And if they don?t, how should we live our lives?

Slavery is good.

Your instant reaction is to strongly disagree with that statement. Slavery was a historical atrocity we are still making amends for today. When we look back at history, we?re astonished that people could have been so cruel and backwards. We?re glad that the world has become enlightened enough to get rid of such a horrible practice.

Now consider this statement.

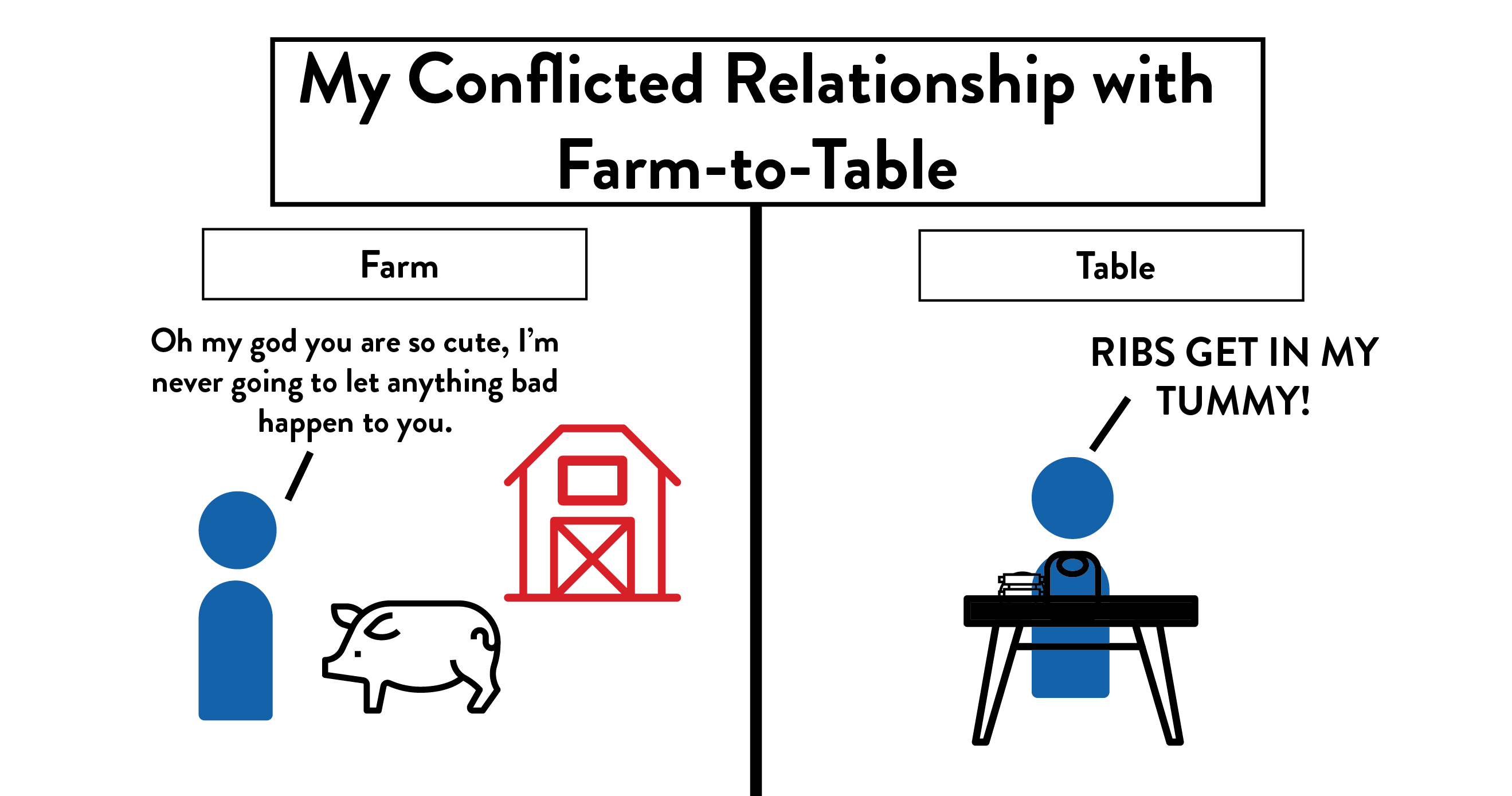

Eating meat is perfectly acceptable.

Most of you agree with it. And while you may not necessarily be proud of your ability to scarf down a 36oz Tomahawk steak, you have no problems with eating animals. This is just the natural order of things. Humans are the apex predator and it?s our right to eat meat.

