Welcome to Vidor, a town most famous for its racism

A welcome sign for my hometown that sits alongside I-10. (Michael Corcoran )

A welcome sign for my hometown that sits alongside I-10. (Michael Corcoran )

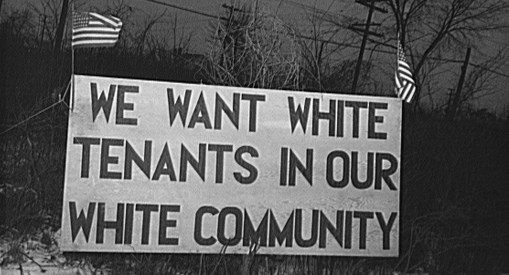

A sign that was placed outside the Sojourner Truth Homes, a Michigan housing project, in 1942. A half century later Vidor had its own battle over the plan to integrate its housing projects ( Truman Historical Library / Wikimedia Commons)

A sign that was placed outside the Sojourner Truth Homes, a Michigan housing project, in 1942. A half century later Vidor had its own battle over the plan to integrate its housing projects ( Truman Historical Library / Wikimedia Commons)

The generic sundown town sign was a formal, simple statement of policy, like ?No parking after 5 p.m.? Vidor?s sign was not. According to legend, the sign said in big, painted letters:

?N***er, don?t let the sun set on your black ass!?

Not that the sign was really necessary; Vidor?s reputation was deterrent enough. If you were a black man traveling through town in the bad old days and you got a flat, the smart move would be to ride on a rim until you reached the city limit sign.

In an interview with CNN, a 62-year-old man from Beaumont recalled an incident that happened when he was a teen in the 1970s. He and his friends were changing a tire in Vidor when a white policeman threatened them. According to the CNN story, “[The white policeman] said, ‘Well, let me tell ya ? you boys better wrap and get out of here, because I’m going to go to that next exit and come back around. You better be gone!? “

In the same story, the reporter talked to a county official who claimed there ?hasn?t been a Klan here in 30 years.?

Anyone who?s lived in Vidor knows this is a lie.

Here comes Klanta Klaus

My hometown had all the usual fraternal clubs one might expect: Kiwanis, the Masons, the Evening Optimists, the Elks, and the Rotary Club. But it also had the Klan. However, the ?Invisible Empire? largely stayed true to their name.

I?ve heard that, during the decade before I was born, the Klan was much more brazen about the whole thing. There are apocryphal stories about roadside cross burnings, signs that said ?Klan Kountry,? and even a KKK bookstore on Main Street.

I can?t personally attest to any of that. I never witnessed a single burned cross, but I did occasionally run across Klansmen in full regalia.

Once, when we were making our weekly pilgrimage from church to the mediocre Mexican place in town, I looked out the window and there they were. About a dozen Klansmen in hoods were just standing there on the side of the road holding signs that said ?Be a Man. Join the Klan.? next to a yellow school bus. One was dangling a banana from a cane fishing pole.

I?ll leave you to figure out the symbolism on that one.

When I was about 17, I randomly met a kid who was apparently the scion of some local Klan big shot. My friend and I were at a Halloween party by the river in the ?peckerwood? section of North Vidor. Oddly enough, there was a black kid there, too, but he didn?t stay for long.

Around Christmastime, jolly old Klanta Klaus made an appearance at his junior high basketball game to bring cheer to all the good little white girls and boys.

The Klansman?s son, who was around 12, was the younger brother of the guy hosting the party. He thought it would be funny to give his black guest a scare by dressing up in a Klan getup that he just happened to have lying around. It wasn?t a normal white robe or a bed sheet with holes cut in it. It was well made and green, like the leaders wear.

The black kid hightailed it out of there, after which the little bastard popped his hood off and they all died laughing.

The weirdest incident happened to my brother. Around Christmastime, jolly old Klanta Klaus made an appearance at his junior high basketball game to bring cheer to all the good little white girls and boys.

