Written by Andrew Eliot Binder, a GoPeer tutor. Learn more here.

Written by Andrew Eliot Binder, a GoPeer tutor. Learn more here.

A Critical Essay on Frankenstein by Mary Shelley: A Balance of Spheres

Mary Shelley explores the contrast between isolation and society throughout her novel, Frankenstein. This stark dichotomy revolves around the concept of friendship and how characters treat their friends. By juxtaposing Captain Robert Walton and Victor Frankenstein, Shelley critiques isolationism and promotes companionship as vital to humanity?s prosperity. Her message condemns gender roles within Romantic society and ultimately provides a paradigm for the malign consequences of isolation.

Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein. Shelley was one of few celebrated woman authors in the Romantic Era.

Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein. Shelley was one of few celebrated woman authors in the Romantic Era.

The characters of Walton and Frankenstein are almost entirely alike. Unbeknownst to each other, both men share a strikingly similar childhood. In letters to his sister, Mrs. Saville, Walton recounts, ?I am self-educated: for the first fourteen years of my life I ran wild on a common and read nothing but our Uncle Thomas? books of voyages? I was passionately fond of reading. These volumes were my study day and night? (19, 16). Later in the novel, Frankenstein recalls, ?I was, to a great degree, self-taught with regard to my favourite studies? I read and studied the wild fancies of? writers with delight? (41). Almost identical, these self educations gave rise to similar curiosities. While Frankenstein ?desire[s] to divine?the secrets of heaven and earth,? Walton desires to ?ascertain the secret of the magnet? (38, 16). These ambitions to scientifically probe nature are driven by a common thirst for glory. Walton affirms to Mrs. Saville, ?I prefer glory to every enticement that wealth place[s] in my path? (17). Unaware of this statement, Frankenstein later describes his youthful mentality: ?Wealth was an inferior object, but what glory would attend the discovery if I could banish disease?? (42). Rather than a monetary reward, zealous curiosity and desire for glory motivate both men to set out on an enterprise; Frankenstein attempts to animate a man while Walton attempts to discover passage routes through the Arctic. It becomes clear, Shelley?s deliberate parallels between both male protagonists characterize them as practically the same man.

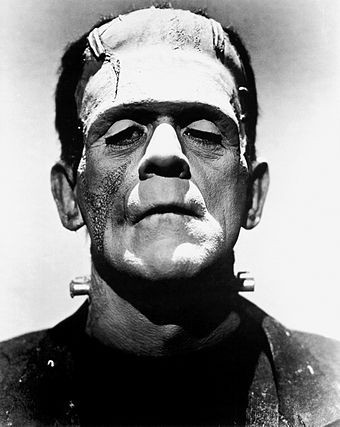

Victor Frankenstein

Victor Frankenstein

Shelley differentiates Walton and Frankenstein by only one character trait: their treatment of friends. Throughout the novel, Victor Frankenstein increasingly rejects his friendships and isolates himself. The first stage in this process occurs after months of intellectual stimulation at college in Ingolstadt. He recalls ? the unremitting ardour ? which made me neglect the scenes around me caused me to forget those friends who were so many miles absent, and whom I had not seen for so long a time? (55 , 56). Frankenstein altogether loses contact with his domestic relationships as he becomes more engrossed in working on his creation: ?I wished, as it were, to procrastinate all that related to my feelings of affection? I shunned my fellow-creatures? (56, 57). Upon William?s death, he reaffirms this emotional and geographical detachment: ?At first I wished to hurry on, for I longed to console and sympathise with my loved and sorrowing friends; but when I drew near my native town, I slackened my progress? (76). After his incredible inability to seek or provide consolation during William?s funeral and Justine?s death, Frankenstein severely deteriorates all social connections. In their first dialogue, Victor yells at his creature, ?Begone! I will not hear you. There can be no community between you and me; we are enemies? (103). Shortly thereafter, he ventures to Scotland with Henry Clerval and delays Elizabeth?s desire for marriage and his father?s desire for his homecoming. Frankenstein?s message to Clerval, ?do not interfere with my motions, I entreat you: leave me to peace and solitude,? and his retreat to the remote Orkney Islands represents the final act in his self-extrication from society. This act of isolation precipitates the creation?s murder of Clerval, Frankenstein?s closest friend, and drives him to lament, ?on the whole earth there is no comfort which I am capable of receiving? (183). At this point, Frankenstein irrevocably loses the ability to seek consolation in human society, as demonstrated by his secrecy toward Elizabeth before her murder on their wedding night. In rejecting Walton?s hand in friendship, Frankenstein reaffirms this fateful inability for social connection: ?you speak of new ties, and fresh affections? such is not my destiny? (215). In these final words, Frankenstein hints that in blindly pursuing his enterprise, he sacrificed his position in society forever.