These two statements showcase our morality ? our inherent feeling that certain actions are right and other actions are wrong. But where does our sense of morality come from? Why is eating meat acceptable while slavery is not? Don?t they both take advantage of other living beings?

One rationale is that slavery is immoral because it abuses human beings while eating meat is okay because it is only involves animals. But who drew that distinction? Why do we treat humans as special even though many animals we consume have proven to be extremely intelligent.

Some of you may believe that ?it just is.? Enslaving other humans is a self-evident wrong because it feels wrong while eating animals is okay because it doesn?t trigger the same moral disgust.

But keep in mind that slavery used to be common across the world. Slaves built our pyramids, grew our crops and fed our cattle. The founding fathers of the US ? as they proclaimed the inalienable rights of man in the Declaration of Independence? kept slaves. The unfortunate truth is that the world we know was built by millions of slaves. It?s only in relatively recent times that we see slavery as abhorrent. If you were transported back two hundred years and were lucky enough to be a white land-owning male, you wouldn?t have given the morality of slavery a second thought.

So unless we truly believe that the millions of people who have ever owned slaves didn?t have a shred of the decency in them, we are forced to acknowledge that what is considered morally acceptable has changed over time.

Even today we don?t all agree on what ?right? is. Parts of the world still believe women belong in the household, the punishment for stealing is hand-chopping, and that 8 year-olds need to support their families through a factory job. I?m sure many of you instinctually view these practices as barbaric, I know I do. But who are we to impose our sense of morality on the rest of the world?

I?m not here to convince you that eating meat is morally wrong or that slavery is morally comparable. I eat meat. I?m also definitely not advocating for the spread of slavery, hand-chopping, or child labor in any form. But I hope you see how much we take our sense of morality for granted. We treat our ability to distinguish between ?right? and ?wrong? as gospel despite the fact that ?right? and ?wrong? has changed so much across time and cultures.

That?s because morality ? our ability to separate right from wrong ? doesn?t really exist.

Or, at least not in the way of things that we typically think of existing.

THINGS THAT EXIST AND THINGS THAT DON?T

Here are some things that exist:

1. 2+2 = 4

2. That rock over there.

3. The bed I am currently lying on.

They exist, because regardless of whether I, you, or anyone else believes in them, they would go on existing. If every person disappeared off the Earth tomorrow, 2+2 would still equal 4, that rock will still be there, and my bed will still be here, albeit empty. The statements above exist independently of humans. Things that truly exist are bound by the rules of nature which are logical and consistent. If I drop a rock on earth it will always fall at an accelerating rate of 9.8 m/s2 no matter where I am, who I am with, and what year it is.

