Was Ol? Blue Eyes really a made man?

Rumours of Frank Sinatra?s Mafia connections dogged his entire career. The evidence was rather more than just circumstantial?

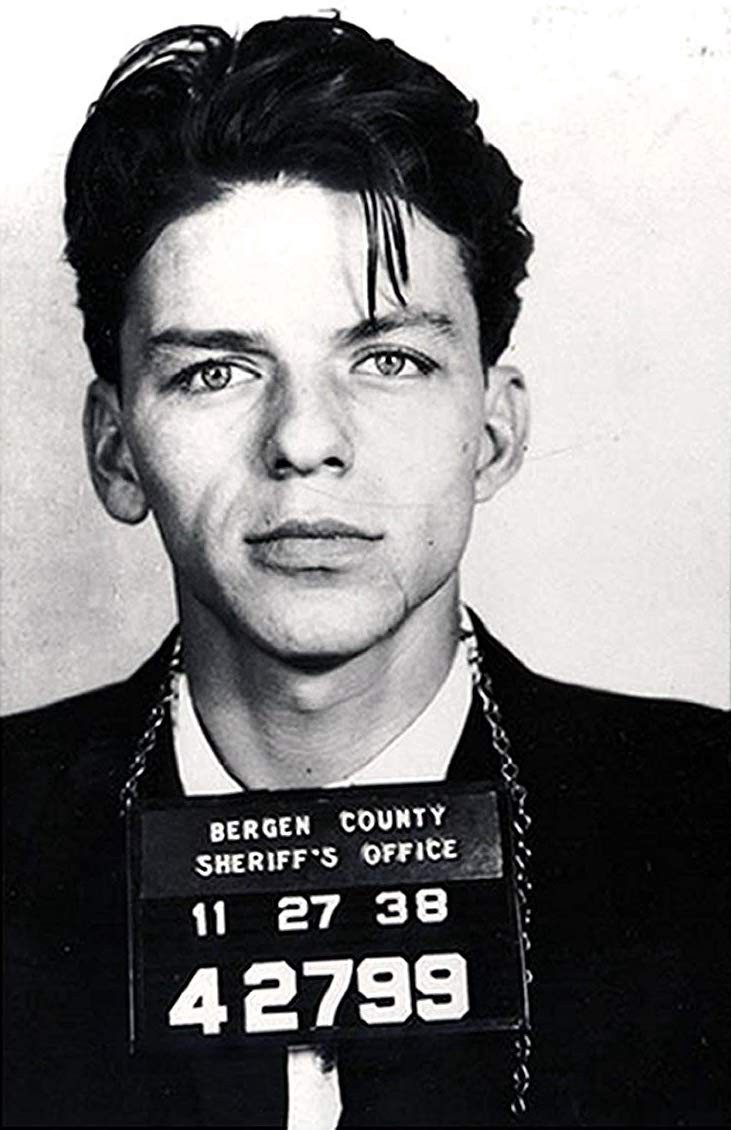

Sinatra in 1938, busted for adultery.

Sinatra in 1938, busted for adultery.

In 1950 the US Senate convened a committee to investigate organised crime in America. Popularly known as the Kefauver Committee, after its chairman Senator Estes Kefauver, its findings included admissions of the FBI?s failure to combat countrywide mob activity to date, leading to the creation of more than 70 local ?crime commissions? to harry the Mafia at local level, and a nationwide Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organisations Act. Unusually for the time, the proceedings were televised, with more than 30 million viewers tuning in to watch the testimonies of infamous gangsters: Mickey Cohen, Frank Costello, Jake ?Greasy Thumb? Guzik and others. Narrowly escaping a public grilling on this occasion was a struggling club singer called Frank Sinatra.

Council Joseph L. Nellis questioned the singer in advance to determine his suitability for the stand, and the Kefauver Committee ultimately decided that no real purpose would be served by a Sinatra subpoena: his career was ailing at the time, and the Committee generously opted not to finish him off by tarring him with the Mafia brush. But during his questioning Sinatra nevertheless admitted to more than passing acquaintances with a significant list of made men: Lucky Luciano, Bugsy Siegel, Willie Moretti and Al Capone?s cousins The Fischetti Brothers among them.

