A complex description of religious piety and artistic self-assertion

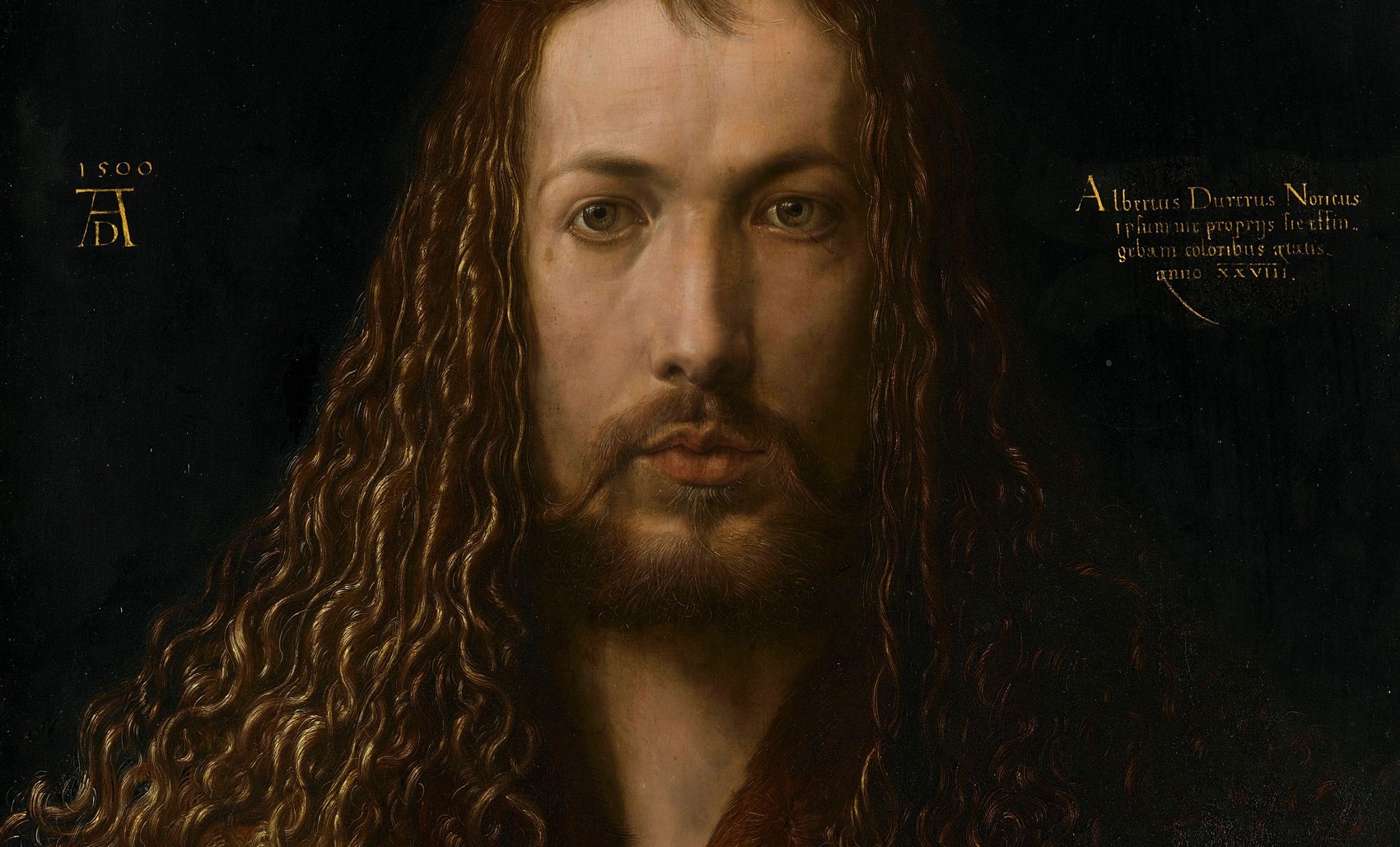

Self-portrait (1500) by Albrecht Drer. Oil on lime wood. Alte Pinakothek museum, Munich. Source Wikimedia Commons

Self-portrait (1500) by Albrecht Drer. Oil on lime wood. Alte Pinakothek museum, Munich. Source Wikimedia Commons

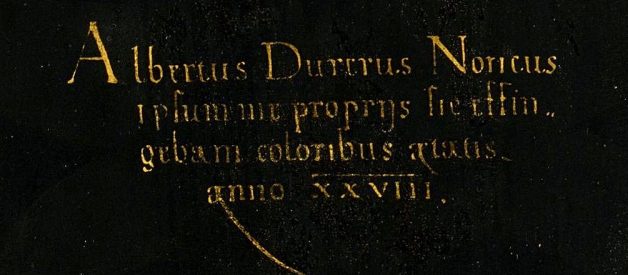

Albrecht Drer was 28 when he painted his self-portrait. The inscription in the top-right of the painting tells us so: ? I, Albrecht Drer of Nuremberg have portrayed myself in my own paints at the age of twenty-eight.?

