Listen to this story

–:–

–:–

Circadian rhythms? lesser know cousins may hold the key to a more fruitful day

Source: Unsplash

Source: Unsplash

The Cycles of our Nature

?every organism ? from paramecium to pachyderm ? is born, lives out its days, and dies influenced by a complex web of rhythms interwoven in time.? ? Ernest Rossi, The 20-Minute Break

Science has discovered a number of biological rhythms that play out in our lives on scales both large and small. This field of study is called chronobiology, underscoring the intricate relationship between our biological rhythms and time itself.

By understanding how these internal rhythms operate, we can learn to use them to our advantage.

Many people are probably familiar with circadian rhythms. These are biological rhythms that play out over about 24 hours and are informed by the Earth?s rotation around the Sun. These form the broad structure of our individual days; the most obvious example of a circadian rhythm is the sleep-wake cycle, where we are alert and awake part of the day, and then move toward drowsiness and eventually sleep later in the day.

But circadian rhythms have lesser known cousins that can help us optimize our internal body clocks for maximum efficiency and well being. These are ultradian rhythms, or rhythms that play out in increments shorter than a day.

Examples include everything from heartbeat to digestion to the varying stages we go through during sleep.

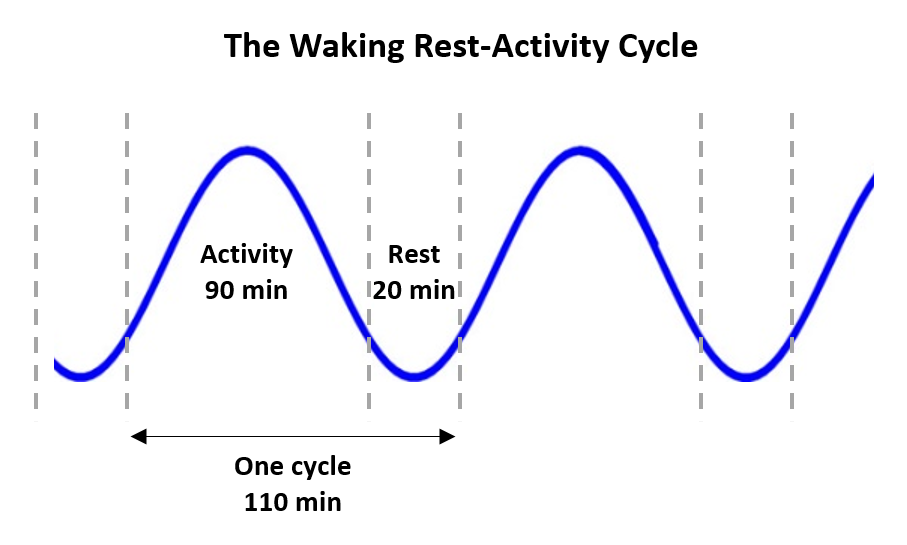

For productivity, we are concerned with the specific ultradian rhythm known as the Basic Rest-Activity Cycle (BRAC). This is a rhythm that plays out in 80?120 minute cycles non-stop, day and night. It is most detectable during sleep, when we move from non-REM sleep to REM sleep and back, over and over again throughout the night.

But it is also present in subtler forms throughout the day. To differentiate it from its nighttime twin, I?ll call this the waking rest-activity cycle ? and this is the focus of this article.

Note: There is also a class of rhythms known as infradian rhythms that last more than a day. Think of these as seasonal rhythms. For example: tides, menstruation, and breeding patterns. The hierarchy looks like this: infradian ? circadian ? ultradian.

![]()

BRAC and the Waking Rest-Activity Cycle

BRAC was first suggested in 1960 by physiologist Nathaniel Kleitman and his research assistant Eugene Aserinsky, both widely regarded as pioneers in the field of sleep research.

They used an early version of an electroencephalogram machine (or EEG) to study electrical currents of their subjects? brains while they slept. What they discovered was the various stages of sleep, now known broadly as non-REM and REM sleep. They later demonstrated that a similar ?rest-activity? cycle occurs more subtly while we are awake.

The premise is that our bodies go through alternating periods of rest and activity, and that each full rest-activity cycle lasts between 80?120 minutes. For example, in sleep we average 90 minutes of rest (non-REM sleep) and 20 minutes of activity (REM sleep) ? creating one full cycle totaling 110 minutes.

During wakefulness, this is flipped on its head: when correctly attuned to our biological rhythms, we experience 90 minutes of activity followed by 20 minutes of rest, cycled over and over throughout the day.

The problem arises when we ignore these rhythms and try to maintain constant activity throughout the day, failing to heed our regular need for a break.

Our goal is to make the most of those 90 minutes of activity by making the most out of those 20 minutes of rest.

