Structure is the most crucial element of writing for the screen. Countless screenwriting books have been written on the topic, more or less saying the same thing. If you want to read one, they?ll cover it better than I can in this single short article. And honestly, I?m probably going to tell you some things that are wrong here. The screenwriting structure book I hear talked about the most these days is Save the Cat by Blake Snyder. Though I have not read it, so I can?t personally recommend it.

The way acts are laid out in a television script can be different than the three act dramatic structure that I?m referring to right now. I?ll get to television structure in terms of commercial breaks at the end of this article. For right now I?m going to be taking us through dramatic structure.

Three Act Structure

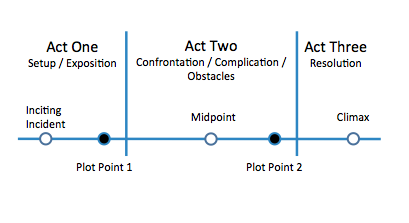

Three act structure: the thing, along with what a protagonist is, that you probably remember from middle school English class. Pretty much all dramatic fiction follows this form. Each of the acts roughly covers a third of your story and are traditionally referred to as something like set-up, confrontation, and resolution. Here?s a graphic I found that somebody made that is more or less accurate (I would never recommend being too dogmatic about this stuff):

In the first act, you set-up your characters, themes, setting, and central conflict. In the second act, your protagonist attempts to solve the central conflict but obstacles (and your antagonist) get in their way. And in the third act, through a personal growth, the protagonist is able to resolve the central conflict of the story, which may include thwarting the antagonist if there is one.

To give a concrete ? and popular ? example: act one, your character climbs up a tree; act two, you throw rocks at them; act three, your character climbs down from the tree (and maybe they?ve got an apple now).

Typically, your acts will not be equal lengths. Second acts are usually the longest (not always) and third acts are usually the shortest (almost always). A lot of screenwriting manuals demand that you get to your act breaks by a specific page, but I?m of the opinion that it depends on the story you?re telling.

In the last original pilot I wrote, my first act (including cold open) was about twelve pages, my second act was ten pages, and my third act was eight pages (including the tag). I think it?s pretty typical to have a long first act in a pilot with everything you need to set up. But maybe I just did it wrong? You probably shouldn?t be listening to me.

Act One

Like I said, the first act is for you to set up the situation. Your world, your characters, your central conflict ? everything your audience needs to know to understand what they?re watching. Think of the opening sequence of Star Wars, even without the opening crawl. You?ve got battling spaceships, lasers, rebels, imperials, a big scary guy head-to-toe in black. From the first frame, you get what Star Wars is about because it uses visuals to establish the world. It?s clear and effective.

The central conflict of the movie ? the Rebels stealing the Death Star plans and their quest to destroy it is also established within the first few minutes. The Empire boarding the Rebel spaceship to retrieve the plans is what we call the inciting incident of the story. Everything that happens in the story is because of this event. Our protagonist (Luke Skywalker) becomes involved in the events of galactic civil war because a space battle happened above his home planet and two droids managed to wind up on his farm carrying the plans for an Imperial battle station.

His journey from farm boy to Jedi Knight is his character story. He wants nothing more than to get away from his uncle?s farm and off Tatooine. Without his character story set up in the first act, he would not be able to save the day in the third act. Don?t neglect this. Setting up your protagonist and their central need is the most important piece of business in your first act.

Setting up your protagonist and their central need is the most important piece of business in your first act.

At the end of the first act, there will be a turning point often referred to as the call to action. In TV, it?s often referred to as a complication. Partly because the stakes are way lower in a random episode of Friends than they are in Star Wars. The story beat at the end of the first act is the point of the story where your protagonist makes an affirmative decision to pursue their goals and see the story through.

In Star Wars, this moment happens when Luke comes back home to find that his aunt and uncle have been murdered by the Empire (calling this moment a complication is a bit of an understatement). So he makes a decision to go with Obi-Wan Kenobi, learn to be a Jedi Knight, and help the Rebel Alliance. Without that affirmative choice from the protagonist to pursue his goals at the end of the first act, the rest of the movie does not happen and the Empire wins.

