A new startup is catering to people who want more privacy?but that means giving up a chance to find relatives

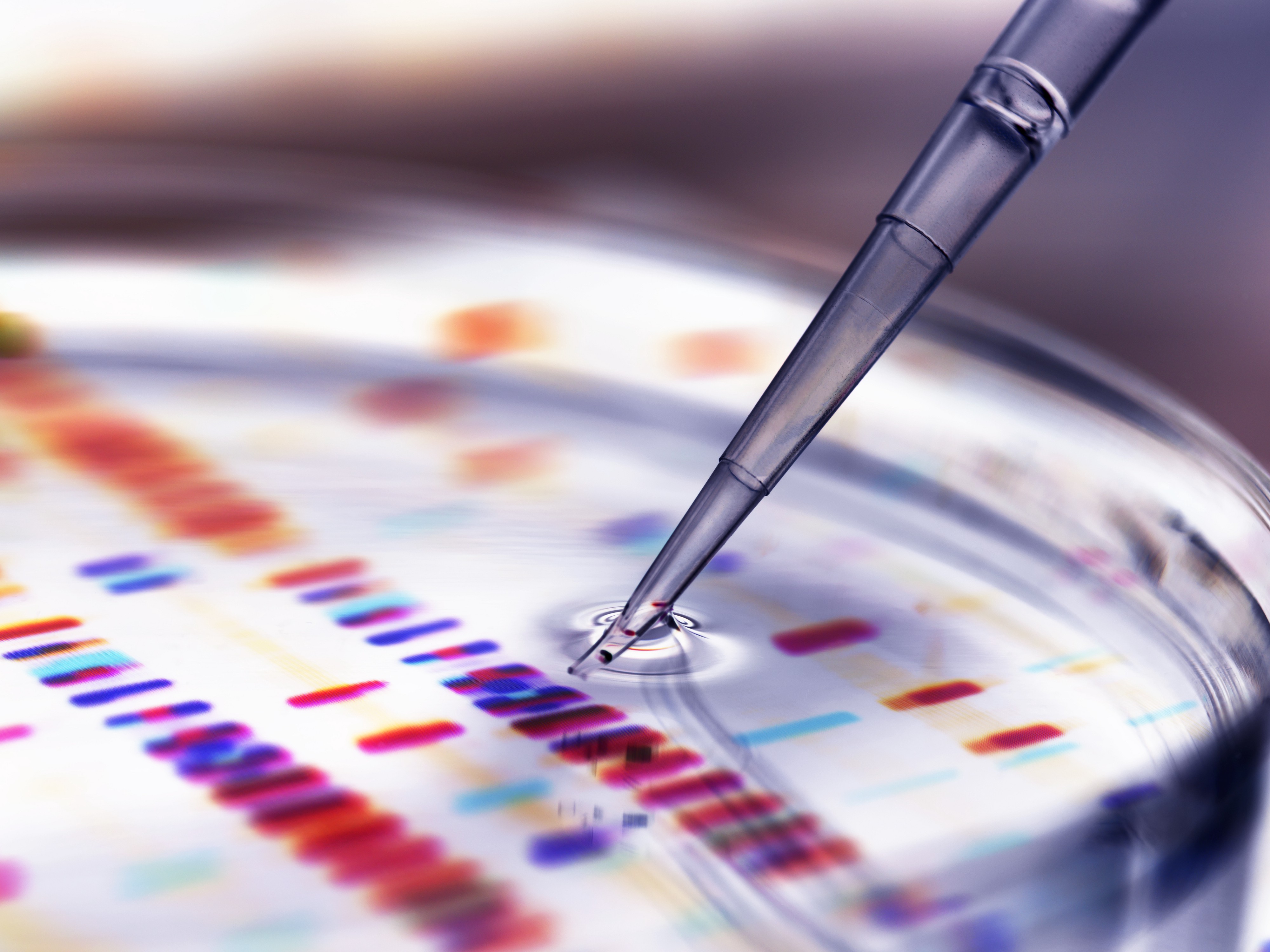

Photo: Andrew Brookes/Cultura/Getty

Photo: Andrew Brookes/Cultura/Getty

Brianne Kirkpatrick interacts with plenty of people concerned about privacy. One time, when the licensed genetic counselor was helping a client look over potential relatives based on DNA matches in the ancestry website FamilyTree.com, she found one with an unusual name: ?Not Saying.?

Brianne Kirkpatrick interacts with plenty of people concerned about privacy. One time, when the licensed genetic counselor was helping a client look over potential relatives based on DNA matches in the ancestry website FamilyTree.com, she found one with an unusual name: ?Not Saying.?