![]()

The Waking Rest-Activity Cycle: A Background

The 20-Minute Break

The best resource I have found on how to utilize our waking rest-activity cycles is called The 20-Minute Break by Ernest Rossi, Ph.D. Rossi?s interest in the rest-activity cycle was born from his experience as an assistant to psychologist Milton Erickson, fabled for his unconventional approach to psychotherapy, which often involved hypnosis and other trance-like states.

Before either of them had learned about the waking rest-activity cycle, Rossi noticed that Erickson would naturally guide his patients through a session lasting roughly 90?120 minutes. During the last 20 minutes or so, the patient would begin to fade out mentally, and that is when Erickson would facilitate hypnotic trance.

Later, when Rossi first encountered literature about the Basic Rest-Activity Cycle, he put two and two together. He realized that by reviewing these cycles systematically, he could not only achieve better results in psychotherapy, but also create an accessible framework for individuals to experience more fruitful lives.

He calls his framework the Ultradian Healing Response.

The Ultradian Healing Response

The Ultradian Healing Response is just a fancy name for identifying when you need to rest during the day, and then making sure you get that rest. And to be clear, this doesn?t necessarily mean you need to take a nap (although if you need to nap, and have the ability to, that?s OK from time to time). It just means that you need to take a break from your work, and allow your mind to do its own thing.

I?ll go ahead and call this rest period the healing break.

Rossi says that during an adequate healing break:

?the mind-body resynchronizes its many rhythms and systems. Oxidative waste products and free radical molecules that have built up in the tissues during preceding periods of high performance and stress are cleared out of the cells. The stores of messenger molecules so vital to mind-body communication are replenished, and energy reserves are restored.

Psychologically, your mind works to make sense of and integrate the day?s experiences. Past experiences, feelings, and events are synthesized into a coherent stress-free whole, creating new levels of meaning and understanding.?

Sounds similar to what they say about sleep, doesn?t it?

Anatomy of the Waking Rest-Activity Cycle

Rossi simplifies things, and breaks the waking rest-activity cycle into 90 minutes of activity and 20 minutes of rest, making a full cycle last 110 minutes. Everybody is different, however, so one full cycle for you could last anywhere from 80?120 minutes.

Rossi does not provide a methodical approach to measuring how long your own particular cycle lasts. His approach to determining when you need to take a break is to pay attention to your body?s signals, and then to take a break when you need to ? using the 90/20 principle as a rough guide. His book focuses more on how to recognize these signals and on how to make the most out of your break.

While the information the book does provide is fantastic, I feel there?s a missing piece for a couple of reasons. One, the analytically minded among us need more than a rough guide; we want to know the details of our own specific cycles. Two, some may find it difficult to implement a 90/20 process when their current ?uninformed? patterns are all over the place ? with breaks sometimes as far apart as 3 hours and at other times as close as every 20 minutes.

For these reasons, I developed my own system for working up to a 110-minute cycle, and then winnowing in on my own particular metrics.

![]()

Putting it into Practice

Working up to a 90-Minute Work Session

The first step is to get a timer. I use the paid service Focus@Will, which plays specialized music using brainwave entrainment to help boost performance. Interestingly, it works on a similar 90-minute time frame per session, making it synergize perfectly with the activity component of the waking rest-activity cycle.

However, you can also adjust the app?s timer anywhere from 1 minute to 4 hours, meaning you can incrementally work up to an uninterrupted 90-minute work session.

Of course you can also use a simple, free online countdown timer. There are numerous browser extensions or you can use your phone.

The next step is to use a version of the Pomodoro Technique to gradually build yourself up to 90 uninterrupted minutes of work. The Pomodoro Technique consists of 25 uninterrupted minutes of work followed by a 5 minute break, with the entire cycle repeated four times before taking a 15?30 minute break after the fourth work session.

In our case, we will be doing three rounds of Pomodoro instead of four, and after the third round, we will take a 20-minute healing break la Rossi?s Ultradian Healing Response.

Pomodoro means tomato in Italian, and the technique is named after this cute tomato timer.

Pomodoro means tomato in Italian, and the technique is named after this cute tomato timer.

So set two timers, one for 25 minutes (work) and one for 5 minutes (break) and get to work.

After three sessions, take a 20-minute healing break, avoiding all mentally or physically demanding tasks. You can use another timer here too, but you don?t have to. You should be able to roughly gauge when 20 minutes are up, and/or when you feel you?ve had an adequate rest.

Later, we will look at how to optimize your 20-minute healing break, but for now, we?re just getting a feel for the pattern and building ourselves up to a full 90-minute session.

Nevertheless, you will see that this largely mimics the pattern of the waking rest-activity cycle, with two bonus 5-minute breaks built in (25+5+25+5+25=85 minutes of work, followed by your 20-minute healing break).