While these beats might not be so stark in your pilot script, they?re still there. Let?s go back to Haunted Bakery. Let?s say the pilot begins with a cold open (pre-credits scene). We can use this opportunity to introduce the audience to everything it needs to know about the show ? who the main character is, where it takes place, what is the tone of the show, and whether or not we are in a world inhabited by ghosts.

If I were to write this pilot (I?m not going to), I would set this scene in the bakery. Our protagonist is getting everything prepared for the grand opening, making sure everything is just so, and then there?s a ghost sneaking around that scares the shit out of her for a funny punch at the end.

Not much to it, sure, but this opening scene tells the audience everything it needs to know. Our main character is about to open a bakery. She cares about the bakery. The show is probably gonna take place in this bakery. The show is a comedy. The bakery is haunted. In probably what would be a two minute scene, you?ve given the audience enough information to know what they?re watching and to decide whether or not they want to continue.

Obviously, your cold open (or opening scene if you choose not to include a cold open) does not need to be this on-the-nose. But even comedies that are not extremely broad like Haunted Bakery would operate similar to this. The opening scene in Aziz Ansari?s Master of None, a prestige half-hour comedy if ever there was one, opens on the protagonist having sex when the condom breaks. He and the woman google whether or not you can get pregnant from precum and then order an Uber to get a Plan B pill. There are no ghosts and no bakeries, but you pretty much get the gist of what the show will be from this first scene: navigating dating and relationships in the modern era.

Cheers also has an effective cold open. Sam preps the bar for opening that day. He lovingly puts his hand along the molding as he walks by. A kid walks in and orders a beer and after a comedic bit between the two of them, Sam rejects his fake ID. So we know that Sam owns a bar. He loves the bar. He cares about his customers. He?s the kind of guy who does the right thing. The show is a comedy. We pretty much know what Cheers is from now on. Even though the character story of this episode is Diane?s, we learn that Sam is the heart of the show.

The rest of your first act will further introduce the audience to your world, your characters, the show?s (episode-wise and series-wise) central conflict, your protagonist?s goal, your antagonist and their goal (if you have an antagonist), and all the other necessary information the audience needs to know to enjoy your show.

Haunted Bakery?s first act feels like it would play out with beats of the protagonist dealing with the fallout of her first encounter with a ghost. She thinks she?s going crazy, she tells her friends, asks her landlord, tries to ignore the ghost and soldier ahead ? however comedically we can relay information about the world, character, and situation to the audience. I would end the first act of this show with her call to action. The ghosts tell her to get out of there forever, but she refuses. If she runs, her dream of opening this bakery is all over. She?s staying, but the ghosts are going to do everything they can to run her out.

So we have a protagonist and an antagonist with equal yet opposing goals. Neither can achieve their own goals without thwarting the other?s. The conflict of the whole series is also the conflict of the pilot episode. And we?ve set this all up in the first ten-or-so pages.

Act Two, Part One

Okay, ?three acts? is kind of a misnomer because your second act is split in two. I?ll get into why at the end of this section. But it fits that this act is typically referred to as the confrontation considering our Haunted Bakery pilot just set up a confrontation between the protagonist and antagonist. Great writing on a very silly show premise, right gang?

?guys?

Act Two will play out as exactly that ? a series of escalating comedic confrontations between the protagonist and whatever is standing in the way of achieving their goals. Sometimes it?ll be ghosts. Sometimes it will be your protagonist?s boss. Sometimes it?ll be a toilet that refuses to be fixed. Sometimes it will be your own protagonist?s refusal to admit that he?s wrong and he keeps screwing this up for himself because of that. Whatever it is, your protagonist needs to want to achieve something by the end of the episode and the whole of the second act is based around preventing your character from achieving it.

Your protagonist needs to want to achieve something by the end of the episode and the whole of the second act is based around preventing your character from achieving it.

