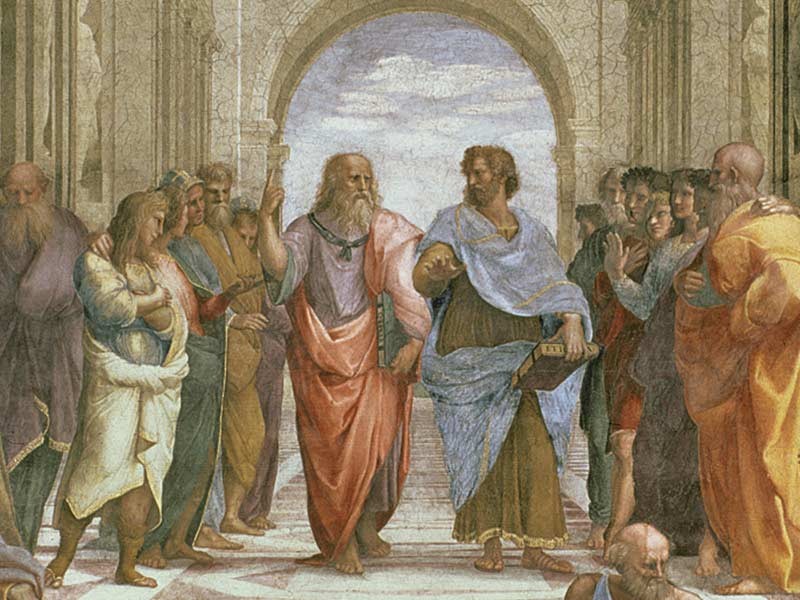

The allegory of the cave is one of the most famous passages in the history of Western philosophy. It is a short excerpt from the beginning of book seven of Plato?s book, The Republic. Plato tells the allegory in the context of education; it is ultimately about the nature of philosophical education, and it offers an insight into Plato?s view of education. Socrates is the main character in The Republic, and he tells the allegory of the cave to Glaucon, who is one of Plato?s brothers.

In book seven of The Republic, Socrates tells Glaucon, who is his interlocutor, to imagine a group of prisoners who have been chained since they were children in an underground cave. Their hands, feet, and necks are chained so that they are unable to move. All they can see in front of them, for their entire lives, is the back wall of the cave. Socrates says:

Some way off, behind and higher up, a fire is burning, and between the fire and the prisoners above them runs a road, in front of which a curtain wall has been built, like a screen at puppet shows between the operators and their audience, above which they show their puppets.[1]

So, there are men, who pass by the walkway and carry objects made of stone behind the curtain-wall, and they make sounds to go along with the objects. These objects are projected onto the back wall of the cave for the prisoners to see. The prisoners come up with names for the objects; they are interpreting their world intelligible to them. Hence, it is almost as though the prisoners are watching a puppet show for their entire lives. This is what the prisoners think is real because this is all they have ever experienced; reality for them is a puppet show on the wall of a cave, created by shadows of objects and figures.

Socrates goes on to say that one of the prisoners somehow breaks free of those chains. Then he is forced to turn around and look at the fire, which represents enlightenment; recognising your ignorance. The light of the fire hurts his eyes and makes him immediately want to turn back around and ?retreat to the things which he could see properly, which he would think really clearer than the things being shown him.?[2] In other words, Socrates is stating that the prisoner does not want to progress in the way he sees things, and his understanding of reality. However, after his eyes adjust to the firelight, reluctantly and with great difficulty he is forced to progress out of the cave and into the sunlight, which is a painful process; this represents a different state of understanding. Plato uses light as a metaphor for our understanding, and our ability to conceive of the truth. So the prisoner progressed past the realm of the firelight, and now into the realm of sunlight. The first thing he would find easiest to look at is the shadows, and then reflections of men and objects in the water, and then finally the prisoner is able to look at the sun itself which he realises is the source of the reflections. When he finally looks at the sun he sees the truth of everything and begins to feel sorry for his fellow prisoner?s who are still stuck in the cave. So, he goes back into the cave and tries to tell his fellow prisoners the truth about reality, but the prisoners think that he is dangerous because he has come back and upset everyone?s conformist opinion about things. The prisoners do not want to be free because they are comfortable in their own ignorance, and they are hostile to people who want to give them more information. Therefore, Plato is suggesting that ?your philosophical journey sometimes may lead your thinking in directions that society does not support.?[3]

The allegory of the cave is an extended metaphor and it provides an insight into Plato?s view of education. The people in the cave represent us as a society, and Plato is suggesting that we are the prisoners in the cave looking at only the shadows of things. However, the cave also represents the state of humans; we all begin in the cave.[4] According to Ronald Nash, Plato believed that:

Like the prisoners chained in the cave, each human being perceives a physical world that is but a poor imitation of a more real world. But every so often, one of the prisoners gets free from the shackles of sense experience, turns around, and sees the light![5]

Plato uses the cave to symbolise a physical world; a world in which things are not always what they seem to be, and there is a lot more to it than people think there is. The outside world is represented as the world of ideas, thoughts, and reality ? by the world of Ideas, Plato is talking about the non-physical forms, and that these non-physical forms represent a higher, more accurate reality. In other words, ?according to Plato, our senses are only picking up shadows of the true reality, the reality of forms or ideas. This reality can only be accurately discerned through reason, not the physical senses.?[6]

The process of progressing out of the cave is about getting educated and it is a difficult process; in fact it requires assistance and sometimes force. Here Plato is implying that when getting an education there is a struggle involved. He is telling us about our struggle to see the truth, and to be critical thinkers. We want to resist; ignorance is bliss in many ways because knowing the truth can be a painful experience, so in some ways it is easier to be ignorant. The person who is leaving the cave is questioning his beliefs, whereas the people in the cave just accepted what they were shown, they did not think about or question it; in other words, they are passive observers.