Most of the time, the Klansmen kept a pretty low profile. But you couldn?t live in a town that small and not see signs of them around. Their home base was Gary?s Coffee Shop, a 24-hour diner on Main next to the highway. The bathrooms were covered in Klan graffiti scrawled in childish chicken scratch.

My friends and I would go there at 2 a.m. to chain smoke and drink bottomless cups of bad coffee. I can?t say I ever overheard a Grand Kleagle talking Klan business with a Most Exalted Warlock, but I did find one of their business cards on a table once. It listed the phone number and address of their Klavern 20 miles up the road over in Mauriceville, where my Uncle Boyce has his crawdad farm.

And when I say that they where mostly inconspicuous, there is one notable exception: In the early ?90s, they made their presence known in a big way, and the whole country took notice.

Jim Crow rides again

When I was still in middle school, Vidor became a battleground for the kind of fight that hadn?t been seen since the Civil Rights movement. The tiny town was thrust into the national spotlight after an attempt to integrate its all-white housing projects met resistance from locals as well as Klan groups from around the state.

A battle over integration raged for more than a year starting in the fall of 1992. Housing authorities announced that they planned to move black families in, prompting a mass Klan demonstration at the county courthouse in Orange as well as several smaller marches and rallies in Vidor itself.

The KKK rallies in a pavilion at the same park where Vidor hosts its annual BBQ Festival (Screencap from ?The Least of My Brothers? / Matthew Kordelski / Youtube)

The KKK rallies in a pavilion at the same park where Vidor hosts its annual BBQ Festival (Screencap from ?The Least of My Brothers? / Matthew Kordelski / Youtube)

Mayor Ruth Woods claimed the KKK were outsiders. Many were, but they also had plenty of local allies and sympathizers. In the documentary The Least of My Brothers, the leader of the Knights of the White Camelia (WCK), who was from a town an hour west of Vidor, said they were called in by ?people [they] knew.?

The following year, in February, two black men moved into the projects and stayed for six months. One of the men, Bill Simpson, whose friends in the projects and the local church recall as a ?gentle giant,? was murdered in a robbery shortly after returning to Beaumont.

That summer, the housing authorities tried again. They moved in two single black women with young children from Louisiana, thinking that they might get more sympathy. They were wrong.

