and when is more protein better?

Protein ? the one macronutrient that can do no wrong!

Protein ? the one macronutrient that can do no wrong!

Are you getting enough protein? What does ?enough? mean for YOU?

From a medical perspective, it?s clear that most of us are getting plenty of protein. Protein deficiencies are rare in wealthier countries, thanks to our love affair with protein-rich foods. (Note: Protein malnutrition remains an important health issue in the developing world, where it often coincides with too few total calories and/or a narrow, unbalanced diet.)

Globally, we consume about one third more protein than the official recommended intake of 50 grams per day (based on 0.8 g/kg), with North Americans topping the charts at over 100 grams per day and Europeans coming in not far behind. If more protein is always better, then this is great news for North America and Europe. But, what if ?enough? protein truly is enough, and more isn?t necessarily better?

As a scientist (PhD in genetics), I have a deep respect for the importance of providing our bodies with enough of this critical building block of life. I also appreciate that human biology is both highly complex and individual, and that simple rules of thumb like ?more of a good thing must be better? rarely pan out.

To help you ? and me ? determine our optimal protein intakes, this article looks under the hood of the official guidelines and shares the potential pros and cons of boosting your intake beyond your basic needs.

Why Do We Need Protein?

Messy alphabet bead necklaces ? each bead is an amino acid

Messy alphabet bead necklaces ? each bead is an amino acid

Proteins are the workhorses and building blocks of life. We need a steady supply of them in order to repair old tissues, build new ones, and keep our cells humming. The bigger we are, the faster we are growing, the more tissue we have to repair and rebuild, the more protein we need.

When we look closely at proteins, we see chains of amino acids, averaging several hundred in length. All proteins are made from the same twenty amino acids, linked together in unique combinations. When you eat foods containing protein, your body breaks down the chains, and then reassembles the amino acids into whichever proteins it needs.

Individual amino acids also play signaling roles in the body, reporting on your nutritional status, which in turn influences the metabolic state of your cells.

What Are The Current Guidelines?

Current US guidelines for daily protein intake vary with age, as shown below. These numbers are Recommended Daily Intakes (RDIs), which means they tell you how much daily protein should meet the needs of most (97?98%) people.

- Under 1 year: 1.5 g/kg (highest in first few months)

- 1?3 years: 1.1 g/kg

- 4?13 years: 0.95 g/kg

- 14?18 years: 0.85 g/kg

- Adults: 0.8 g/kg*

Using myself as an example, these guidelines suggest that I can safely meet my needs with 48 grams of protein per day (60 kg x 0.8 g/kg = 48 grams). For those of you who think in pounds, take your weight and multiply by 0.36 g/lb (e.g. 132 lbs x 0.36 g/lb = 48 grams).

*Some studies suggests that older adults have higher basic protein needs. See discussion below under ?Is More Protein Better??.

Why 0.8 Grams Per Kilogram?

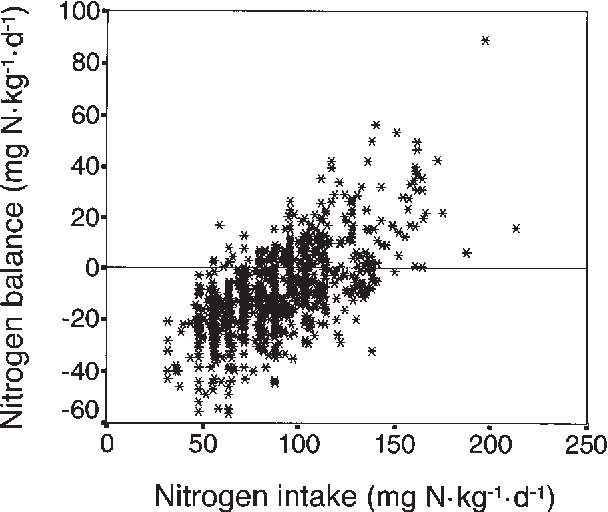

The widely used recommendation of 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram for adults stems from a 2003 meta-analysis including 235 healthy adults, happily going about their daily lives. To be clear, they were neither comatose (as some people think) nor serious athletes. Their diets were variable, roughly half were mixed, while the rest were split between plant-centric and meat-centric.

The authors first calculated the average needs across all subjects in all studies (roughly 0.65 grams per kilogram), then added a large cushion, known as two standard deviations. The RDI of 0.8 g of protein per kilogram of body weight is the number you get after this cushion is added.

It?s worth noting that this study used a method called nitrogen balance. This well-established method takes advantage of the fact that proteins are your only dietary source of the element nitrogen. By testing subjects at several levels of dietary protein, researchers identify an intake amount where the amount of nitrogen that subjects consume matches the amount they lose naturally (through urine, skin, hair, etc). This level is known as zero nitrogen balance, and is the basis of all national and international protein recommendations.

This study formed the basis of the protein requirements of the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies, which informs dietary guidelines in both Canada and the US.

Even if you?re convinced (as I am) that the official requirements can keep most of us healthy, there is still a question left hanging:

When More Protein Is Better

Photo by Victor Freitas on Unsplash

Photo by Victor Freitas on Unsplash

While the RDA is ?enough? for an average, lightly active, healthy person to grow, develop, and thrive, there are times when more protein is better.

- Acute or chronic illness. Certain illnesses have well documented increases in protein needs, as reported in this 2013 review.

- Older adulthood. A 2014 European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism workshop on protein requirements in the elderly concluded that older adults should aim for 1.0?1.2 g/kg. Note: This figure is not universally accepted. It remains to be seen whether it will be adopted into official North American or European guidelines, in the same way that children and teens are advised to consume more than 0.8 g/kg.

