?Why does YouTube suck?? That?s the fourth most popular result on Google Search, after ?keep pausing?, ?keep signing me out?, and ?have ads.? Dumb as Google suggestions can be, it?s a surprisingly good question, and a telling sign of how people view the platform. What happened to the days of Gangnam Style and sneezing pandas? How did the internet?s greatest beacon for free speech, social change, and progress become the subject of ridicule, media controversy, and a symbol of corporate greed?

YouTube?s place on the internet

When you think of ?social media?, YouTube probably isn?t your first thought. Probably Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, or one of the other dynamic, mobile-friendly platforms comes to mind. By comparison, YouTube is a relatively static platform.

Every social media network needs users, with each user acting as a producer and/or consumer of content. On Facebook, nearly every user has an account that they use to interact with a close network of friends and family. Twitter hosts normal users alongside celebrities and companies, but using the platform as intended at least requires signing up for an account ? even if you?re not tweeting much yourself. YouTube, meanwhile, only really requires a special account if you want to upload your own content (even if some people stay signed in to their Google accounts.)

And yet, YouTube remains the largest social network. Even as Facebook boasts 20% more monthly active users, it gets only 85% the number of actual visits. Though YouTube may not reflect the changing tides of how we consume the internet ? only 62% of YouTube views come from mobile, where 96% of Facebook users use mobile ? what is does reflect is the interests of the internet as a whole. Even as interests have shifted in the past decade and a half since its founding, YouTube has remained the most accessible platform. This longevity and popularity makes YouTube the ideal candidate for analyzing the internet as a whole.

Humble Origins

YouTube may have quickly risen to stardom, but its beginnings are far from grand. Created by three former Paypal employees ? Steve Chen, Chad Hurley, and Jawed Karim ? the idea for a digital database of videos was sparked by their trouble finding videos about Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami and the Janet Jackson Super Bowl exposure incident. In February 2005, the ?YouTube.com? domain, trademark and logo were registered. A few months later, on April 23, 2005, the first video titled ?Me at the Zoo? was posted, featuring co-founder Jawed Karim in front of the elephant habitat at the San Diego Zoo. From there, it only took a few months before the website skyrocketed in content and popularity due to easy embedding to other sites and simple upload process (just click upload). In November 2005, YouTube secured private equity funding from Sequoia Capital, which allowed for better bandwidth and for the site to launch out of beta the following month.

YouTube circa 2005

YouTube circa 2005

Sequoia?s investment also served as a stepping stone for collaborations with other corporations ? and towards monetization from said collaboration. The first video to gain over a million views was a Nike commercial posted in September 2005. This served as a symbol of how later in later years, corporations take advantage of the accessibility of YouTube. Less than a year later, a clip of NBC?s ?Saturday Night Live? called ?Lazy Sunday? became popular on the platform, only for the network to demand a takedown for copyright infringement. In a shocking turn of events though, NBC later came back by announce an official partnership with YouTube, in hopes of boosting the network?s viewership and ratings via an official channel. This allowed the network to portray themselves in the light in which they wanted to be perceived, while catering to demand for their popular shows, such as ?The Office? and ?Saturday Night Live.? It was quickly becoming apparent that YouTube?s ease of use and open access meant that copyrighted content was massively at risk, creating a sort of ?make money with [YouTube] or none at all? mentality. Other companies, the majority of which were music companies such as Warner Music Group, also created agreements with YouTube, which furthered the YouTube dream of having high quality content and monetization on the site. This further cemented their legitimacy, triggering an avalanche of corporate deals with YouTube.

In October 2006, Google bought YouTube for $1.65 billion, less than two years after its initial launch. With the financial and technical backing, it seemed things were looking up for the online video revolution.

