Decoding the obscure language of iconography

Photo by Juan Di Nella on Unsplash

Photo by Juan Di Nella on Unsplash

The symbolic language of art is a language of intrigue and meaning.

Did you know that a lily means purity, or an ostrich egg signifies virginity? (More of that later).

One art historian, Erwin Panofsky, likened the language of artistic symbols to that of gestures between people. He imagined walking along the street and being greeted by an acquaintance who lifts his hat in friendliness:

?This form of salute is peculiar to the Western world and is a residue of medieval chivalry: armed men used to remove their helmets to make clear their peaceful intentions and their confidence in the peaceful intentions of others.?[1]

We don?t lift our hats anymore, probably because we don?t wear hats or else we don?t want to mess our hair up. The point is that signs and symbols communicate ideas, and those symbols have a wonderful history.

For me, one of the great pleasures of visiting an art gallery is in exploring the possible meanings of the works on display. After all, every picture tells a story, yet for many visitors the language of art is a mystery.

Woodcut print from a 1618 edition of Cesare Ripa?s ?Iconologia?. Shared under Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license.

Woodcut print from a 1618 edition of Cesare Ripa?s ?Iconologia?. Shared under Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license.

For centuries, artists have drawn on a rich collection of stories, from ancient Greek and Roman myths to the stories told in the Old and New Testaments. As the centuries passed, a language of symbols developed so that artists could tell these stories with deeper and more intricate emphasis.

People still read the classics of Greek and Roman literature, and thanks to blockbuster films, the names of ancient gods and characters such as Jupiter, Achilles and Helen are still alive in our imaginations. The Bible too ? upon which so much of Western art is based ? continues to be read. Yet for the understanding of art, it is useful to know not just the stories but also the ?rules? that artists followed (and sometimes broke) in order to depict these stories.

It also makes a trip to an art gallery far more enjoyable.

Legends and Lore

As a student of art history, one of my biggest delights was to come into contact with some of the more esoteric sources of pictorial conventions. One such text, for instance, which had a huge influence on Christian symbolism, is the Golden Legend.

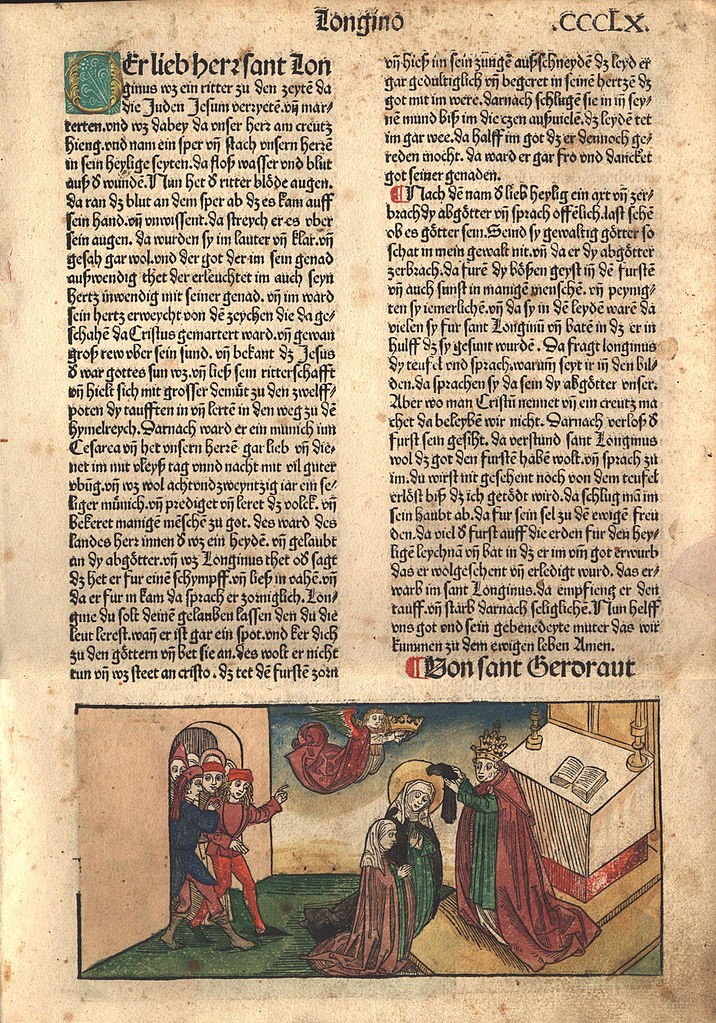

Folio Page from ?The Golden Legend? by Jacobus de Varagine (1228?1298). Printed by Anton Koberger, 1488. Shared under CC BY-SA 3.0

Folio Page from ?The Golden Legend? by Jacobus de Varagine (1228?1298). Printed by Anton Koberger, 1488. Shared under CC BY-SA 3.0

Written around 1275 by a Dominican friar called Jacobus de Varagine, the Golden Legend is a compilation of the lives of the saints and legends of the Virgin, as well as other stories relating to the Christian calendar.