The allegory of the cave shows us the relation between education and truth. For Plato, the essential function of education is not to give us truths but to dispose us towards the truth. But not all education need necessarily be about the truth. It can be seen as capacity building:

One purpose of the allegory of the cave is to show that there are different levels of human awareness, ascending from sense perception to a rational knowledge of the Forms and eventually to the highest knowledge of all, the knowledge of the Good.[7]

According to Plato, education is seeing things differently. Therefore, as our conception of truth changes, so will our education. He believed that we all have the capacity to learn but not everyone has the desire to learn; desire and resistance are important in education because you have to be willing to learn the truth although it will be hard to accept at times.

The people who were carrying the objects across the walkway, which projected shadows on the wall, represent the authority of today, such as the government, religious leaders, teachers, the media etc. ? they influence the opinions of people and determine the beliefs and attitudes of people in society. The person who forced the prisoner out of the cave and guided them could be interpreted as a teacher. Socrates compares a teacher to a midwife, for example, a midwife does not give birth for the person, however a midwife has seen a lot of people give birth and coached a lot of people through it, similarly, a teacher does not get an education for the student, but can guide students towards the truth:

Socrates as a teacher is a ?midwife? who does not himself bring forth truth, but rather by means of his questioning causes the learner to rationally apprehend, or give birth to, as it were, truths that were already gestating within.[8]

So, the teacher in the allegory of the cave guided the prisoner from the darkness and into the light (light represents truth); education involves seeing the truth. Plato believed that you have to desire to learn new things; if people do not desire to learn what is true, then you cannot force them to learn. The prisoner had to have the desire and persistence to learn. In the same way, students themselves have to be active ? nobody can get an education for you; you have to get it for yourself, and this will sometimes be a painful process. A teacher can fill students with facts, but it is up to the student to understand them. According to Plato, a teacher?s job is to lead you somewhere, and to make you question your beliefs so that you can come to your own conclusion about things; thus, education is a personal journey.

Plato makes clear that education where students are passively receiving knowledge from professors is wrong. What the allegory has shown is that:

[?] the power and capacity of learning exists in the soul already; and that just as the eye was unable to turn from darkness to light without the whole body, so to the instrument of knowledge can only by the movement of the whole soul be turned from the world of becoming into that of being [?][9]

Plato says that philosophical education requires a reorientation of the whole self; it is a transformative experience. He believed that education is not just a matter of changing ideas or changing some practices, it is a process that transforms ones entire life because it involves the turning around of the soul. Education is the movement of the self, the transformation of the self. For example, in order for the prisoners to learn they had to not only turn their head around, but also turn their whole body around which included their soul, and passions in their mind, to educate themselves.

Therefore, education is a complete transformation of ones value system; ?it requires a ?turning around? and ?ascent? of the soul ? what we might call a spiritual awakening, or the finding and following of a spiritual path.?[10] By this, Plato means seeing the world in a different way, in the correct way.

In conclusion, Plato appears to be suggesting that we need to force ourselves to want to learn about the truth. Seeking knowledge is not an easy journey; it is a struggle, and once you see the world differently you cannot go back. For example, when the prisoner turned around he realised that the shadows on the wall were less real than the objects in the back that were casting the shadows; what he thought was real all his life was merely an illusion. If the prisoner did not question his beliefs about the shadows on the wall, he would never have discovered the truth. Hence, Plato believes that critical thinking is vital in education. When you try to tell others about the truth, they will not always accept it, as people are often happy in their ignorance. In the allegory of the cave the prisoner had to be forced to learn at times; for Plato, education in any form requires resistance, and with resistance comes force.

In a way Plato manipulates the reader as he implies that we are prisoners, however we believe that we are not prisoners ? this makes us want to learn and search for the truth. It is easier not to challenge ourselves, and not be challenged by others. It is easier to just sit there and watch the puppet show, and not question your beliefs. It is difficult to turn around, however the rewards of making that journey are great, as the allegory of the cave tells us.

For Plato, education is personal and it is the transition from darkness to light, where light represents knowledge and truth. He believed that everyone is capable of learning, but it is down to whether the person desires to learn or not. The people in the cave needed to desire an education with their whole body and soul; thus, education is the formation of character, which involves the turning around of the soul.

Follow Thoughts and Ideas on Facebook: facebook.com/thoughtsandideas1

[1] Plato: The Republic 514b

[2] Plato: The Republic 515e

[3] Manuel Velasquez: Philosophy: A Text with Readings p. 6.

[4] Julia Annas: An Introduction to Plato?s Republic pp. 252?253

[5] Ronald H. Nash: Life?s Ultimate Questions: An Introduction to Philosophy p. 94.

[6] Kenneth Allan: Contemporary Social and Sociological Theory: Visualizing Social Worlds p. 8.

[7] Ronald H. Nash: Life?s Ultimate Questions: An Introduction to Philosophy p. 95.

[8] Ann Ward: Socrates: Reason or Unreason as the Foundation of European Identity p. 171.

[9] Plato: The Allegory of the Cave p. 12.

[10] Carr et al: Spirituality, Philosophy and Education p. 98.