When you can do this two or three times per day for two to three days in a row, you can start to extend your work sessions.

After a few successful days of this, set two new timers, one for 45 minutes and one for 5 minutes. Work for 45 minutes straight, and follow it up with a 5-minute break. Do one more 45-minute session, and then take your 20-minute healing break.

Finally, after a few days, you can build up to 90 minutes of uninterrupted work, and then, of course, your 20-minute healing break.

Important: Throughout this entire experience, take notes about how you feel before, during, and after your work sessions and before, during, and after your healing break. Ask yourself these questions:

- At the end of your typical 90-minute work session, how do you feel? Do you feel like you could keep chugging along without burning out? Or did you run out of steam 10 minutes ago? Or maybe it feels like just the right amount of time?

- At the end of your typical 20-minute break, how do you feel? Do you feel like you need another 5 minutes before you?re ready to work? Or do you feel like you were ready 5 minutes ago? Or perhaps 20 minutes is just the right length?

How to Get the Most out of Your 20-Minute Break

Now that you built yourself up to the full 110 minute cycle, it is time to focus on optimizing how you spend your healing break. This is where Rossi?s book really excels. He discusses how to ease into the break, what to do during the break, how to apply hacks during the break to create changes in other areas of your life, and much more. The following is a basic checklist that I?ve synthesized and interpreted from the material:

- A short break is better than no break, so even if you take only 5 minutes to chat with a coworker, that is better than nothing.

- Try to avoid anything taxing, including reading and watching videos. If reading is truly the only thing that helps you relax, then go for it.

- This is not meant to be nap time. Naps activate the sleep version of the rest-activity cycle, which works differently than the waking rest-activity cycle. If you are so fatigued that you need a nap, and a nap is available to you, then by all means take a nap. Jump back into the waking rest-activity cycle when you are ready.

- Walking is fine if you work in a sedentary job, but find a route that is relatively free from loud distractions. Otherwise find a quiet place to sit or lie down, or remain at your desk if that is the only option.

- If you are sitting, close your eyes and listen to your breath and sense your pulse. If you are walking, listen to your breath and sense your pulse but pay attention to where you are walking (you don?t want to get hit by a car). Ease into these biological rhythms.

- This may feel like the beginning of a meditation, but that?s not what we are after. Here, you can allow your mind to go pretty much wherever it wants. Daydreaming and fantasizing are perfectly fine, but try to think comforting or restful thoughts. Feel free to work though any real-world challenges, but try not to get caught up in any negative emotions that may arise as a result.

- Each person has their own baseline cycle duration, but this can be altered by extenuating circumstances. If for some reason you work through your healing break, that doesn?t mean you have to wait another 90 minutes before you can take your break again. Take a break whenever you can, and then perform a shorter work session the next time. Your body is adaptable and can return to baseline if you let it.

Rossi goes on to describe more advanced ways to hack the hypnotic state brought about by the healing break, including tactics like cognitive reframing to help you transform negative experiences, and entrainment to help you sync your internal rhythms with external stimuli (e.g. overcoming jet lag).

I would highly recommend Rossi?s book, The 20-Minute Break for a more in-depth exploration of these topics.

Remember: Continue to take notes about what you experience during your healing break.

Identifying your Individual Patterns

Now that you have built yourself up to 90 minutes of uninterrupted work, and have experienced the 20-minute healing break, you can start to determine your optimal cycle lengths.

Maybe you run out of gas after 85 minutes, instead of 90. Maybe 15 minutes of rejuvenation is enough for you, and an additional 5 minutes of rest would be counterproductive.

Based on your data, you can tweak the duration of the 90-minute work session, the 20-minute healing break, or both. Try different combinations and continue to test and learn.

Meanwhile, try to internalize your experiences so you can eventually do away with the timer altogether. Ideally you will reach a point where you have become more familiar with your body?s signals, and can recognize when you need to take a break and when you feel refreshed enough to return to work.

It?s not just an exercise in productivity, it?s also an exercise in getting to know yourself better.

Final Thoughts

What I love about the concept of the waking rest-activity cycle is that it encompasses multiple areas of self-optimization. Not only is it a great tool for time-management and productivity, but it also offers a great foray into hypnotic and subconscious states.

Have a play around with it, and see what you learn. Let me know in the comments how it works out for you.

![]()

References

- The 20-Minute Break by Ernest Lawrence Rossi, Ph.D.

- Chronobiology by Bruno Dubuc at TheBrain.McGill.ca

- Basic Rest-Activity Cycle at Wikipedia

- Kleitman, Father of Sleep Research at The University of Chicago Chronicle

- The Pomodoro Technique by Cirillo Company at CirilloCompany.de