Since the Golden Legend is a collection of traditional folklore about the saints; you won?t find these stories in the Bible. The tales of martyrdom and heroism were widely read in medieval Europe, and as such entered the vocabulary of artists and the conventions of their work.

To give an example, if you see a figure in a painting holding a palm leaf, then they are almost certainly a martyred Christian saint whose story is told in the Golden Legend.

St. Lucy, by Francesco Zaganelli (c. 1475?1532). Tempera and gold on wood. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Theodore M. Davis Collection, Bequest of Theodore M. Davis, 1915. Photographed at the Metropolitan by Richard Stracke, shared under Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license.

St. Lucy, by Francesco Zaganelli (c. 1475?1532). Tempera and gold on wood. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Theodore M. Davis Collection, Bequest of Theodore M. Davis, 1915. Photographed at the Metropolitan by Richard Stracke, shared under Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license.

Here is a painting of St. Lucy by the Italian painter Francesco Zaganelli. The green palm leaf she is holding in her left hand tells us straight away that she is saint who came to her death because of persecution.

The association of palm leaves with saintliness comes from the feast of Palm Sunday, a celebration in Christianity commemorating Jesus? entry into Jerusalem when palm branches were placed along his path.

The symbolism of the palm branch in fact stretches back to the ancient world, where it was a symbol of victory and peace. A victorious athlete competing in ancient Greece, for instance, was awarded a palm as a symbolic prize. The palm also has a place in the Muslim tradition where, as a symbol of peace, it is associated with heavenly Paradise.

In the Western artistic tradition, individual Christian saints such as Lucy and Catherine can be further distinguished by objects they tend to be holding or stood beside. These items are known as ?attributes?.

Let?s examine the case of St Lucy in a bit more detail, since she offers a good example of how pictorial traditions actually help embroider stories.

St Lucy lived in Italy, and died around 304 during a widespread persecution of Christians under the Roman emperor Diocletian. She was a real historical figure, yet her depictions in art tend to focus on legends.

As the above image shows, Lucy holds a palm leaf to indicate her martyrdom. Sometimes she is shown at the moment of her death, which was said to have occurred by a knife to the throat.

Saint Lucy, by Francesco del Cossa (c. 1430 ? c. 1477). Source Wikimedia Commons

Saint Lucy, by Francesco del Cossa (c. 1430 ? c. 1477). Source Wikimedia Commons

Not all depictions of Lucy are quite so gruesome, however. Since her name comes from the Latin lux, meaning ?light?, she is sometimes shown holding a candle or oil lamp. Most common of all, she is shown holding a pair of eyes, sometimes held between her fingers and sometimes resting on a plate in her hand or else sprouting from a stalk. Originally the eyes were given to her simply as an allusion to her name, and developed as a convention since she became associated with the protection of people?s eyesight. Legends were later developed to give additional meaning to the eyes: in one story she was said to have had her eyes gouged out by a tyrant; in another she plucked them out herself to subdue an admirer who would not stop praising them.

Mary?s Flora

As with all symbols in art, the rules are never hard and fast. A palm leaf indicates a martyred saint, but sometimes a palm leaf is used as specific attribute of an individual saint too: in depictions of John the Evangelist, who is the presumed author of the fourth gospel, he is sometimes shown holding a palm leaf. This relates the Virgin Mary on her deathbed, at which moment she is said to have handed him her palm. Again, this is an apocryphal story ? in other words, it doesn?t appear in the Bible.

?The Death of the Virgin? by Andrea Mantegna (c.1431?1506). Source

?The Death of the Virgin? by Andrea Mantegna (c.1431?1506). Source

Look at this painting of the Death of the Virgin by Andrea Mantegna. We can now identify the figure on the left in the green robe as John the Evangelist, since he is clearly holding a palm leaf. With a bit more detective work, we could probably identify all the other figures surrounding the dying Mary. One thing is for certain: they are all divine or sanctified people, because of the halos hovering above their heads.

As well as a palm leaf, another item of flora that is often seen in association with the Virgin Mary art is a lily flower, the presence of which indicates her purity.

One theme of the Virgin?s life in which a lily is nearly always present is the Annunciation, as painted by Leonardo da Vinci, for example. The Annunciation was the moment that the angel Gabriel appeared to Mary and announced she would conceive and bear a son.

?Annunciation? by Leonardo da Vinci (1452?1519). Shared under CC BY-SA 4.0

?Annunciation? by Leonardo da Vinci (1452?1519). Shared under CC BY-SA 4.0

Sometimes the lily is in a vase; at other times the angel is shown carrying is, as in Leonardo?s painting. Why a lily? Well, since the event occurred nine months before the Nativity, the events of the Annunciation were calculated to have occurred on 25 March. The spring setting gave rise to the motif of the flower, which later refined to a lily. Leonardo decided to give his painting an all-over spring feel, with a lush carpet of flowers beneath Gabriel?s feet.