Monetization on YouTube

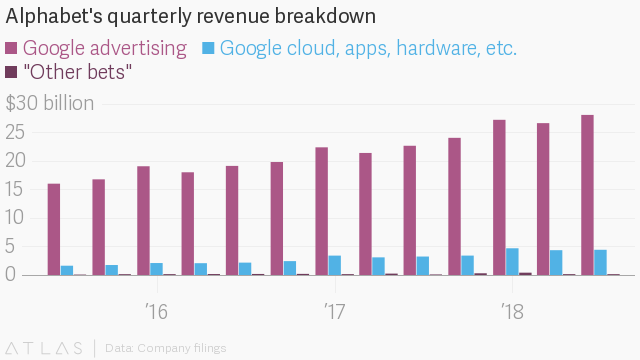

With its acquisition by Google, YouTube became another part of the tech giant?s portfolio ? and, by extension, their finances. It?s now that we should probably take a brief detour into Google?s finances.

Google, unlike Amazon, does actually turn a net profit each quarter. Alphabet, Google?s parent company, reported a net income of $30.7 billion last year on a revenue of $136.8 billion. In what should be no surprise to anyone, almost all of this is from a single source: advertising.

Google?s advertising platform is based on a single idea: the more information you can gather about someone, the more targeted and therefore more effective advertising can be. This allows Google to build an end-to-end pipeline for advertising: advertisers pay Google for advertisements, which can then be placed on their products and targeted using user data collected from the same products. An immediate corollary is that the more open a platform is, the more users that can and will want to join, and the more data that can be collected and used. All that?s left then is to build (free) products that people want to use, crunch some numbers, slap some ads on, and give the platform a name (or two) ? Google AdSense and Ads (formerly AdWords.) Of course, there?s a lot of infrastructure and management needed, but the core principle is remarkably simple.

Back to YouTube then. With its existing corporate partnerships, the potential for YouTube as an advertiser-friendly platform was clear. In May 2007, the ?YouTube Partner Program? launched. The program sought to close the gap between the original content posted by YouTube community and official partners of YouTube. Participants of the program, mid to large scale creators, were given the opportunity to monetize their uploads. Suddenly, an internet hobby could be transformed into a professional career, resulting in more frequent and higher quality videos to the site. Creators could quit their ?day jobs? and dedicate their time solely to YouTube. From then on, the hours of content being uploaded to YouTube every minute grew exponentially. Currently, 500 hours of video are uploaded every minute.

However, managing a YouTube channel is tough work, and transitioning a channel into a full-time career isn?t easy. In the desire to keep publishing high-quality content, creators often resorted to signing deals with larger umbrella corporations. This led to an upsurge of ?multi-channel networks? such as Machinma and Fullscreen, who sign contracts with channels to give supposedly give creators an easier time in gaining advertising revenue. This institutionalization and marketing arms race raised the bar for entry onto the platform, driving away smaller channels who found themselves unable or unwilling to compete. The Wild West days of YouTube were over.

YouTube circa 2012

YouTube circa 2012

Around October 2012, YouTube changed its recommendation algorithm (the part that displays videos on the home screen and side bar.) Instead of a ?view? on a video counting as a simple click, the algorithm began tracking watch time, or how long users stayed after clicking a given video. In essence, the algorithm recommend videos and channels based on how much total time people spent watching it. This change meant that shorter-form content, such as viral videos, animations, and comedy sketches fell out of favor, with lower effort but longer personality-driven content such as ?vlogs? and ?let?s plays? taking over. Vloggers like Casey Neistat and Dude Perfect, and Let?s Players like Pewdiepie and TheDiamondMinecart to hold top spots in YouTube?s trending page. With YouTube mandating ever higher requirements to reach Partner status, breaking into the YouTube space as a professional personality became even more difficult.