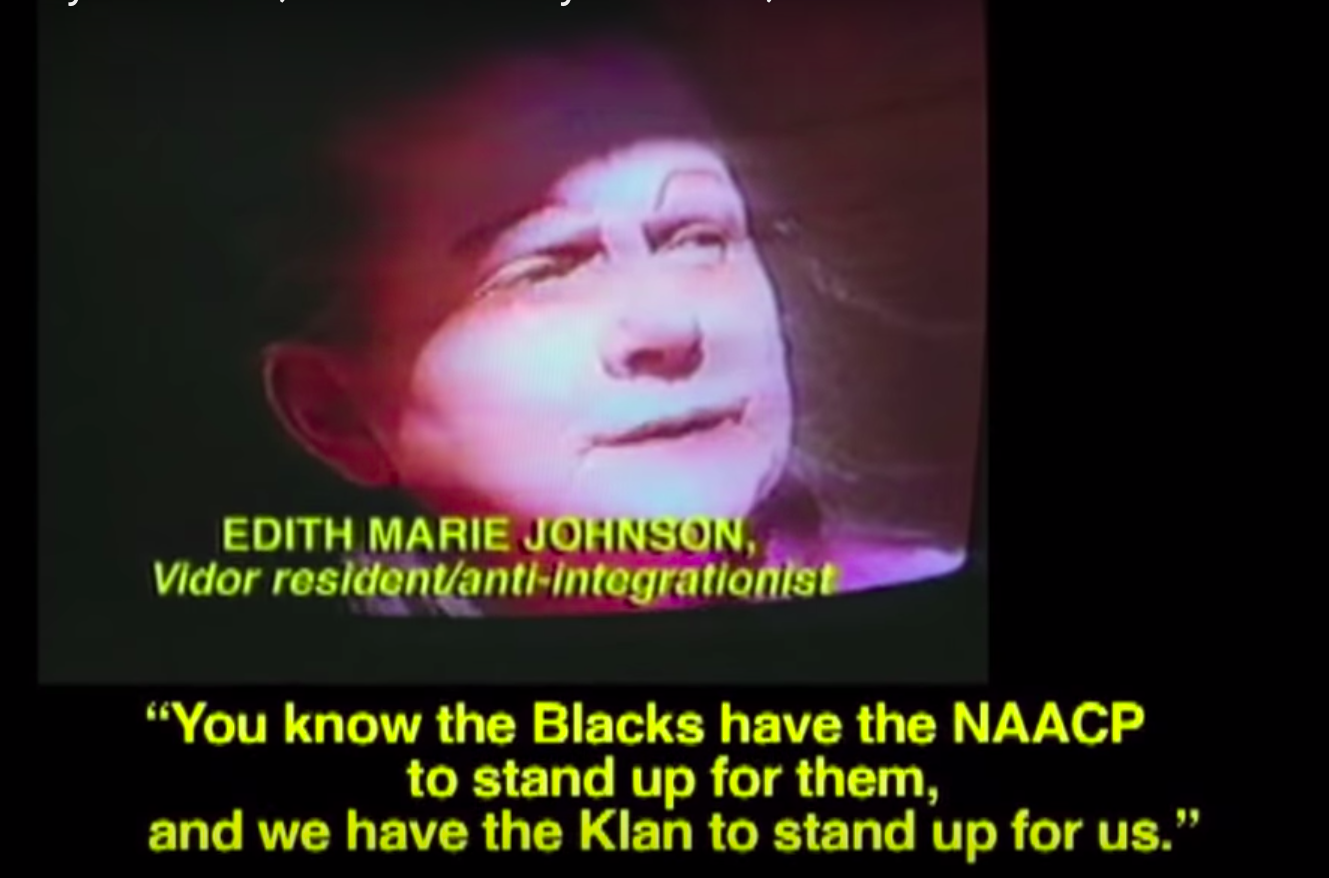

(Screencap from ?The Least of My Brothers? / Matthew Kordelski / Youtube)

(Screencap from ?The Least of My Brothers? / Matthew Kordelski / Youtube)

Quite a few in the housing projects welcomed their new neighbors, just as they had Bill Simpson. Others were considerably less than kind, such as Vidor Village resident Edith Marie Johnson.

Johnson brandished a baseball bat, which she threatened to use on both the women and their children as well as any of the ?n***er lovers? in the projects.

The Klan escalated its campaign of terror and intimidation. Charles Lee, the Grand Dragon of the WCK, offered a $50 bounty to white teens to beat up the black residents of the projects. They would drive past in a repurposed school bus with assault weapons poking out of it.

One Klan member, James Hall of Mauriceville, bragged that he had personally commissioned Simpson?s murder. He told residents that he had 500 pounds of explosives in a bus that he would use to blow the whole place sky high.

The women left after just two weeks.

In the fall, the President Clinton?s Dept. of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) under Henry Cisneros took direct control over the federally-subsidized projects, evoking many of the themes of the 1960s. The Klan billed itself as the white David taking on the federal Goliath.

The government tried again in January of 1994, moving in four families under the cover of darkness while U.S. marshals provided protection. A year later, one family had already moved out and two more were planning to. They faced the same threats and harassment as those before them.

A teen was arrested on a charge of misdemeanor terrorist threat for wielding a knife and telling one of the women he was going to gut her and her ?ni***er babies.?

?The all-white town that keeps blacks out?

The more horrible aspects of this particular story were largely unknown to me at the time. After all, I was only about 11 when this went down. My parents didn?t take me to the rallies so I experienced the story in the same way everyone else did: through my television.

