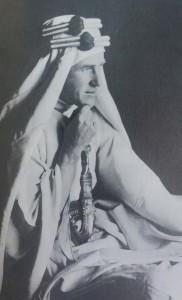

T.E. Lawrence

T.E. Lawrence

As I was reading through T.E. Lawrence?s military memoir Seven Pillars of Wisdom, I asked myself, ?What are those seven pillars of wisdom anyway?? Nowhere in his account of the 1917 Arab Revolt does Lawrence ever mention seven pillars. What were they and what could they possibly mean?

My quest led me down a path of discovery, from the Bible to John Ruskin to Robert Graves, whose book The White Goddess is a source of New Age druid and bardic lore.

Seven Pillars of Wisdom is a detailed, factual account of Thomas Edward Lawrence?s stint as liaison officer between the British forces and the Arab resistance to the Ottoman Empire during the First World War. Arab officers rebelled against their Turkish commanders and declared open revolt against their crumbling empire. This ?Arab Revolt? was fought to win national independence for the Arab people from their provincial oppressors in Damascus.

Lawrence ? better known as Lawrence of Arabia ? fought alongside them, coordinating a manoeuvre war with Arab commanders as he played a role in rallying tribes of nomads to fight as a united nation against the Turkish empire.

In his memoir, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Lawrence?s poetic observations of the harsh, magnificent landscape accompany an account of the day-to-day marches across the land to outflank and outmanoeuvre the Turks. He instructs rebels to lay charges and detonate explosive gel under train tracks that ferry supplies to Turkish garrisons and towns. Moments of still peace and contemplation of strategy accompany moments of sudden violence, all described with the highest literary sensibility.

Seven Pillars of Wisdom reads like an epic novel in its length and in the florid description of Lawrence?s extensive journeys. Some of its accounts are boastful and perhaps outright fabricated, as Suleiman Mousa claims in T.E. Lawrence: An Arab View. But the legacy of the Arab Revolt finds echoes in the wars for independence that continue to wage on in the Middle East today. This is especially true of Syria, where the defections of 1916 echoed the defections in 2011, and where the lines drawn by the Sykes-Picot Agreement still define national borders. All this testifies to the continued relevance of Seven Pillars of Wisdom for the modern world.

Photo by RAKAN ALREQABI on Unsplash

Photo by RAKAN ALREQABI on Unsplash

But whence that mysterious title? What, indeed, are wisdom?s seven pillars?

The most well-known reference to the seven pillars of Wisdom can be found in the Bible: ?Wisdom has built her house, / she has hewn her seven pillars? (Proverbs 9.1).

Wisdom is personified as a woman who has prepared a great feast. Only the wise are invited to this banquet; the foolish are unworthy.

Although I could not find any further explicit references to seven ?pillars of wisdom? in the Bible, the Book of James lists seven qualities of pure wisdom that can stand for these:

But the wisdom that is from above is first pure, then peaceable, gentle, and easy to be entreated, full of mercy and good fruits, without partiality and without hypocrisy. (James 3:17)

Biblical wisdom is not the only kind of wisdom Lawrence finds on his journey. Jewels of profundity are laced throughout the Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Lawrence, though alien, becomes immersed in the Arab viewpoint as he experiences the war alongside them, learning from the wisdom of Bedouin and Howeitat elders. One such kernel is striking:

?Why are the Westerners always wanting all?? provokingly said Auda. ?Behind our few stars we can see God, who is not behind your millions. [?] If the end of wisdom is to add star to star our foolishness is pleasing.? (289)

Auda mocks Lawrence and his Western compatriots for the impotence of their rationalized wisdom. Read in this light, the title of Lawrence?s book could be read as a dig at the Western mindset, or even a subtle critique of imperialism.

However, this is not the whole story behind why Lawrence called his memoir Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

Wikipedia explains that Seven Pillars of Wisdom was the title for a previous book Lawrence had been planning to publish before the war broke out. It was to be a scholarly work about the seven greatest cities of the Middle East: Cairo, Smyrna, Constantinople, Beirut, Aleppo, Damascus, and Medina.

The formula of the title was itself likely inspired by John Ruskin?s treatise Seven Lamps of Architecture, which Lawrence had previously read. In Seven Lamps of Architecture, Ruskin describes the Lamp of Truth as the ?only one of which there are no degrees, but breaks and rents continually, that pillar of the earth, yet a cloudy pillar? (qtd. in Jeffrey Meyers, ?The Revisions of Seven Pillars of Wisdom,? 1066).

This early manuscript, ?a youthful indiscretion-book? (qtd. in Meyers 1066) never saw the light of publication. Lawrence destroyed it. To worsen matters, he would also lose his first manuscript of Seven Pillars of Wisdom in 1919, at Reading train station. Just in time for Christmas. It has never been recovered and would have been 250,000 words in length.

In the memoir that eventually saw publication ? painfully rewritten by a shellshocked Lawrence overwhelmed by the demands of his own celebrity status as a war hero ? the author makes reference to these seven cities, in one way or another. Damascus, for instance, was the center of Turkish control over the Arab Middle East and one of the revolt?s main targets. Today, age-old Damascus is the capital of Syria. Owing to the new focus of his book, Lawrence skims over any further significance he may have attached to these seven cities.