Detail of ?Self-portrait? (1500) by Albrecht Drer. Oil on lime wood. Alte Pinakothek museum, Munich. Source Wikimedia Commons

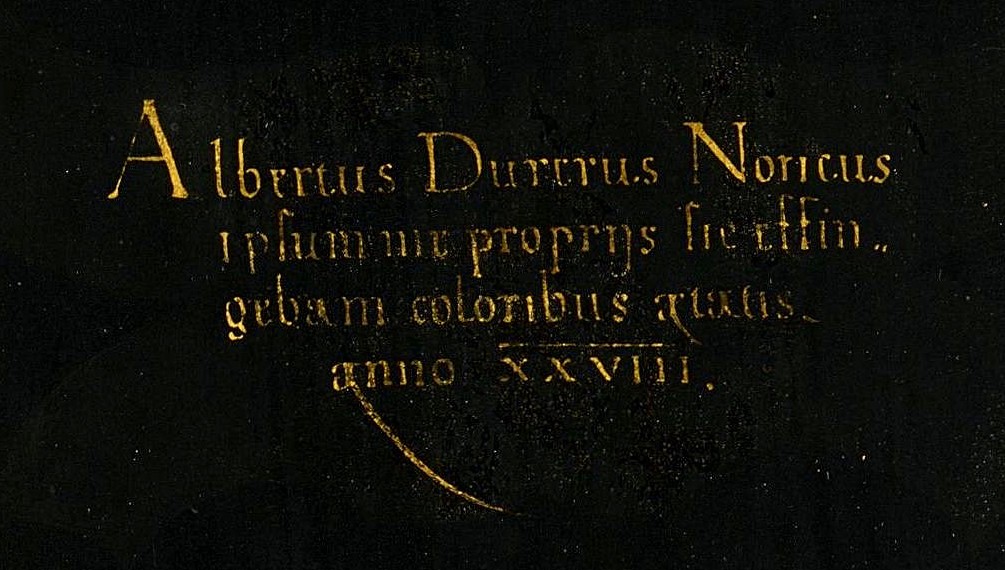

Detail of ?Self-portrait? (1500) by Albrecht Drer. Oil on lime wood. Alte Pinakothek museum, Munich. Source Wikimedia Commons

From our modern perspective, it may seem a young age to paint such an assured (and self-assured) depiction. The painted textures of the artist?s hair and coat are extraordinarily detailed, and the colour palette is mature in its restrained use of browns and creams.

Yet, by this point in his life, Drer had already been working as a craftsman and artist for over 15 years. From the age of 11 he worked in his father?s goldsmith?s workshop where he learned to draw and engrave. In 1486, age 15, he was apprenticed to Nuremberg?s leading painter Michael Wolgemut, whose workshop also designed stained glass and produced woodcut prints. It is likely that the young Drer was involved in the manufacture of the Nuremberg Chronicle, a huge illustrated world history whose 1,800 woodcut illustrations were prepared by the Wolgemut workshop.

Drer travelled widely during his youth, staying in Frankfurt, Cologne and Basel, and in 1494, an extended trip to Italy. Throughout this time he worked on numerous engraving projects, and by 1495 had set up his own workshop in Nuremberg. His reputation as a skilled illustrator and engraver was quickly establishing, so that by the time he made this self-portrait in 1500, he was famous across the continent.