The Adpocalypse

In mid 2016, major companies, such as Johnson & Johnson and Coca-Cola, pulled their ads following a series of controversies surrounding what videos their ads were displayed on. Tensions had started brewing after their ads were shown before videos that contained anti-semeticis content, hate speech, and dark undertones. The final straw came when the world?s (at the time) most subscribed YouTuber PewDiePie came under fire for jokes about Hitler, Jews, and his use of the N-word. In response, YouTube updated their policies, resulting in mass demonetization of videos across the site ? even of videos that didn?t violate YouTube?s Terms of Service. These changes hit certain YouTubers particularly hard, including longtime creator Philip Defranco, whose posts about domestic and international news were considered ?controversial or sensitive.?

The damage only continued when in the beginning of 2018 popular YouTuber Logan Paul posted a video of himself in the infamous Japanese suicide forest. In the video, his crew finds and jokes about the body of someone who had died there. The video was up for over 24 hours, and was even towards the top of the YouTube trending page before Paul himself took the video down. YouTube finally responded 10 days later with what seemed like a slap on the wrist by temporarily revoking his monetization. Later, they pushed out an updated policy in which they attempted to define what kind of content was not suitable. Meanwhile, other channels, especially small ones focusing on body positivity, mental health, and the LGBTQ+ were demonetized.

Logan Paul

Logan Paul

Starting in mid 2017, the site again came under fire for hosting disturbing videos targeting children that portrayed popular children?s cartoon characters involved in gruesome, disturbing, or violent activity. The scandal has been termed ?Elsagate? due to the popular character from Frozen being one of the main characters portrayed. ?Elsagate? videos were also found to be using YouTube?s classification algorithms to appear more family-friendly by including tags and keywords such as ?education? and ?nursery rhymes.? Further suspicion arose due to the popularity and profitability of the videos due to their low effort content and frequent automatic ads. The controversy further grew to after the channels Toy Freaks and FamilyOfFive came under fire for their exploitative use and abuse of children in their videos. Though the channels were terminated in late 2018, the damage was done. YouTube?s role in child abuse was again brought into the limelight when in early 2019 creator MattsWhatItIs created a video exposing a mass of softcore pedophilic content on the site, causing companies to pull their advertisements from YouTube and another wave of demonetizations. Following a $170 million settlement with the FTC and fearing further potential legal prosecution under the Children?s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), YouTube announced plans to institute new content policies (namely that individual channels will need to identify their desired audience), triggering another wave of creator backlash and, of course, demonetizations.

The End of ?Broadcast Yourself?

The adpocalypse isn?t an isolated series of events though. Troubling as bigoted and disturbing content is, in a vacuum, YouTube would probably be able to dismiss it as the work of a few bad actors. However, the internet landscape has changed. The old view of the internet as a bastion of free speech, where discourse and discussion will lead to the spread of good ideas and content, has been challenged. The usage of the internet by powerful, malignant groups such as the far right and (domestic and foreign) terrorists, to spread their message has made it apparent that not all expression is good expression. Further, the use of major platforms such as Twitter by ISIS and Facebook with the Christchurch mosque killings has brought mainstream media attention to the darker side of these major sites. When your worst moments are on display for the world, it tends to cause people to question your values. It?s a lot easier to support free expression when what?s being put up aligns with your corporate message ? and, moreover, that of your shareholders and stock price.

At the end of the day, the changes that YouTube made that caused the adpocalypse were about their bottom line. Advertising is Google?s core product, and advertiser interests come first and foremost ? especially when those advertisers are using Google?s services to advertise on more than just YouTube. Even though their refusal to monetize certain content drives creators away ? and, in turn, users with marketable data ? they don?t care.