Calling these seven cities the ?seven pillars of wisdom? comes across as an unconventional metaphor. So, why maintain that title after the book?s direction shifted from a geographical survey to a military memoir? Where is wisdom to be found in the rebellion of a people for independence?

To answer this question, we must turn to Robert Graves.

Graves was a renowned war poet, just as Lawrence was renowned a wartime writer. Furthermore, they corresponded with each other and had a working literary relationship. Graves wrote a review for Seven Pillars of Wisdom and edited the poem Lawrence wrote as the dedication to his memoir: ?To. S.A.? This poem may have been addressed to Selim Ahmad, a young Syrian boy. It is written in such a way that it could address the Arab nation as a whole:

I loved you, so I drew these tides of men into my hands

and wrote my will across the sky in stars

To earn you Freedom, the seven-pillared worthy house,

that your eyes might be shining for me (ln. 1?4)

Lawrence here modifies the Biblical allusion to Wisdom cited above. It is now Freedom who has ?a seven-pillared worthy house.? Freedom is preparing a feast. Those who are unworthy of Freedom are left out, but the worthy ones are invited in to dine. Lawrence could have titled his memoir Seven Pillars of Freedom if he?d been more literal-minded.

It is also suggested that wisdom is a kind of freedom. After all, you cannot be truly free without wisdom, since without wisdom you?re bonded to foolishness.

Although I am not certain how Robert Graves edited ?To S.A.,? I?d like to speculate that he may have left his own ideas upon it, either in the editing process or by influencing Lawrence in other ways. Since Lawrence was a bookish man as well as a soldier, he might have read Graves?s poetry and nonfiction himself, including his classic book on ancient druid and bardic lore, The White Goddess, which makes further allusion to the ?seven pillars of wisdom.?

Photo by Adrian Moran on Unsplash

Photo by Adrian Moran on Unsplash

Chapter 15 of The White Goddess is, in fact, entitled ?The Seven Pillars.? This is certainly suggestive of any influence Graves might have had on Lawrence, although any more specific connection between Seven Pillars of Wisdom and The White Goddess evades me presently.

In this chapter, Graves says that ?the seven pillars of Wisdom are identified by Hebrew mystics with the seven days of the Creation, with the seven days of the week? (259).

Of course, the number seven being a symbol of completeness can already be found in the verse from Proverbs. But Graves finds a further correlation, adding to the mystique of the ?seven pillars? motif.

The seven pillars correspond to the seven sacred trees of the Irish grove: ?birch, willow, holly, hazel, oak, apple and alder? (259). Each tree furthermore corresponds to a day of the week and a deity of the classical Graeco-Roman pantheon.

Alder corresponds to Saturn (Saturday), apple to Venus (Friday), oak to Jupiter (Thursday), willow to the Moon, or Circe (Monday), holly to Mars (Tuesday), birch to the Sun (Sunday). The seventh tree, hazel, corresponds to Mercury and its day falls in the middle of the week, on Wednesday.

Now, Wednesday in English is named after Odin (Woden), the Norse god of wisdom. This implies that his sacred tree, the ash, may be substituted for Mercury?s hazel. Not accidentally, Mercury is also a god of wisdom. Hence, if you imagine the seventh tree as being the most important, you could call the seven sacred trees ?the seven pillars of Wisdom? (a.k.a. ?the seven trees of Mercury/Odin?). If Irish trees were used to build Wisdom?s house, each pillar might have be fashioned from a different kind of wood.

Although speculating about patterns between the gods, the days of the week, the planets, the sacred trees, and the seven greatest cities of the Middle East might be straying into mysticism, what this investigation has demonstrated is that the ?seven pillars of wisdom? motif has a host of different connotations. Perhaps the seven pillars have as many different interpretations as there are mnemonics that attach significance to the number seven.

In the end, it appears that Lawrence was inspired to title his memoir Seven Pillars of Wisdom simultaneously as a Biblical allusion, a tribute to Ruskin, and an allusion to his poem, ?S.A.,? which was strongly influenced by his relationship to Graves. However, the phrase ?seven pillars of wisdom? is also a motif with much wider connotations in world culture.

To further suggest the relationship between Graves and Lawrence, there is a line in The White Goddess that could?ve served as an extension of Lawrence?s poem. It comes in the form of a Latin acronym built from the first letters of the names of each sacred Irish tree:

?Benignissime, Solo Tibi Cordis Devotionem Quotidianam Facio.? In English, this reads, ?Most Gracious One to Thee alone I make a daily devotion of my heart.? (260)

A line that Lawrence could well have spoken to his dear Selim, as a message to the Arab people.

Photo by Yunus klifa on Unsplash

Photo by Yunus klifa on Unsplash

If you enjoyed this story, you might enjoy my blog Archaeologies of the Weird.

Originally published at matthewrettino.com on February 6, 2016.