Walton, on the other hand, seeks friendship, cares for his companions, and finds consolation in human society. After writing to his beloved sister, Mrs. Saville, ?I desire the company of a man,? he encounters a gaunt, grotesque Victor Frankenstein (19). Shelley deliberately compares Walton?s revival of Frankenstein to Frankenstein?s own creation of a man:

I never saw a man in so wretched a condition? We? restored him to animation? As soon as he showed signs of life we wrapped him up in blankets and placed him near the chimney of the kitchen stove. By slow degrees he recovered and ate a little soup, which restored him wonderfully? I removed him to my own cabin and attended on him as much as my duty would permit. I never saw a more interesting creature?I would not allow him to be tormented by [the shipmates?] idle curiosity, in a state of body and mind whose restoration evidently depended upon entire repose. (26?27)

Shelley immediately likens Frankenstein to his own creation through the word ?wretched,? and, in doing so, present an irony. Frankenstein deserts his ?wretched? creation, who then becomes hungry and harassed by society. But when the roles are reversed, and Frankenstein is described as ?wretched,? he is given ?soup,? shelter, and protection from being ?tormented.? Through this uncanny juxtaposition, Shelley presents Walton as far more friendly and empathetic than Frankenstein. In actively ?attend[ing] on the man he animates, Walton, unlike Frankenstein, feels emotional attachment: ?I begin to love him as a brother; and his constant and deep grief fills me with sympathy and compassion? (29). Another stark juxtaposition lies at the end of the novel when Walton?s ship is frozen into an ice sheet. He often expresses to Mrs. Saville a deep concern for the welfare of others: ?Be assured that for my own sake, as well as yours, I will not rashly encounter danger,? and ?I shall do nothing rashly: you know me sufficiently to confide in my prudence and considerateness whenever the safety of others is committed to my care? (22, 23). Accordingly, he consents to his crew?s request that the enterprise turn back toward England: ?in justice, I could not refuse? (216). Though Frankenstein declares, ?Do not return to your families with the stigma of disgrace marked on your brows. Return as heroes,? Walton feels a social duty which overcomes his thirst for glory (217). He reaffirms this value to Mrs. Saville: ?I have lost my hopes of utility and glory? I am wafted towards England, and towards you, I will not despond? I may there find consolation? (219, 220). Expressly deeply pained by his failed enterprise, Walton retains the ability to find solace in human communion.

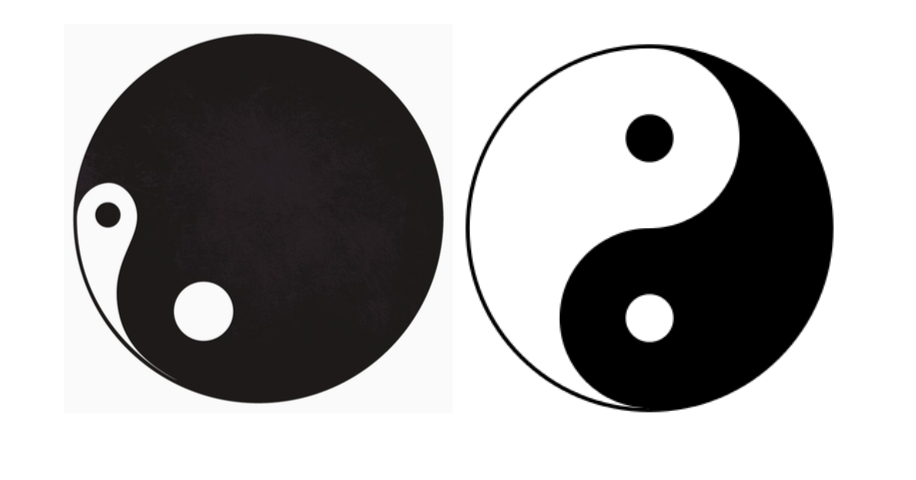

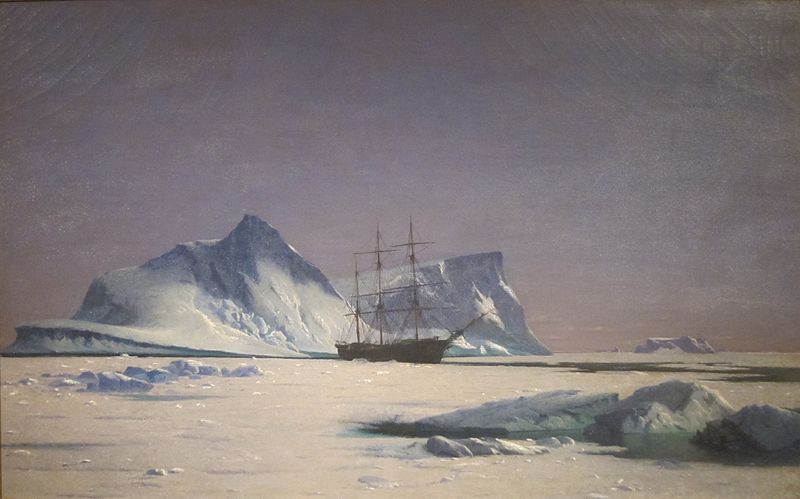

Frankenstein (Represented on Left) and Walton (Represented on Right)