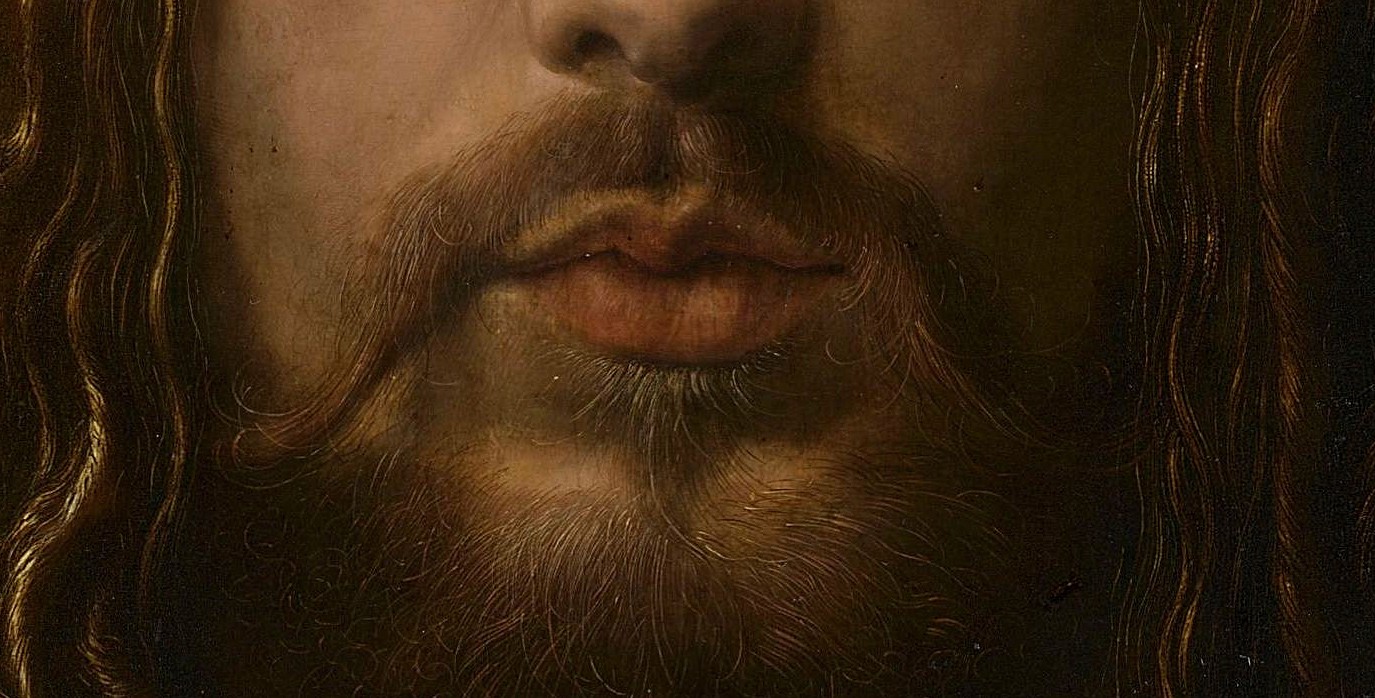

Detail of ?Self-portrait? (1500) by Albrecht Drer. Oil on lime wood. Alte Pinakothek museum, Munich. Source Wikimedia Commons

Detail of ?Self-portrait? (1500) by Albrecht Drer. Oil on lime wood. Alte Pinakothek museum, Munich. Source Wikimedia Commons

The first thing that tends to strikes viewers of the Self-portrait is its resemblance to Christ.

It is interesting to note that, in Drer?s time, it was believed that an eye-witness account Christ existed. It appeared in a letter written by a Roman official, Lentulus, supposedly a contemporary of Jesus, who gives a physical and personal description of Christ:

He is a man of medium size; he has a venerable aspect, and his beholders can both fear and love him. His hair is of the colour of the ripe hazel-nut, straight down to the ears, but below the ears wavy and curled, with a bluish and bright reflection, flowing over his shoulders. It is parted in two on the top of the head, after the pattern of the Nazarenes. His brow is smooth and very cheerful with a face without wrinkle or spot, embellished by a slightly reddish complexion. His nose and mouth are faultless. His beard is abundant, of the colour of his hair, not long, but divided at the chin. His aspect is simple and mature, his eyes are changeable and bright. He is terrible in his reprimands, sweet and amiable in his admonitions, cheerful without loss of gravity. He was never known to laugh, but often to weep. His stature is straight, his hands and arms beautiful to behold. His conversation is grave, infrequent, and modest. He is the most beautiful among the children of men.

Detail of ?Self-portrait? (1500) by Albrecht Drer. Oil on lime wood. Alte Pinakothek museum, Munich. Source Wikimedia Commons

Detail of ?Self-portrait? (1500) by Albrecht Drer. Oil on lime wood. Alte Pinakothek museum, Munich. Source Wikimedia Commons

Comparing Drer?s self-portrait with the letter from Lentulus, from the hair the colour of ripe hazel-nut to eyes changeable and bright, it is hard not to see a connection between the description and the painting.

Moreover, it is likely that Drer was acquainted with the description since the Lentulus letter was first printed in Germany in 1474 as part of the a ?Life of Christ? by Ludolph the Carthusian. It was later printed in Nuremberg in 1491 as part of the ?Introduction to the works of St. Anselm? ? Drer was living in Nuremberg when he made his self-portrait of 1500.

