A Baroque masterpiece about decadence and decay

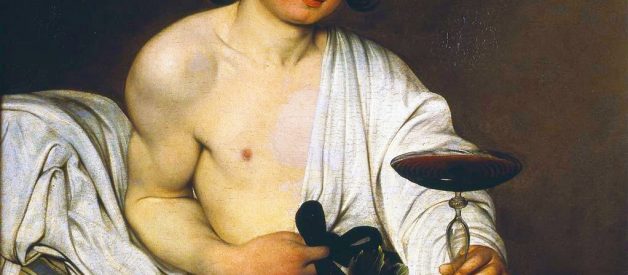

Detail of ?Bacchus? (c.1596) by Caravaggio. Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Source Wiki Art (public domain)

Detail of ?Bacchus? (c.1596) by Caravaggio. Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Source Wiki Art (public domain)

Caravaggio?s painting of Bacchus contains all the revelry associated with the mythological libertine bubbling beneath its surface. It is this sense of storm-beneath-the-calm that makes it such a potent work of art.

Bacchus, the god of wine, is usually shown drunk; Caravaggio?s Bacchus is serene and self-contained. He is often seen riding a triumphal carriage drawn by tigers, leopards or goats; in Caravaggio?s version the Bacchic procession is either yet to begin or else all over with. Or perhaps this Bacchus has altogether different plans?

Caravaggio, who was born in 1571, painted this work at the age of around 24. It was commissioned by Cardinal Del Monte, an Italian diplomat who became one of Caravaggio?s early patrons.

?Bacchus? (c.1596) by Caravaggio. Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Source Wiki Art (public domain)

?Bacchus? (c.1596) by Caravaggio. Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Source Wiki Art (public domain)

The painting shows Bacchus as a callow youth. The boy-god is swathed in autumnal vine leaves, draping over a thicket of black hair that itself might be a bunch of black grapes. His cheeks are plump and red. He is half-robed, clutching the black ribbon of his robe in one hand and a glass of wine in the other. He is reclined before a table or stone slab bearing a carafe of wine and a basket of overripe fruit with pomegranate, pear, apple, peach, quince, fig, plum and grape.

Bacchus, or Dionysus as he is known in Greek, was originally a fertility god worshiped in the form of a bull or a goat. The cult of Bacchus inspired frenzied rituals, where devotees would eat raw flesh and dance to the drumming of tambourines.

A more typical representation of Bacchus leading his triumphal procession. ?Bacchus and Ariadne? (1520?1523) by Titian. National Gallery, London, UK. Source Wiki Art (public domain)

A more typical representation of Bacchus leading his triumphal procession. ?Bacchus and Ariadne? (1520?1523) by Titian. National Gallery, London, UK. Source Wiki Art (public domain)

Painted depictions tended to show Bacchus as a naked youth wearing a crown of vine leaves and leading his triumphal parade of hedonistic revellers, as in the well-known version by Titian, painted around 1523. By the time of the Italian Renaissance, the lively and passionate spirit of Bacchus had gained meaning as a complimentary opposite to Reason, as personified by Apollo.

Detail of ?Bacchus? (c.1596) by Caravaggio. Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Source Wiki Art (public domain)

Detail of ?Bacchus? (c.1596) by Caravaggio. Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Source Wiki Art (public domain)

In Caravaggio?s work, the setting is opulent yet also far more sedate than the Titian painting.

For me the force of Caravaggio?s painting lies in two details: The first is the particular shape of the wine glass offered by the boy, a glass so extraordinarily shallow that it seems to emanate decadence itself. The wine inside shimmers with fresh ripples ? as if the boy is shaking a little with excitement as he passes it. All of the energy of the painting is concentrated in this wine glass. There is no further Bacchanalian revelry, no tambourine-thumping Maenad. The boy seems not the least bit drunk, only placid and self-assured as he welcomes us into his private soire. As if to underline the worldly setting, the second detail that always catches my attention is the grubby pillow on the bottom-left of the painting, exposed beneath the sheets, the one with the blue stripe, reminding us that the opulence here is makeshift and temporary.

Detail of ?Bacchus? (c.1596) by Caravaggio. Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Source Wiki Art (public domain)

Detail of ?Bacchus? (c.1596) by Caravaggio. Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Source Wiki Art (public domain)

Along with this sense of the makeshift, there is also something transitory in the feel of the piece. The fruit in the basket is beginning to rot and the vine leaves on the boy?s head are turning brown. These elements hint at a vanitas undertone, a symbolic theme in art that attempts to show the transience of life and the futility of pleasure. With this ephemerality and suggestion of impending demise, Caravaggio gives the painting an additional tragic element.

This painting has always felt to me like an invitation to something velvet, a certain lurid promise beneath a veneer of calm. The sensuality of scene is a prominent aspect, and many critics have written about the homoerotic echoes of the work. Art historian Donald Posner, for instance, felt that the latent homoeroticism in the painting was actually alluding to Cardinal Del Monte?s sexuality and his relationships with the young boys who frequented his inner circle.

?Bacchus? (c.1596) by Caravaggio. Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Source Wiki Art (public domain)

?Bacchus? (c.1596) by Caravaggio. Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Source Wiki Art (public domain)

For Caravaggio, the subtle gradations between light and dark that the Bacchus painting illustrates would be a theme he continued to probe through the rest of his career. By no means untouched by trouble in his personal life, Caravaggio would go on to use light and dark in more figurative ways, yet without losing the psychological ambiguity he so successfully located in this early Bacchus depiction.

Christopher P Jones writes about art and other things at his website.