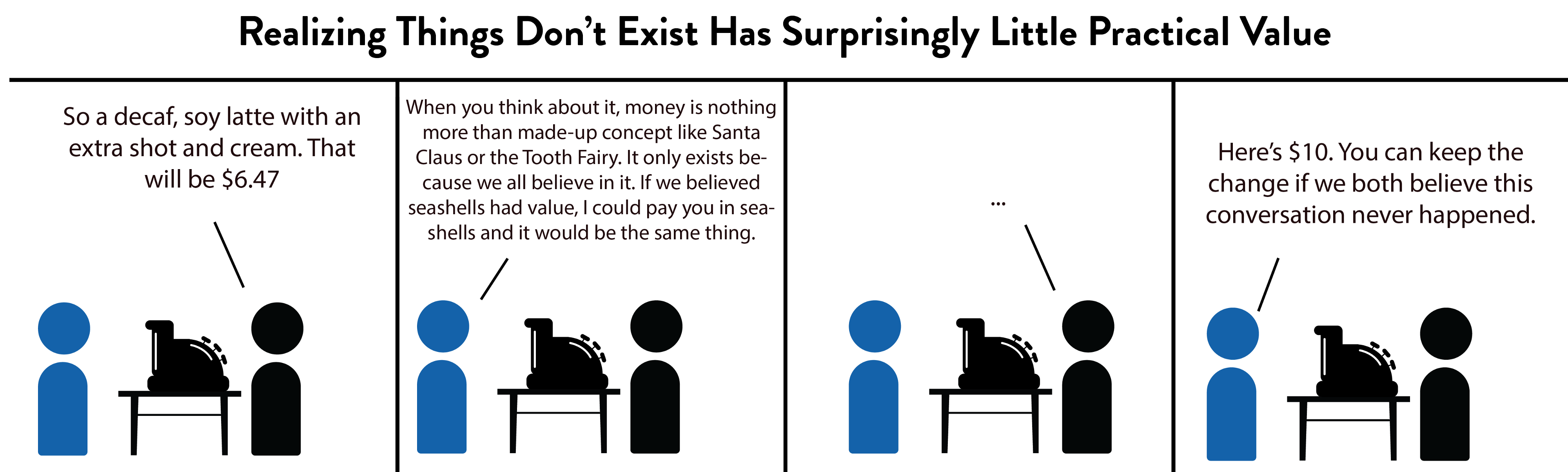

Contrast that to a concept such as money. It doesn?t truly exist in reality but only lives in our heads. Yes, the physical, paper, aspect of money exists; but the monetary value of money is something we made up. When I give Starbucks a $5 bill for a coffee I can?t pronounce, I am giving them a piece of paper that me, Starbucks, and the rest of the world has collectively agreed to be equal to the concept of ?5 Dollars.? If everyone disappeared off Earth tomorrow, that $5 bill would just be a crumpled piece of paper.

Things that only live in our heads are dependent on our beliefs ? there are no objective truths. There is no fixed logic to money the same way 2+2 = 4. That?s why you can believe a painting is worth $100 while I believe it belongs in the trash. That?s why a $1 bill can be converted to 6 yuan one day, 6.5 yuan the next day, and 5.5 yuan the day after that. Concepts in our head survive because of our beliefs, so when our beliefs change, the concepts change as well.

Much of our lives revolves around concepts that only reside in our minds. The concepts just feel like they truly exist because the beliefs are usually shared by most of the population. Here are three examples:

Marriage is just a belief that two people share a special relationship.

Mickey Mouse is just a belief in a cartoon mouse that has big ears.

Companies are just a belief that a group of people, symbols, and machinery is somehow more than the combined parts.

Like money, all three concepts are made-up. If everyone in the world stopped believing in them, they would instantly vanish.

That?s basically what divorce is. Previously two individuals, their friends, families, and the government believed that the two people had a special relationship called ?marriage?. Divorce is just a formal way for all parties to simultaneously abandon that belief.

It?s important to separate things that actually exist in reality from concepts that only exist in our minds because morality ? principles distinguishing right from wrong ? falls squarely in the latter category. And like all concepts that only exist in our minds, our sense of morality isn?t bound by rational natural laws, but by our irrational fickle brains.

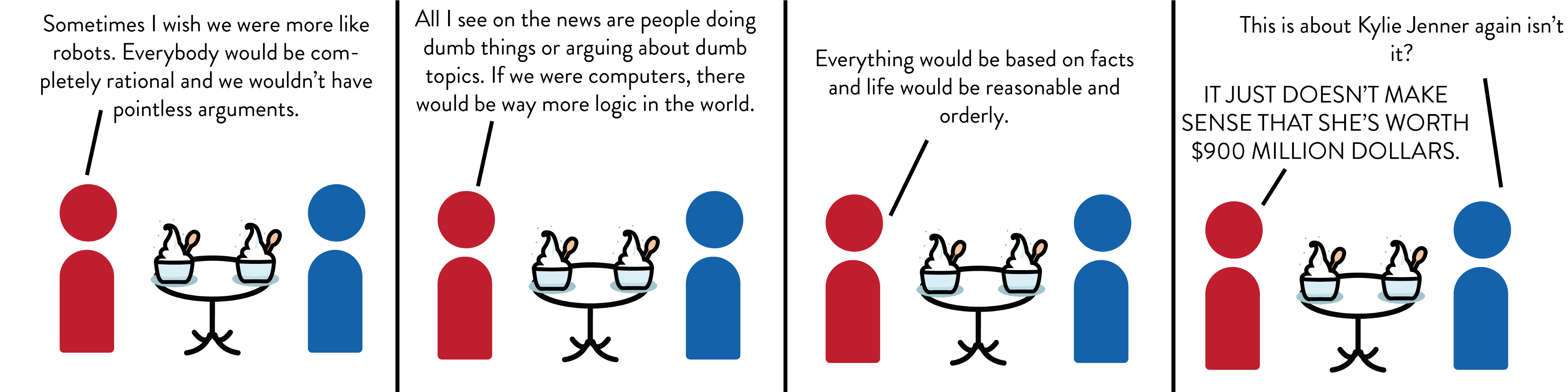

We are not rational. Most of our decisions are guided by unconscious impulses, emotions, and the environment we make them in. In nature, if A > B, and B > C, then A must be greater than C. And as long as A, B, and C don?t change, it will always be this way. But studies have shown again and again how humans break logical laws in our decision making depending on the environment we are in, who we are with, and how hungry we are.