It was surreal to see my little one-horse town become the subject of a national media feeding frenzy. The whole thing made great fodder for the daytime talk shows that loved nothing more than trashy drama, and Klan stories were always hot.

Phil Donahue hosted a panel discussion with a Texas Klan leader, a black separatist, and for a dash of credibility, an actual county housing official. Not to be outdone, Montel Williams did an episode live from the Julie Rogers Theater in Beaumont titled ?The All-White Town That Keeps Blacks Out.? The only thing I remember about the episode was that a Klan supporter in the audience was wearing a Lone Star Feed cap, advertising the feed store up the road from my house.

(Screencap from ?The Least of My Brothers? / Matthew Kordelski / Youtube)

(Screencap from ?The Least of My Brothers? / Matthew Kordelski / Youtube)

What I remember most vividly from that time, though, was the episode of A Current Affair titled ?The Most Hateful Town in America,? wherein they sent a black man with a hidden camera to town.

They actually didn?t get much this way. Someone yelled a slur at him while driving by, but when he went to a local church, he was received quite warmly by the congregation.

Their mistake, most likely, was sending him to one of the fancier, more civilized churches. For the good dirt, they should have had him visit the backwoods variety for folks who do their praying in an aluminum building.

Based on my own experience, the episode also didn?t necessarily mean that everyone at the church was thrilled about him being there. Once, the youth minister at my church, Brother David, told me that he wasn?t racist. He said, ?There are black people and there are n-words.?

He actually said ?n-words.?

When my church friend Chris told his dad, a deacon, about a fine black girl he saw at the mall, his dad told him he would beat his ass if he ever ?brought a n***er home.?

Ultimately, to get the money footage, the showrunners eventually went to Gary?s, after asking someone in town where they could find the Klan. I don?t remember exactly what the two men said either, but they were Klansmen, so use your imagination.

A great place to live?

In the CNN story I mentioned earlier, the reporter notes that a billboard was placed along the highway to ?attract black families.? I remember seeing that same sign on the way home from college, back when my parents still lived there. It had a stock photo of four kids, including one black girl, and read ?Vidor: A Great Place to Live.?

I chortled a little bit. Hey, at least they?re trying.

If there?s one thing coastal media elites love more than talking down to or demonizing Southern ?white trash,? it?s a nice redemption story that reaffirms their ideas of the ceaseless forward march of progress. The author of that CNN piece wrote: ?In fairness, Vidor had changed, at least somewhat. It?s no longer a city that actively shuns blacks. In fact, African-Americans often shop there, even if very few are residents.?

A year prior, in 2005, the Associated Press published a piece about Vidor welcoming black victims of Hurricane Katrina. After reciting a litany of past horrors, the reporter told stories about white folks opening their hearts to black people in their time of need.

That same year, there was a hate crime in the town. The home of a mixed race couple was burned down and racial slurs were found on their detached garage.

I don?t mean to be cynical. Vidor is full of lovely people who are gentle, good, and Christian in the truest sense of the word. It also has more than its fair share of the other kind of people, and I can?t rightly say which represents the ?true Vidor.?

As late as 2003, the Klan was still holding events in Vidor?s public buildings. A post on the white supremacist forum Stormfront advertised a ?lecture and viewing of Ku Klux Klan memorabilia ? No NON whites allowed! No jews or jewsmedia allowed! [sic]? to be held in the Vidor Community Center to commemorate the anniversary of their fight against integration.