Sinatra would not escape similar hearings in the future. While he always denied any Mafia involvement, his name kept cropping up. He was called ? along with his fellow Rat Pack performer Sammy Davis Jr. ? before a Joint Senate-House Select Committee on Crime, investigating gambling and corruption related to sport, in 1972. And there was further public testimony, and further denials, in the hearings of the Nevada Gaming Control Board in 1981, where Sinatra was seeking to obtain a lucrative gambling license for his Las Vegas interests. They were never proven, but the whispers of Sinatra?s intimate links to the mob were never silenced either. Was he really part of the Mafia? Or was he, as many have concluded, just a ?groupie?, in love with the life but content to watch from the sidelines?

Possible Mafia ties stretch back to Sinatra?s grandfather?s youth in Sicily. The Italian island was the birthplace of the Cosa Nostra. Frank?s grandfather Francesco Sinatra was born in 1857 in the hill town of Lercara Friddi: Mafia heartland only about fifteen miles from the famous Corleone. While there?s no evidence that Francesco was actually involved in any dubious undertakings, he lived on the same street as the Luciano family, whose most famous son Salvatore ? nicknamed Lucky ? would come to be considered the father of organised crime in New York in years to come. Lucky?s address book even contained the name of one of Francesco?s in-laws, so it?s entirely possible that Francesco and the Lucianos were personally acquainted.

Frank Sinatra, 1920s

Frank Sinatra, 1920s

Francesco Sinatra emigrated to New York in 1900 with his wife and five children. The young Antonino, Frank?s father, grew up first to become an apprentice shoemaker, but also worked as a chauffeur and a professional bantamweight boxer. He had run-ins with the law involving a hit-and-run accident (for which he narrowly escaped a manslaughter conviction) and for receiving stolen goods. He married Frank?s mother Dolly in 1913, and Frank himself was born, an only child, two years later. Dolly was a midwife, known to some as ?Hatpin Dolly? due to her notoriety for performing illegal backstreet abortions (she was convicted twice). But she was also heavily involved in local Hoboken and Jersey City politics, working for two successive mayors at a time when the boroughs were infamous for corruption. When she and Antonino opened a bar in 1917, she became well known for bouncing drunks with her ever-present billy club.

The bar was the environment in which the young Frank Sinatra grew up, at a time when selling alcohol was illegal thanks to America?s Prohibition laws. Frank would be doing his homework in the evenings in the corner of an establishment that could only remain in business thanks to his father?s bootlegging activities with the local gangster Waxey Gordon, who in turn was connected to Lucky Luciano. Hoboken, as a port town, was a major transit point for illicit alcohol shipments, and Frank?s uncles, Dolly?s brothers, were also heavily embroiled in the trade. Prohibition, perversely, was big business if you were on the wrong side of the law. It was the making of the Mafia in America. Frank?s upbringing certainly wasn?t wracked with hardship: his family rode out the Great Depression of the 1930s to the extent that Dolly bought him a brand new car for his 15th birthday.

Frank, however, despite his constant exposure to mob activities, seized on a different ?racket? very early in life. He gave his first public performances singing along to the player piano in the Sinatra Bar and Grill, at the age of about eight. Misty-eyed tough guys would give him pocket money for his renditions of sentimental popular songs of the day, and a future star was born.

The Hoboken Four, recorded for NBC Radio in 1935.

His first professional break as a singer came in 1935 when he was 20, as a member of local singing group The Hoboken Four (they were a trio until Dolly leaned on them to let Frank join). This led to years of singing in clubs and bars in New York and around the country: an occupation in which fraternising with mobsters and their bosses would have been completely unavoidable. Organised crime went hand-in-hand with the bar business, and even after Prohibition ended, the mob remained silent partners in many businesses. They were also heavily involved in the music industry, controlling most of the jukeboxes nationwide, and therefore dictating what records would be successful.