As a result, concepts that only exist in our minds, such as morality, beauty, humor, and justice, are subject to the same irrationality. There aren?t defined logical principles governing these concepts the way there are for natural subjects such as chemistry or physics. Mix baking soda and vinegar and you?ll always get a chemical reaction perfect for a 3rd grade science experiment. Tell a joke, and your audiences? reaction will depend on the mood they are in, the time of day, where they are, and thousands of other factors. Even though there are some jokes most people find funny, there aren?t universal laws that apply to everyone. This is why I can find Conan O?Brien hilarious while you prefer Jimmy Fallon.

Morality is no different. Although there are generally shared beliefs that guide our actions (e.g. killing is bad), the beliefs are more like guidelines than rules. Thought experiments such as the infamous trolley problem and political issues such as the death penalty are so captivating precisely because there is no ?right? answer. We determine ?right? and ?wrong? based off constantly changing emotions and unconscious factors (e.g. what people around us think). We don?t determine right and wrong based off a set of unwavering principles like those found in nature. This is why our position on moral topics can feel conflicted and change day-to-day. This is also why slavery was morally acceptable hundreds of years ago but no longer is today. The concept of morality lives entirely in our heads so when our beliefs about how to treat other humans changed, our view on slavery changed as well.

So if morality doesn?t exist, how should we live our lives? Do we go on a crime spree now that we know right and wrong are made-up? Unfortunately, no. To understand why, let?s understand where morality comes from.

PRODUCTS OF EVOLUTION

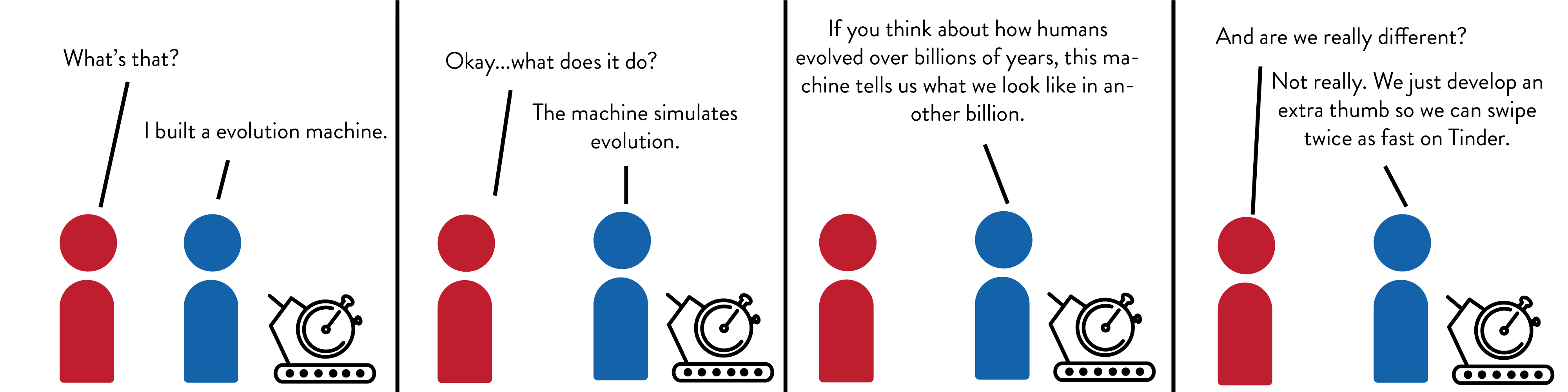

We are the products of evolution. Most of us intellectually know this, but don?t fully appreciate its implications. Our evolutionary origins explain how we live, think, and behave today.

The general idea is that organisms pass on genes from one generation to the next. Along the way, mutations occur. Most mutations have negative or neutral effects, but a select few increase the organism?s chances of passing their genes to the next generation. Over time, successful genes spread until they become the norm. And over billions of years, beneficial mutations compound with one another such that the single-celled organisms drifting around the ocean billions of years ago evolved into the hairy, multi-celled, froyo-loving mammals reading and writing this article.

This means that everything we do ? reading, eating, talking, buying digital watches ? is a result of evolution. I?m not saying our ancestors evolved to drive Ford F150s or swipe right on Tinder, but we evolved the physical capabilities and mental flexibility to handle these technologies.

We need to view our moral sense through the same evolutionary lens. Some of our moral sense is innate. Babies as young as 2 can recognize injustice and unfairness. But the majority of our moral sense comes from our environment and how we were raised.

Immediately after being born, our environment shapes our sense of morality through interactions with family, friends and culture. Sometimes we were taught explicitly (e.g. your mom telling you to ?Always share?); other times we learned implicitly (e.g. when your sister cried when you took her stuffed animal).