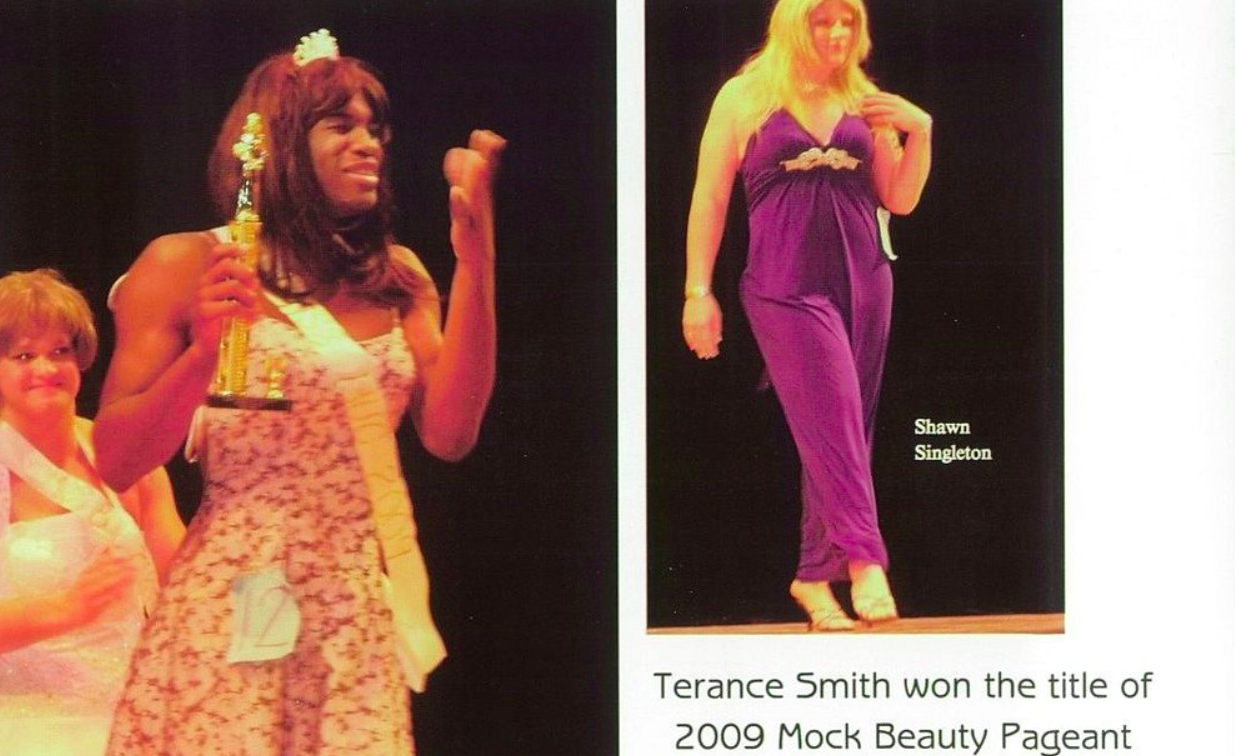

Vidor also apparently has at least one black family living there ? or it did in 2009.

While researching this story, I came across a yearbook picture of a black student taking part in a Vidor tradition more sacred than BBQ or even football: Dressing up like a woman for a cheap laugh.

(Stana St. Ana / Flickr / Creative Commons)

(Stana St. Ana / Flickr / Creative Commons)

It was a time of ?hope and change.? Obama was president and Terance Smith was crowned queen of the Vidor High School?s 2009 Mock Beauty Pageant.

But the presence of black people doesn?t mean the absence of racism in Vidor. James Byrd, Jr. was dragged to death behind a truck just a stone?s throw away in Jasper, a town that?s more than half black. And I have to wonder what life was really like for Terance Smith. I read some comments in forums from around that time that also claimed Vidor had truly changed, and that you would ?get beat up in VHS if you said the n-word.?

If that?s actually the case, it would really be something. At the very least, Smith was obviously popular enough in school to win the contest, and he stuck around long enough to be in the yearbook. That?s some kind of progress.

We never had a single black kid in our class when I was in school but we did come close one time. I never saw him, but word around the field house was that he was joining the football team and he?d be coming to practice.

I walked in on three of my teammates huddled around one of their lockers giggling.

They were making nooses out of shoelaces.