Google?s bet is that YouTube?s sheer size will keep it afloat. So far, they?ve been right. To understand why, we need to revisit YouTube?s finances. Though YouTube?s failure to turn a consistent profit might seem like a weakness that potential competitors could exploit, it?s actually representative of a wider issue with streaming monetization, and in turn, a strength for Google. On a technical and financial level, the high costs associated with the computing infrastructure and software development represent both a high initial barrier and continual operating costs for anyone looking to break into the video space. Combined this with the inherent difficulty of monetizing a video platforms and it?s difficult endeavor. Vine couldn?t make money, and TikTok survives largely off money from the CPC. Snapchat still hasn?t turned a profit. Even with their unique revenue model, including donations, subscriptions, and special rewards alongside the normal advertisements, Twitch?s profitability for Amazon is likely minimal. Though Netflix turns a profit, Hulu, Vessel, and even YouTube?s own Premium product (along with a host of others) have demonstrated that profitability isn?t as simple as introducing a subscription. However, unlike every company outside of Facebook and Amazon, Google can afford to lose money on their streaming services ? so long as it gives them valuable user data that they can integrate into the rest of their advertising suite. Further, like with their subscription-based counterparts, YouTube is betting that its users are flexible with their consumption habits ? especially if they don?t have to change them much. So long as they?re able to support the most popular creators, users will probably stick around, and any up-and-coming creators will simply be forced to go where the users are ? even if it makes monetization harder. So far, it?s working: creators have simply been forced to deal with demonetization on their own and find alternative revenue streams, usually in the form of other sponsored content or native ads. That pushes the bar for being successful on YouTube even higher, since making money on the platform isn?t as simple as just clicking a button, in turn ostracizing more potential creators.

What we?re seeing here is a consolidation of power. New, viral YouTube channels are almost nonexistent in the US. There?s no ZomboCom 2 because there?s no pathway for it to become a ?thing?. As the internet grows and ages, it?s becoming ever harder for smaller websites and individuals to break into the space ? and it?s going to stay that way.