Our sense of morality becomes so ingrained in us that we aren?t conscious of the drivers behind our thoughts. We just get a tug of emotion, such as pity from watching an ASPCA commercial, that propels us into action (and open our wallets). Explaining our behavior with reasons only comes after we?ve already unconsciously decided what to do. And not just us, every person around the world lives their lives based on the same forces.

However, because morality is just a shared belief, there are no objectively true moral principles. Parts of our morality are similar across history and culture, but there are also differences. Grow up in the Northeast with liberal parents and your sense of morality will differ than if you grew up in the South with parents that voted Reagan into the White House. We all have a sense of ?right? and ?wrong? but we don?t always agree on what ?right? and ?wrong? is.

So even though we can recognize that morality doesn?t truly exist, we can?t escape the morality instilled in us. If I kick a dog when nobody is around to see it, it is not objectively ?wrong? because nothing is objective when it comes to morality. However, I will still feel tremendously guilty because a combination of evolution and my upbringing conditioned me to feel this way.

SO WHAT?

?Well that?s unhelpful? you may be thinking, ?I?ve read up to this point just to understand that morality doesn?t exist but I still have to act like it does??

But truly understanding the nature of morality affects how we view and take control of our lives.

When we accept that morality is nothing more than an evolutionary feature shaped by our upbringing, we realize how grey the world really is. There is no almighty scale judging the morality of our actions. Yes, our actions have external consequences, but the only person that determines our action?s moral ?rightness? is the person we face in the mirror every day.

Up to now, we took our moral sense for granted. But recognizing the true nature of morality means we can take control and shape our morality going forward. We can actively define our morality rather than passively accept the morality passed to us.

Making this transition requires recognizing the limits of our ingrained morality. We need to recognize that what feels morally right isn?t always right. Especially since morally right doesn?t truly exist.

Our ingrained moral sense usually works well. We avoid harming other people, try to be fair, and strive to be kind. These instincts line up with what most people consider the ?right? moral principles and are instincts we would have chosen for ourselves if we had the choice.

But we get into trouble when our moral sense doesn?t match society?s, especially around controversial issues such as abortion, death penalty, same-sex marriage, etc.

Our ingrained moral sense automatically pushes us toward a position that feels emotionally justified. We then come up with rational-sounding arguments to defend our side even though we already made up our mind. We?re incensed by people who disagree with us. ?Don?t they have a sense of decency?? we ask ourselves. ?How can they not feel how I feel about this issue?? We write impassioned Facebook posts and get into heated arguments with our in-laws. At the core, we believe that our moral position is justified because it just feels so right.

But when we recognize that our feelings are an evolutionary feature and don?t come from a higher truth, we realize that emotions-based decision making isn?t always the best course. Being an active moral participant means admitting that our emotions are not infallible. It also means understanding that the morality from which our emotions come from are based off our circumstances. Those with opposing views likely come from different backgrounds.

By acknowledging this, we start to treat morality like an opinion.

We reframe how we view morality from a fact to an opinion. Unlike facts, opinions differ by person, change over time, and don?t always make logical sense. You can have a difference in opinion with someone without thinking they are wrong or stupid.

Opinions are also not binary. You can believe that women should have the right to get an abortion while simultaneously feel guilty about the cost of unborn lives. You can place value on the life of a death row inmate while also recognizing the need for justice. You can feel sadness at the lives lost to mass-school shootings while also respecting our desire to protect ourselves through guns.

Most importantly, treating morality like an opinion allows us to say ?I don?t know.? Facts don?t conflict with one another but opinions do. And sometimes our moral opinions are so conflicted that it?s difficult to take a concrete position. Once we accept that there is no objectively ?right,? being undecided on issues is a perfectly acceptable position to take.

Making that acknowledgement leads to the final step to being an active moral participant: stop arguing with people and start listening. Once we acknowledge that a ?right? answer doesn?t exist, we?ll spend less time pointlessly trying to convince someone else why we?re right, and more time listening to their side. Even though our emotions may flare up in disagreement at what the other person is saying, we now know that our emotions are not foolproof.

After listening to a different viewpoint, we don?t have to change our minds. In fact, in most cases, I wouldn?t expect us to because going against our ingrained morality is very difficult. But at least we are one step closer to being an active participant in defining our morality. Rather than simply accept the morality handed to us, we made a conscious effort to open ourselves up to other perspectives. We wasted less energy trying prove a ?right? that doesn?t exist and spent more time connecting with another person. I think that?s as close to a true morally right as we will ever get.

Other Articles You May Enjoy

If you liked this article, visit LateNightFroyo.com to read about topics that spark conversations around love, life, and more.

When is the Right Time to Show up to a Party?

How Do You Get Out of Going Out?

How Young is Too Young to Date?