In mid-September, the startup Nebula Genomics announced it would be offering anonymous gene sequencing, which allows consumers to get their DNA tested without ever personally identifying themselves. The company is capitalizing on growing consumer distrust of genetic testing companies and fears that the information people obtain about their disease risk might be used against them. Consumers buying anonymous genetic testing would, like other genetic testing consumers, likely be using the product to identify genetic markers of disease risk and ancestry ? only without linking their genetic information to their identifying information. (Nebula is co-founded by Harvard geneticist George Church, who recently apologized for associations with Jeffrey Epstein.)

?People are beginning to care a lot more about what happens with their data and the services that they use, and they want to have transparency.?

?I understand why it would be attractive to a consumer because of the promise of anonymity,? Kirkpatrick says. But it?s not clear that anonymous testing will give most consumers what they really want, and critics fear that the potential to improve human health is lost in the conversation about consumer distrust.

Of all the reasons people choose to have their DNA sequenced, the top reason is to learn where they?re from. ?Ancestry testing is the most attractive direct-to-consumer product by far,? says Robert C. Green, a medical geneticist and professor at Harvard University who co-authored a study showing 74% of people who use personal genetic testing were ?very interested? in ancestry. (Green receives compensation for advising several competitors of Nebula.)

Of all the reasons people choose to have their DNA sequenced, the top reason is to learn where they?re from. ?Ancestry testing is the most attractive direct-to-consumer product by far,? says Robert C. Green, a medical geneticist and professor at Harvard University who co-authored a study showing 74% of people who use personal genetic testing were ?very interested? in ancestry. (Green receives compensation for advising several competitors of Nebula.)

Uploading genetic data into a genealogy website like Ancestry.com requires linking the data people get about their background to identifying information. This is how people are able to find and connect with family members and how police departments have identified culprits of crimes.

Although people may be drawn to genetic testing by an interest in their heritage, they often become interested in the health applications as they learn more, Green says. Nearly as many consumers in his study were interested in understanding their disease risk as they were in learning about their forebears.

Ancestry.com says it does not share users? information without permission, and medical information is theoretically secure. However, news of data breaches may not reassure people that the data they elect to keep private will remain so.

Many of the people who use direct-to-consumer gene testing also opt in to having their genome included in large databases, often called DNA biobanks. And while this data is usually de-identified, consumers have little faith in the industry?s ability to preserve their anonymity: According to a 2019 public survey on factors influencing a person?s decision to donate DNA and medical information, only 13% of respondents said they trusted company researchers.

?DNA itself is identifiable to individuals. Every hurdle that we can think of putting in place to protect someone?s privacy, there?s probably a way around that hurdle.?

Stories about cross-referencing personal and crime scene DNA databases to identify the Golden State Killer and other criminals have also spotlit the possibility that testing your DNA could implicate relatives. And despite the existence of some legal protections, documented instances of genetic discrimination by insurance companies and schools have caused hesitation in linking identity to genetic information.

In its own market research, Nebula has found privacy to be one of the main concerns deterring people from purchasing genetic tests. ?People are beginning to care a lot more about what happens with their data and the services that they use, and they want to have transparency,? says Jake Cacciapaglia, who leads business development at the company. ?That still seems to be the highest resonating reason for why [customers] are purchasing us versus other alternatives on the market.?

Nebula offers a higher level of anonymity to consumers by allowing them to pay with cryptocurrency or use post office boxes that obscure their physical addresses.

Additionally, the company?s model for sharing data with other companies hinges on the use of split decryption keys?digital codewords of sorts?one of which is given to the consumer. Much like the way some missiles require two keys turned by two people to launch, Nebula requires both parts of the key to be engaged for consumers? data to be shared.

However, this level of anonymity means the most popular reasons for purchasing genetic testing ? finding relatives and getting health information that is then shared with medical providers ? are not an option for most of Nebula?s customers.

However, this level of anonymity means the most popular reasons for purchasing genetic testing ? finding relatives and getting health information that is then shared with medical providers ? are not an option for most of Nebula?s customers.

Kirkpatrick empathizes with the desire for anonymity but says she isn?t convinced that any genetic testing company can truly offer it. ?DNA itself is identifiable to individuals,? she says. ?Every hurdle that we can think of putting in place to protect someone?s privacy, there?s probably a way around that hurdle.?

Although genetic testing in clinical settings is generally reviewed in consultation with a genetic counselor, most direct-to-consumer testing is not ? and comes with a warning advising users not to base health care or medical decisions on its results. Some Nebula users who want their genome interpreted without having the findings enter their medical records will upload their data to websites like Promethease, which draws on the genetics literature to develop personal DNA reports based on users? DNA sequence files. This is not always a frustration-free experience; several Reddit commenters confirmed Green?s assessment of the site as often yielding ?results that are contradictory or confusing.?

While Green says he respects privacy concerns, he doesn?t think those concerns should be the focus of the dialogue about genetic testing. In his opinion, the current narrative about the privacy problems of genomics has overshadowed its health benefits.

?What?s being lost in the dialogue is the potential health value of the genome and the fact that in order to realize that value, we?re going to have to bring genomics into the health care system,? he says.