?Saloons are not run by the Christian Brotherhood,? Sinatra hedged in later life. ?A lot of guys were around that had come out of Prohibition and ran pretty good saloons. I worked in places that were open. They paid. They came backstage. They said hello. They offered you a drink. If St Francis of Assisi was a singer and worked in saloons he?d have met the same guys. That doesn?t make him part of something??

Gangster-chic Sinatra, photographed in 1941 by Murray Garrett.

Gangster-chic Sinatra, photographed in 1941 by Murray Garrett.

Sinatra enjoyed a very good year in 1939 ? he had a contract with bandleader Tommy Dorsey, a hot enough act for Sinatra?s national profile to be hugely increased. In his first year with Dorsey Sinatra recorded more than forty songs and topped the charts for two solid months with ?I?ll Never Smile Again?. But Sinatra?s relationship with Dorsey was a troubled one, and their parting ways in 1942 began the first public rumblings of Sinatra?s possible Mafia connections.

With his profile on the increase, Sinatra was keen to go solo, but Dorsey refused to release him from a contract that still had years to run: he was being well-paid but his career was not his own. If he broke his contract he would owe considerable chunks of his income to Dorsey for the next decade: a clause Sinatra naturally found unsavoury. Lawyers failed to find any loopholes in the deal that would allow Sinatra to walk free, and Dorsey remained steadfast in his resolve to keep his biggest star, until he was persuaded otherwise from a more sinister angle than the law. Sinatra always denied it, but Dorsey?s version of the story was that he found himself visited by Willie Moretti and two sharp-suited henchmen. ?Willie fingered a gun and told me he was glad to hear I was letting Frank out of our deal,? Dorsey recalled. ?I took the hint.?

The next years saw ?Sinatramania? across the USA, as the singer recorded hit after hit, played to sell-out crowds, caused near-riots wherever he went, became a ubiquitous presence on television and launched a film career. But there was also resentment as, with the advent of the Second World War, he somehow avoided military service. Rumours were rife that he had paid his way out of the war ? although the FBI never found any evidence of this ? while other sources suggest he was deemed unfit both on psychological grounds and because of a perforated eardrum. Whatever the reason, pictures of him at home as the war raged in Europe, surrounded by beautiful women and living the superstar lifestyle, did not endear him to those in uniform and their families.

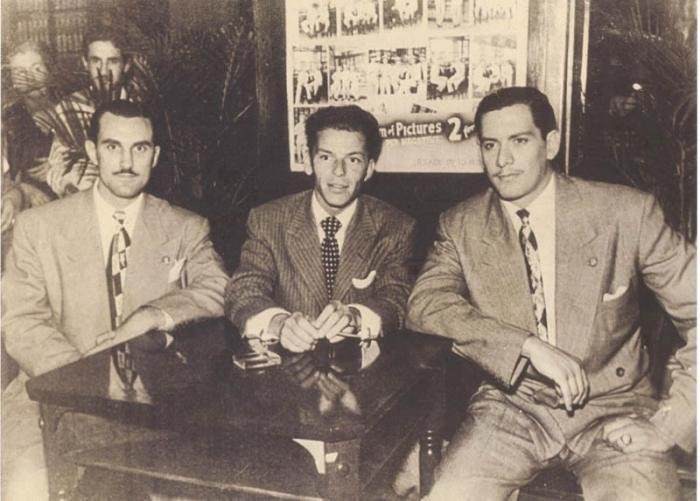

Sinatra with the Fischetti Brothers.

Sinatra with the Fischetti Brothers.

That controversy was as nothing, however, to the furore that erupted when Sinatra was photographed in Cuba in 1947 at a mob celebration for Lucky Luciano?s release from jail. The incriminating pictures showed Sinatra with his arm around Luciano on a hotel balcony; with Luciano at a Havana nightclub, as usual surrounded by babes; and with the Fischetti Brothers at the airport, disembarking a plane with a valise in hand. Why would he have been carrying his own case? Comedian and movie star Jerry Lewis later alleged that Sinatra used to carry money for the mob. Sinatra claimed the case was full of art supplies, and that he couldn?t have physically carried the $2m he was accused of trafficking out of the US. Journalist Norman Mailer quickly established that considerably more than $2m fits easily in an attach.