YouTube?s not alone

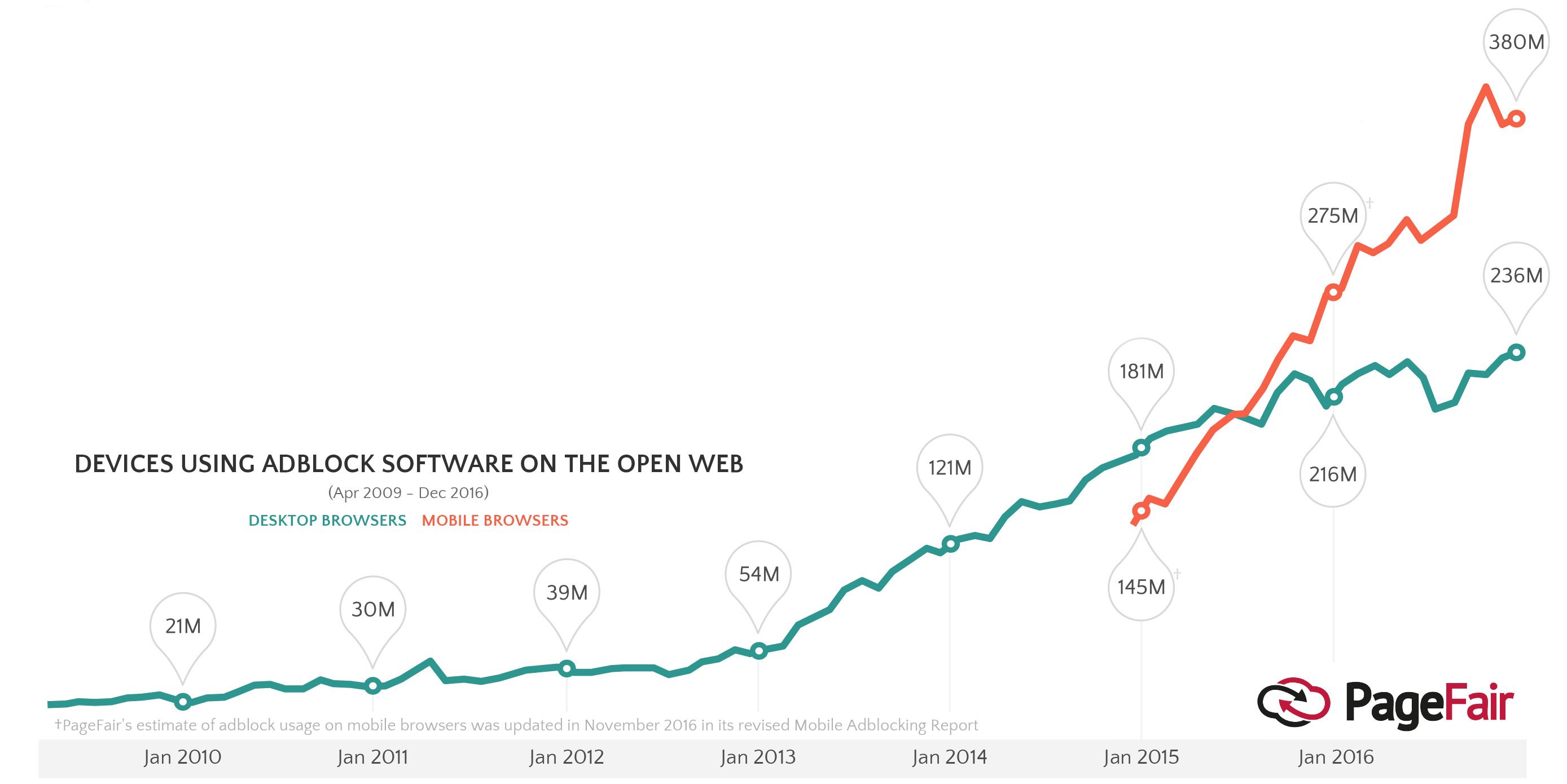

YouTube ? and the internet?s ? woes go beyond a few individual (or even huge national) controversies and a few corporations? vision for their platforms. Again, the problem is their bottom lines and share prices. The core principle of an open and apparently cost-free (if not independent) internet relied on the idea that the data gained was worth more than the opportunity cost of charging for those services. That notion is being challenged. Data is only worth as much as the ads it can sell, and the ability to sell ads is apparently decreasing every day. For now, this is hitting Google, and in particular, YouTube the hardest, since Google?s business model most heavily depends on it. Search ad clickthrough rates are down, with advertisers instead competing for top spots in Amazon rankings. Without a compelling social network outside of YouTube, AdSense purchases as a whole are down compared to native ads on content feeds like on Snapchat and Instagram. But they?re not alone in their troubles. A mere 0.06% of users click on banner ads, with under half doing so intentionally. Ad-blockers have soared in popularity in the past few years, especially among millenials and high earners ? the most valuable segments to advertisers. Young users blocking ads isn?t a good sign for the future of the industry either. With concerns about privacy on the rise, Apple and Mozilla have also added built-in ad-blockers to their respective Safari and Firefox browsers.

It?s not like Google?s blind to the problem either. Earlier this year, Google announced plans to limit ad-blocking capabilities in their Chrome browser. At the same time, the company ? along with Microsoft and Amazon ? paid out massive sums to the popular extension Adblock Plus to allow their ads through. The problem isn?t that Google isn?t aware of the problem, but that they don?t know how to pivot. Further, simply charging for services that were once free isn?t really an option either, as users have been conditioned to expect these services for free. Just look at YouTube Red ? er, Premium. If users won?t accept ads and won?t accept direct payment, what else is left?

This is the same monetization problem that successful startups across the valley like Twitter and Snap have been facing for years ? only this time, it?s on an industry-wide scale. And with ever-mounting lawsuits, regulator inquiries, and a constant onslaught of media scandals, costs sure aren?t getting any cheaper.

For the time being though, YouTube isn?t dead ? and it?s still free for anyone to post or watch. Keyboard cat may be no more (sadly, literally as well as figuratively), but bongo cat is still alive and smiling, happily playing the internet?s tunes. The way we interact with the world?s largest video sharing platform has changed, but ultimately, the internet is what we make it. Let?s make it something we all like.