The Virgin Mary became deeply revered during the late medieval and Renaissance periods. For the Christian Church, the Virgin Mary emerged as the Purissima or ?most pure? of figures. It?s for this reason that she appears often as the subject of art, sometimes through episodes of her life, as we have seen, and sometimes as the mother figure of Christ.

Adam?s Apple

In Western art, paintings of the Virgin and Child were extremely popular. They are so numerous that it is impossible to find a single set of conventions to which they all accord. Here is just one detail which is always worth looking out for.

? Virgin and Child Surrounded by Angels? by Quentin Massys (1466?1530). Source Wiki Commons.

? Virgin and Child Surrounded by Angels? by Quentin Massys (1466?1530). Source Wiki Commons.

The symbol of an apple was sometimes taken up by painters when depicting the infant Christ, for instance, in this painting by Quentin Matsys, which shows the Christ Child held by his mother. Now, if you look closely to the left side of the painting, at the bottom of the column is an apple.

Why an apple? In fact, apples are one of the most prevalent fruit in all of Western art, and have several meanings depending on the context. Probably most well-known of all apples is the one that Eve offered Adam in the Garden of Eden.

According to the Book of Genesis, Adam and Eve were the first humans, created by God in his own image. God placed them in the Garden of Eden, an earthly paradise where the only rule was not to eat the fruit from the Tree of Knowledge. Unfortunately, a serpent tempted Eve to eat some of the ?forbidden fruit?, and when she also gave some to Adam, they both recognized their nakedness and covered themselves with a fig leaf. This symbolic act was in recognition of their shame at disobeying God?s orders.

?The Fall of Man? by Peter Paul Rubens (1577?1640). Source Wiki Commons

?The Fall of Man? by Peter Paul Rubens (1577?1640). Source Wiki Commons

In paintings of this scene, the forbidden fruit is typically shown as an apple, sometimes proffered by the snake hanging down from a tree, and sometimes held in Eve?s hand as she passes it to Adam.

So what about Christ?s apple? The purpose of showing the Christ child with an apple is to connect Him to the story of Adam and Eve: if Adam and Eve were responsible for the ?fall? of humankind, then Christ is suggested as being the redeemer. The symbol of an apple is a way of uniting the stories into a grander narrative, reaching back in time and stretching into the future.

Ostrich Eggs

The history of art is replete with symbols both commonplace and cryptic. To end this cursory look at symbols in art, I thought I?d share one of the more obscure reverences in the tradition, and one of my favorites too.

?San Zaccaria Altarpiece? (1505) by Giovanni Bellini (c.1430?1516). Source Wikiart

?San Zaccaria Altarpiece? (1505) by Giovanni Bellini (c.1430?1516). Source Wikiart

Take this painting by Giovanni Bellini. It shows Mary and Christ surrounded by fours saints, positioned symmetrically about the throne. The overall style of painting is known as a sacra conversazione, a tradition in Christian painting where several saints are gathered together around the Virgin.

Among the riches of this painting, one fascinating detail is at the very top of the picture, so easy to miss: an ostrich egg hanging from a chord.

What is an ostrich egg doing hanging in mid-air like that? Well, how much do you know about incubation habits of ostriches?

It is now known that ostriches lay their eggs in communal nests, which consist of little more than a pit scraped into the ground. The eggs are incubated by the females in the day and by the males at night.

However, in medieval times, the ostrich ? a much admired bird at the time ? was commonly believed to bury its eggs in sand and allow the heat of the sun to carry out the incubation. On account of the young emerging without parental involvement, it was thought that the ostrich egg was an ideal symbol of the virginity of Mary ? a theologically tricky concept for which parallels in nature were sought.

So the ostrich egg was a symbol Mary?s virginity, which is why it has pride of place at the very top of this painting.

Next time you?re at a dinner party, see if you can squeeze that one into the conversation.

Would you like to get?

A free guide to the Essential Styles in Western Art History, plus updates and exclusive news about me and my writing? Download here.

Christopher P Jones is a writer and artist. He blogs about culture, art and life at his website.

If you want to know more about the San Zaccaria Altarpiece by Bellini, here?s a more detailed analysis:

How To Read Paintings: Bellini?s San Zaccaria Altarpiece

The decoding of a Venetian masterpiece

medium.com

Notes

[1] Panofsky, Erwin. ?Iconography and Iconology: An Introduction to the Study of Renaissance Art.? In Meaning in the Visual Arts: Papers in and on Art History. By Erwin Panofsky, 26?54. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1955.