planned to fly to a pump station near the pipeline about eighty miles (128.7 km) west of McCarthy, where he would land and rig the plane to take off again without him in it. Then, he planned to steal a fuel truck and ram the pipeline while shooting at it. This action, he believed, would badly damage the pipeline, but he hoped the oil would congeal in the cold winter temperature and not do too much environmental damage. After rupturing the pipeline, he then believed the fuel truck would burst into flames and char his body beyond recognition. He hoped people would think he had been murdered in McCarthy with the other residents, and his family would never know he was a murderer who had committed suicide in the end.

Louis Hastings brutally massacred six people on March 1st, 1983 because he believed murdering his neighbors was a necessary first step in his brilliant plan to preserve the Alaskan wilderness. Les and Flo Hegland, Maxine Edwards, Tim and Amy Nash, and Harley King died in the McCarthy massacre, and Chris Richards and Donna Byram were injured.

As a sad footnote to this tragic story, Chris Richards, a man the surviving residents of McCarthy considered a hero because his swift actions had saved more people from being killed in the 1983 massacre, died when his Kennicott cabin burned down one week before Christmas in 2001. After his death, many who knew Richards said Hastings had finally claimed his seventh victim. Richards never recovered physically or mentally from the massacre, and in later years, survivor?s guilt, depression, and alcoholism plagued him. According to those who knew him, at the time of his death, he was trying to give up alcohol and was suffering from hallucinations.

The McCarthy/Kennicott area is now a popular tourist destination, but like most remote areas in Alaska, the crowds leave in September, and only a few, hardy individuals choose to live in such a desolate wilderness in the winter. Most of these people cherish their solitude, but they often must depend on each other to survive the long, cold winter. For the folks of the McCarthy area, it was not easy for them to trust their neighbors again after that horrible Tuesday in March 1983, and mail day has never been the same since.

Sign up below for my free, monthly newsletter about murder and mystery in Alaska.