- Maximizing muscle growth from strength training. Bodybuilders routinely consume double or triple the RDI in protein, in the hopes of maximizing their rate of muscle growth. Yet, a 2018 review and meta-analysis reported that benefits taper off after about 1.6 g/kg per day (double the RDI).

- Preserving lean muscle during weight loss. Higher protein diets can help preserve lean muscle mass while losing weight, though effect sizes are small to modest (to the tune of 400?800 grams difference) and findings across studies are inconsistent. Note: Protein is NOT a magic bullet for weight loss. The impact of protein on weight loss is secondary to bigger drivers like calorie deficit.

Keep the fat, spare the lean? This sister article dives deeply into the science of your protein intake impacts the loss of fat and lean muscle during weight loss.

As you determine your protein target, I urge you to be realistic about how much benefit to expect for a given protein ?boost?.

Do Those Following Plant-Based Diets Need More Protein?

Photo by Rustic Vegan on Unsplash

Photo by Rustic Vegan on Unsplash

Many plant-based proteins are less bioavailable than animal-derived proteins, that is to say, they are not 100% available for your body to use them. As such, it takes a bit more plant-protein to ensure the same amount of protein is absorbed.

The absorption ?hit? you take from plant-protein varies greatly, with proteins like soy matching animal proteins (no hit) and certain grains, like corn, falling much lower. The real-world impact of bioavailability is minimal in the developed world, where we tend to consume more than enough calories, including abundant amounts of protein from a variety of sources, as reported in these two plant-based studies: EPIC-Oxford and Adventist Health Studies.

For more discussion of protein needs by plant versus animal sources, check out this brief post (Fueled by Science).

How Sure Are We About The RDAs?

I disagree with those who scoff at the 0.8 grams per kilogram target, declaring it either an underestimate, irrelevant to their lives. I view it as a very solid protein target for average, healthy adults, such as myself. Here?s why:

Relevance

The adults in the underlying studies of protein needs were normal, healthy people, spanning a range of geographies, diets, and ages. Most of us, like it or not, are ?average?!

Consistency

Health authorities around the world have reached very similar conclusions. The World Health Organization recommends 0.75 g/kg for adults, while the European Food Safety Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition, and Allergies recommends 0.83 g/kg. This figure is also supported by more recent reviews of the data, such as in this 2014 meta-analysis.

Living proof

Unfortunately, there aren?t many studies of people in the developed world who consume exactly 0.8 g/kg per day. Even among communities where average protein intakes are lower, such as the plant-forward US Adventists, it?s only the lowest five percent that land very close to the RDI.

We have more data on people who consume protein levels just north of this target. They tend to be just as healthy, if not more so, than their higher protein counterparts, as supported by the US Adventists and the Epic-Oxford cohort. These studies don?t prove that eating less protein CAUSED better health (there are too many other factors going on here), but they do tell us that eating a tad more than ?just enough? protein is not harmful, when it comes the majority of outcomes examined: cancer, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and all-cause mortality.

Limitations

One noteworthy limitation of the current protein guidelines is the fact that they rely largely on data from studies using the nitrogen balance method. Some scientists advocate for a different method called IAAO (Indicator Amino Acid Oxidation), which overcomes some of the shortcomings of the nitrogen balance method. The handful of small studies done with this method have reported considerably higher targets than those obtained through nitrogen balance. For example, this small study of protein needs using IAAO (which tested 8 healthy adults) landed at an RDI of 1.2 g/kg. While these data warrant consideration, this method has its own limitations, and should not be seen as the ?real? answer ? particularly not with such small sample sizes.

It?s also worth noting that the adults in the studies underlying the guidelines were healthy, and not obese. Protein needs in obesity are unresolved. Indeed, many studies of overweight populations use grams of protein per kilogram of IDEAL weight, rather than actual weight. In other words, if someone weighs 60 kilograms, and gains 10 kilograms of fat, their protein don?t meaningfully change.

The Bottom Line

Despite how much we stress about getting ?enough? protein, most of us are getting plenty ? and then some. Adults in the developed world far exceed not only the well-supported official target of 0.8 g/kg but also the more generous targets suggested by advocates of a different experimental method. This is true both of omnivores and plant-based followers (vegans) alike.

While there are times when more protein is better, it?s important to weigh any upsides of more protein against potential downsides. The health impacts of a higher protein diet are controversial, and warrant their own discussion. My main reason for caution is that leading longevity researchers, such as Valter Longo and peers, steer us away from long-term high protein diets in order to avoid chronically stimulating growth signaling pathways.

A final, but worthwhile consideration in the ?optimal? protein conversation is how your protein target shapes your food choices. I value the dietary freedom that comes from not having to shape most of my food around any given nutrient.

Personally, I tend to naturally land at 1.0 g/kg protein thanks to my love of legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds ? a level that I view as not only safe, but generous.

Learn More

- Protein Primer 1: Meet Your Proteins and Amino Acids

- Protein Primer 2: From Bite To Bicep

- How To Get Enough Protein ? Animal Proteins Optional!

- How Much Protein Does My Child Need?

- Busting the Myth of Incomplete Plant Proteins

About Me

I am formally trained in human genetics (PhD) and spent the first decade of my career working in cancer research, drug development, and personalized medicine.

My new career chapter is dedicated to empowering others to make informed food choices, rooted in facts not fears. I?m particularly passionate about helping people to fall in love with the plants on their plates.

See more of my work and get healthy plant-based recipes: https://FueledbyScience.com

Originally published at https://fueledbyscience.com on December 12, 2019. Revised with more references and detail on January 15, 2020.