It is now widely accepted that the letter from Lentulus was a forgery; still, the letter was published widely and for a long time was taken as a direct eyewitness account. It is not surprising, then, that artists of the period used the description as the basis for their own representations of Christ and that, subsequently, a certain look established itself in paintings of Christ, as can be seen in works by numerous artists, from Jan van Eyck and Leonardo da Vinci.

Images of Christ. Left: Vera Icon (1439) copy after Jan van Eyck, source Wikimedia Commons. Right: Salvator Mundi (circa 1500) by Leonardo da Vinci. Oil on walnut wood. Louvre Abu Dhabi. Source Wikimedia Commons

Images of Christ. Left: Vera Icon (1439) copy after Jan van Eyck, source Wikimedia Commons. Right: Salvator Mundi (circa 1500) by Leonardo da Vinci. Oil on walnut wood. Louvre Abu Dhabi. Source Wikimedia Commons

So, did Drer intentionally paint himself in the guise of Jesus Christ? And if so, for what purpose?

In Drer?s day, paintings were usually made to commission. In contrast, prints made from woodcut and metal engravings were typically made for speculative sale. With this in mind, it is likely that the self-portrait was painted as a virtuoso piece rather than for a specific client: it was an exercise that allowed Drer to show off his exceptional observational skills and his technical abilities at depicting textures and facial features.

Still, there can be no doubt that the self-portrait was designed to resemble Christ. The portrait shows Drer looking directly out of the canvas, a common convention in Late Northern medieval depictions of Jesus. In contrast, a frontal pose like this was unusual for a secular painting.

So, what is going on here? There is perhaps one further detail in the painting that is worth examining, to gain a fuller understanding of the work.

The coat he is wearing is lined with marten fur (martens are a cat-sized animal belonging to the mustelid family, native to Northern Europe). Marten fur was also a common material used in the manufacture of paintbrushes. The artists grips the fur between the fingertips of his right hand, and in doing so, creates an unusual shape with the arrangement of his thumb and fingers.

Detail of ?Self-portrait? (1500) by Albrecht Drer. Oil on lime wood. Alte Pinakothek museum, Munich. Source Wikimedia Commons

Detail of ?Self-portrait? (1500) by Albrecht Drer. Oil on lime wood. Alte Pinakothek museum, Munich. Source Wikimedia Commons

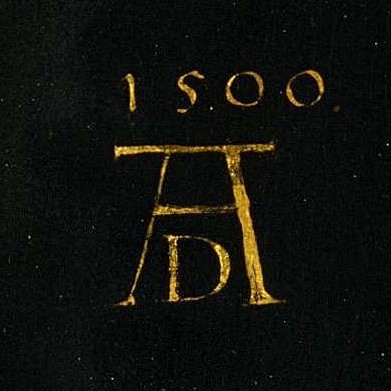

It?s possible to interpret the shape of his thumb and first finger as forming the shape of the letter A, and the shape of his first and middle finger the shape of the letter D. Combined, they make the artist?s initials A.D ? an echo of the monogram that Drer signed many of his works with, appearing top-left in this painting.

Drer?s monogram, from ?Self-portrait? (1500) by Albrecht Drer. Oil on lime wood. Alte Pinakothek museum, Munich. Source Wikimedia Commons

Drer?s monogram, from ?Self-portrait? (1500) by Albrecht Drer. Oil on lime wood. Alte Pinakothek museum, Munich. Source Wikimedia Commons

So his fingers are self-referential. And since they are fingering the marten fur ? as used in the paintbrushes ? so Drer is telling us that he owes his position in society to his skill with his paintbrush.

In this way, Drer?s representation of himself as Jesus Christ should not be read as blasphemous audacity. It is more likely that his self-depiction was accepted and understood by his contemporaries as part of the tradition of the ?Imitation of Christ? ? that is, the practice of following the example of Jesus as part of a pious Christian life.

With the self-referential hand gesture, Drer?s intention is to elevate the status of the artist to a higher plane. In other words, an expression that his artistic talents are God-given.

Self-portrait (1500) by Albrecht Drer. Oil on lime wood. Alte Pinakothek museum, Munich. Source Wikimedia Commons

Self-portrait (1500) by Albrecht Drer. Oil on lime wood. Alte Pinakothek museum, Munich. Source Wikimedia Commons

Would you like to get?

A free guide to the Essential Styles in Western Art History, plus updates and exclusive news about me and my writing? Download here.

Christopher P Jones is a writer and artist. He blogs about culture, art and life at his website.