For the first half of the second act, Haunted Bakery feels like it should progress through a series of escalating incidents between the baker and the ghosts. She tries to drive them out to no avail. They mess with her baking stuff and generally make life hell for her. As with all comedy and drama, this should escalate, each beat bigger than the last.

Midpoint

The second act is split in two parts mostly because of the importance of the story?s midpoint. It?s called that because it?ll happen pretty much exactly halfway through your script. It?s another complication, like the end of the first act. But it also acts as the point of no return for your protagonist. The stakes get higher and now our hero must see the journey through. Shit gets real at the midpoint.

In Star Wars, the midpoint is when they get sucked into the Death Star and are deep in enemy territory. In Jurassic Park, it?s when the power gets shut off and all the dinosaurs are loose. In the Cheers pilot, the complication is a bit softer but coincides with the episode?s commercial break. Diane?s fianc Sumner has still not returned from his ex-wife?s house and she?s stuck with these strange people in this strange bar. It?s not a huge beat, but it marks the moment where Diane starts being doubtful about her fianc and their engagement. Something changed inside Diane even if dinosaurs aren?t loose in the bar.

Haunted Bakery?s midpoint seems to me like it would involve the ghosts going one step further than they had before. Instead of just messing with our protagonist personally, they ruin an entire order for a potential client right as it?s due, jeopardizing the bakery?s opening. Now it?s not a matter of them playing tricks or scaring her ? now the ghosts are directly interfering with her livelihood. Things are different because of the midpoint and now the second half of the script has a new urgency.

Act Two, Part Two

The second half of Act Two functions a lot like the first half, with escalating beats of your hero trying to accomplish something and whatever is standing in their way messing with them. But because of the midpoint complication, things have become more urgent and the stakes have gotten higher. Luke Skywalker needs to rescue the Princess and get out of the Death Star right under the Empire?s nose. But if you?re writing a light comedy about a group of friends who hang out together, ?more urgent? and ?higher stakes? are relative to the reality of your show. You can have higher stakes and still have not much be at stake.

The second act ends with another complication, but is also the low point for your protagonist. In Cheers, Diane learns that Sumner has instead gone to Barbados with his ex-wife. Obi-Wan Kenobi dies in Star Wars, leaving Luke alone for the first time. At this point in the story, your character is at a point where they can quit or choose to proceed. If they quit, the story is over and presumably they go lay down and die somewhere. If they choose to proceed, the third act begins.

At this point in the story, your character is at a point where they can quit or choose to proceed.

This moment also sets up your third act. Haunted Bakery?s second act would end with her store a mess, the ghosts running amok, and it?s just two hours until the grand opening. Since this is the lowest point for the protagonist, the antagonist is at their highest point. So the ghosts believe that they?ve won and driven out the baker.

But she chooses to see it through, ensuring the story?s resolution and a third act full of wacky ghost antics.

Act Three

The resolution. This is where you tie up everything that you set up in your first act into a tidy bow. But since this is television, you leave room for more stories to take place after this. The baker must thwart the ghosts but not, you know, thwart them.

The action of your story will come to a point in the climax ? the most heightened piece of action in the story, but also when your protagonist uses what they?ve learned during the course of the story to win the day.

I love using Star Wars as an example because Luke is only able to destroy the Death Star by trusting his feelings and using the Force. If you put Luke Skywalker from the beginning of the story in this spot, he would have crashed his X-Wing into the side of the Death Star. He couldn?t have done it. Only through the growth of character that took place because of the events he lived through during the course of the film was he able to defeat the bad guys. And then the climax of the movie is a literal explosion.

That?s what makes it a story: the events of our lives and how they change us.

Again, we?re writing comedy here so this moment is not going to be so stark. It could be as small (and possibly should be) as your character making a gesture towards another character that they otherwise would not have at the beginning of the story. They can give up their seat on the bus if that?s what resolves the story, both of the episode and for the character. What?s important is that it involves a personal growth for that character. The protagonist can even not achieve their goal as long as they fail to do so in a way that is satisfying to the audience and that the character is altered by the experience in some way. Which is basically how every episode of Wonder Years ended. Even if they don?t necessarily learn anything, they were affected by the experience of the previous twenty-two minutes of screentime. That?s what makes it a story: the events of our lives and how they change us.

