When this photograph capturing the suffering of the Sudanese famine was published in the New York Times on March 26, 1993, the reader reaction was intense and not all positive. Some people said that Kevin Carter, the photojournalist who took this photo, was inhumane, that he should have dropped his camera to run to the little girl?s aid. The controversy only grew when, a few months later, he won the Pulitzer Prize for the photo. By the end of July, 1994, he was dead.

Emotional detachment allowed Carter and other photojournalists to witness countless tragedies and continue the job. The world?s intense reactions to the vulture photo appeared to be punishment for this necessary trait. Later, it became painfully clear that he hadn?t been detached at all. He had been deeply, fatally affected by the horrors he had witnessed.

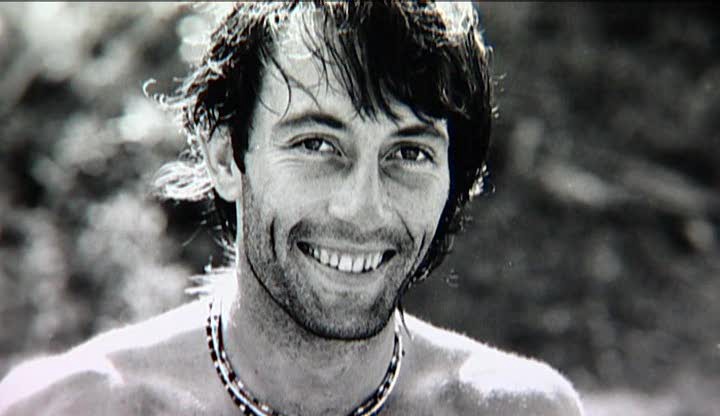

Carter grew up in South Africa during apartheid. He became a photojournalist because he felt he needed to document the sickening treatment not only of blacks by whites, but between black ethnic groups as well, like those between Xhosas and Zulus.

Joining ranks with only a few other photojournalists, Carter would step right into the action to get the best shot. A South African newspaper nicknamed the group the Bang-Bang Club. At that time, photographers used the term ?bang-bang? to refer to the act of going out to the South African townships to cover the extreme violence happening there.

In a few short years, he saw countless murders from beatings, stabbings, gunshots, and necklacing, a barbaric practice in which a tire filled with oil is placed around the victim?s neck and lit on fire.

Carter took a special assignment in Sudan, where he shot the famous vulture photo. He spent a few days touring villages full of starving people. All the while, he was surrounded by armed Sudanese soldiers who were there to keep him from interfering. The photos below are evidence that even if he decided to help the little girl, the soldiers wouldn?t have allowed it. The first was shot by Carter himself.

After receiving a number of phone calls and letters from readers who wanted to know what happened to the little girl, the New York Times took a rare step and published an editor?s note describing what they knew of the situation. ?The photographer reports that she recovered enough to resume her trek after the vulture was chased away. It is not known whether she reached the [feeding] center.?

Most of us have trouble comprehending how Carter and the rest of the Bang-Bang Club did this kind of work day after day. But it turns out that it took its toll on them, and in Carter?s case, fatally so. Carter?s daily ritual included cocaine and other drug use, which would help him cope with his occupation?s horrors. He often confided in his friend Judith Matloff, a war correspondent. She said he would ?talk about the guilt of the people he couldn?t save because he photographed them as they were being killed.? It was beginning to trigger a spiral into depression. Another friend, Reedwaan Vally, says, ?You could see it happening. You could see Kevin sink into a dark fugue.?

And then his best friend and fellow Bang-Bang Club member, Ken Oosterbroek, was shot and killed while on location. Carter felt it should have been him, but he wasn?t there with the group that day because he was being interviewed about winning the Pulitzer. That same month, Nelson Mandela became president of South Africa.

Carter had focused his life on exposing the evils of apartheid and now ? in a way ? it was over. He didn?t know what to do with his life. On top of that, he felt a need to live up to the Pulitzer he?d won. Soon after, in the fog of his depression, he made a terrible mistake. On assignment for Time magazine, he traveled to Mozambique. On the return flight, he left all his film?about 16 rolls he had shot there?on the plane. It was never recovered. For Carter, this was the last straw. Less than a week later, he was dead. He drove to a park, ran a hose from the exhaust pipe into his car, and died of carbon monoxide poisoning.

Yes, winning the Pulitzer Prize put pressure on him, but it didn?t lead directly to his death. Rather, it only added to the pile of stress and guilt he had accumulated while documenting some of the most gruesome corners of the world. But thanks to his brain-searingly memorable photo, the famine in Sudan became internationally known. Carter left an indelible mark on the planet?s consciousness.