Rumours for the reasons aside, Sinatra?s presence at the mob shindig was inarguable. Sinatra was close to Joe Fiscetti, who was a talent agent for mob-owned clubs all over America, and had agreed to the impromptu Havana trip while holidaying with his wife Nancy across the water in Miami. Once in Cuba, Sinatra claimed, he learned the embarrassing truth that he was ensconced at a Mafia convention, and reasoned it would be impolite ? not to say dangerous ? to make excuses and leave. He stayed and performed for the goodfellas, but several witnesses confirmed that he displayed little reserve in accepting the mob?s hospitality, which included hotel room orgies with ?planeloads? of call girls. It was almost as if Sinatra felt right at home, and many of his Havana acquaintances would remain with him during his Las Vegas years.

The Godfather?s Johnny Fontane (Al Martino) was inspired by Sinatra.

Before that, however, came the doldrums, as Sinatra?s star began to wane in the US, outshone by younger up-and-comers like teen heartthrob Eddie Fisher. Sinatra, now in his 30s, failed to launch the successful television career he?d hoped for, and actually attempted suicide in 1951. But he achieved one of the greatest comebacks of all time when he landed the starring role in the 1953 movie From Here To Eternity, for which he won an Oscar. And once again, evidence suggests he didn?t achieve that success entirely on merit. The head of Columbia Studios, Harry Cohn, had been adamant that Sinatra would not be cast in the film, until a phone call from gangster Johnny Roselli persuaded him it was in his best interests after all. The alleged episode was the inspiration for Mario Puzo in his novel The Godfather (and Francis Ford Coppola?s subsequent film), for the part in which studio head Jack Woltz is terrorised into casting Johnny Fontane in his movie. Sinatra was furious, but still lobbied (unsuccessfully, obviously) for Marlon Brando?s role when The Godfather was being cast.

Having helped Frank revive his career, it was unlikely that the mob would let him out of their clutches. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover famously described Sinatra having a ?hoodlum complex?, and it?s clear that he relished the dark glamour of associating with gangsters and criminals, and enjoyed their protection. The fact was also, however, that he was as much in thrall to the Mafia as he would have been to Tommy Dorsey if he?d failed to break his contract. When they asked him for free performances in support of one of their causes, he would jump to oblige, and in 1953 when Mafia fortunes were being invested in making Las Vegas the gambling capital of the world, Sinatra was an important pawn in their game. If Vegas was to attract visitors, it needed a roster of star attractions and performers. Sinatra was to be a regular fixture at the mob-run Sands Hotel and Casino, in return for a 2% stake in the business.

Left to right: Gregory DePalma, Sinatra, Thomas Marson, Carlo Gambino

Left to right: Gregory DePalma, Sinatra, Thomas Marson, Carlo Gambino

The Sands became his home away from home until the late 60s, and in the mid-70s another incriminating photograph would haunt him through the media: he was snapped backstage at the mob-built Westchester Premier Theatre in New York, palling around with crime boss Carlo Gambino, capo Gregory DePalma, West Coast mobster Thomas Marson and others. The FBI kept a file open on Sinatra for five decades until his death in 1998.

Sinatra dressed like a gangster, talked like a gangster, behaved like a gangster, grew up around gangsters and fraternised with gangsters. Perhaps the greatest irony is that he was never actually a made man. His relationship with the mob was clearly beneficial to both sides: Sinatra got fame and fortune and the mob had a tame star who could be used to boost their coffers and shore up their investments when necessary. If Sinatra was instrumental in establishing Las Vegas, Las Vegas was equally important in his 1950s comeback, but while the singer was clearly starstruck by the mob, it?s unclear whether the mob was similarly dazzled, or simply saw Sinatra as expedient as long as he behaved. ?I?d rather be a don for the Mafia than president of the United States,? is a quote often attributed to the singer. If that?s true, it seems that he never really got His Way after all.

This feature was originally published in All About History magazine in 2014.