On this philosophical note, let?s wrap up Haunted Bakery. The third act proceeds, taking place during the bakery?s grand opening. She?s servicing customers while thwarting ghosts, basically doing a highwire act to make it look like everything?s going smoothly to her customers while quietly losing her mind trying to make these ghosts go away. It?d be very I Love Lucy. It?s hard to say what the climax would be without a firm hold on who this character is, what her flaws are, and what motivates her. But, for example, it could be something like just instead of trying to hide the ghost, she actually calls his bluff and lets him attack someone. He doesn?t do it so as not to reveal himself to a large group of people. The protagonist learns something about herself as a result (stop trying to make everything so perfect?) and a new equilibrium is established between her and the ghosts for the series going forward.

Diane agrees to work at Cheers because she finally drops her patrician veneers, admits to herself and Sam that she needs a job and waiting tables at this bar full of weirdos is something she?d enjoy doing. Something she never would have done if the specific events of that episode had not transpired.

After the climax, especially on a time-sensitive medium like television, you want to wrap up your story as quickly as possible. Star Wars does it in like two minutes, if that. In TV, you?re gonna want to do it even quicker than that. A post-commercial tag scene is a fun way to tie up loose ends. Speaking of?

Television Structure

Talking about acts and act breaks in television is a little bit different. Not because the three act structure doesn?t apply, but because ?acts? in the script are defined by how many commercial breaks there are and where they fall. Which depends mostly on the network that the show is on. Until the last decade or so, most half-hour television shows would have a commercial break halfway through the episode. So shows would get split into two acts. The end of the first act wouldn?t end with the end of the dramatic first act, but rather with the midpoint (the Cheers pilot follows this structure). When I worked on a show on Nickelodeon, we also followed this act structure. But I think that?s because by law there are fewer commercials on kid?s television.

I wrote on a show for Netflix, which has no commercial breaks. So we split the scripts into three acts anyway for our own (and production) purposes. I?ll get into how to break that down in the script stage part of this series.

Personally, when I?m writing a sample pilot, I split it up into three acts and split those act breaks along the traditional dramatic three act structure. I also use a cold open in the beginning and a short one page tag at the end. I?d recommend splitting your pilot into three acts just because that?s what most shows do now and it?s the easiest way to do it. Whether you use a cold open or a tag is up to you, but most shows do use cold opens nowadays. Also, I think Fox shows have four acts. So if you?re writing a spec script for another show, see how many commercial breaks it has, where they fall, and adjust accordingly.

A, B, and C Stories

I may get into this a bit in the next section, but when you?re writing a television show, a lot of time they have an A and a B story. Sometimes a much lighter C runner as well. You might not need a B story in the pilot even if a typical episode of your show would have one. Cheers does not have a B story in the pilot even though most episodes of the show do.

The A story is the main plot of your episode. For the most part, your protagonist will get this story. They definitely will in the pilot. The B story is a concurrent subplot featuring supporting character or characters as a way to service them and also give you something to cut away to between your main story beats. You might also have a small C story (or a runner) to service another character. In a typical episode of The Office, Michael Scott would get the A story, Jim and Pam would get the B, and Dwight would get the C.

Also, think about how great Seinfeld was at weaving two, three, or sometimes even four stories together and dovetailing them together in the climax. But again, it?s not something you?ll have to worry about in your pilot. Like I said in the section about character, the character that really needs to be serviced is your protagonist. If you are writing an ensemble show, you will probably need a B story, but with an A story getting priority.

You would typically structure your story cutting back and forth between A story scenes and B story scenes. You?ll want to end your acts with your A story because the A story features your lead and will generally have more beats, as well as higher importance and stakes.

Next time in Part 4: Pre-writing and Outlining

Part 1: Concept & ConsiderationsPart 2: CharacterPart 3: StructurePart 4: Pre-writing & OutliningPart 5: Writing the ScriptPart 6: Re-writing, Editing & What to Do Next