Frankenstein (Represented on Left) and Walton (Represented on Right)

Though both men are similar in identity and enterprise, their treatment of friends precipitates starkly different fates; Walton survives to reconnect with society while Frankenstein meets a lonely demise. This pattern can be symbolized by yin-yang, ancient symbols which depict the relationship of opposing forces. In the context of Shelley?s novel, black represents isolation while white represents companionship. Frankenstein is consumed by isolation; his companionship with society is all but obliterated by the close of the story. Walton, on the other hand, represents the perfect balance of isolation and companionship. Though he does pursue an enterprise, he does not become wholly consumed by his isolationist ambition. Indeed, he strikes a compromise between isolation and society which ultimately forfeits his enterprise. This, Shelley contends, is necessary to humanity. For if enterprise goes unchecked and man isolates himself, both become an all consuming and destructive force ? almost like the black hole of Frankenstein?s yin yang. The rationale behind her proposition is expressed by Walton in an early letter to Mrs. Saville: ?I bitterly feel the want of a friend. I have no one near me? to approve or amend my plans. How would such a friend repair the faults of your poor brother!? (19). The Captain desires companionship to counterbalance the ?faults? of his zealous, isolationist ambition. Ironically, he seeks to become friends with Frankenstein, a man who has cast away all of his friends in favor of his enterprise. Forced together by chance, the sole communion between these two men leaves an indelible mark on Walton, teaching him the potential catastrophe of his unchecked ambition. This recognition is focal to Shelley?s ultimate message that isolation elicits humanity?s vices and social connection is humanity?s best protection against itself.

Elegantly woven into Frankenstein?s story, this critique of isolationism is a diatribe against Shelley?s contemporary society. At the height of the Romantic Era, she lived in a climate of stark gender separation. Often only joining for breakfast and dinner, man and woman were isolated in different social spheres. The ?woman sphere? consisted of domestic life ? cleaning, cooking, and child rearing. The ?man sphere? consisted of professional life ? studies, politics, and business. This separation was apparent in her own household: ?Not once did [Percy Shelley] help with domestic obligations. As the resident genius, he wandered in and out of the house at any time of day or night? ( Gordon) . Though Mary Shelley was a working author, a rare and unusual position for a woman, she felt this divide between herself and her husband. Through the guise of Victor Frankenstein, Shelley professed the danger of such gender isolation:

?I am now convinced that? if no man allowed any pursuit whatsoever to interfere with the tranquility of his domestic affections, Greece had not been enslaved, Caesar would have spared his country, Americavwould have been discovered more gradually, and the empires of Mexico and Peru had not been destroyed? (5 6 ).

In other words, Shelley conveyed that isolation from ?domestic affections,? or the sphere of woman, inevitably leads to violence and destruction . Just as Frankenstein professes this understanding to Walton, a man whose fate could potentially mirror his own, Shelley attempts to warn her peers and the younger generation to learn from the errors of earlier societies. In this respect, Frankenstein ?provid[ed] a cultural warning? [as it] subvert[ed] the exclusivity of the masculine voice, revealing it to be monstrously destructive?( Davis). Shelley affirmed that like the ambition of Victor Frankenstein, man?s sphere becomes dangerous when isolated from that of woman?s sphere. Like Walton?s yin yang, an intertwining balance was necessary between the two entities. Indeed, Shelley contended, the spheres must merge to achieve a harmonious society. Shelley?s Frankenstein is truly a monstrous tale as it holds up a mirror to humanity and calls attention to our own foibles. In this moment of national anxiety, our fate lies in our ability to learn from monsters.

Works Cited

Davis, James P. ?Frankenstein and the Subversion of the Masculine Voice.? Women?s Studies,

vol. 21, Routledge, June 1992, pp. 307?322, Academic Search Complete, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=19604089&site=ehost-live.

Gordon, Charlotte. ?Mary Shelley: Marlow and London [1817?1818].? Romantic Outlaws: the Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and Her Daughter Mary Shelley, Random House, New York, 2015, p. 247.

?Too Much Yin.? Redbubble, ih2.redbubble.net/image.11132141.7775/fc,800×800,white.jpg. ?Yin Yang.? All Free Download, Clipart, images.all-free-download.com/images/graphiclarge/yin_yang_clip_art_26469.jpg.