The soon-to-be-retired Jet.com wanted to be the Amazon killer. Instead, it gave Walmart a fighting chance at e-commerce.

Image: Jet.com

Image: Jet.com

We gather here today to mourn the short life of Jet.com, the e-commerce startup launched in 2015, which Walmart purchased for $3.3 billion in 2016 ? and announced last month that it was shutting down. In Walmart?s Q1 earnings release, the company stated, ?Due to continued strength of the Walmart.com brand, the company will discontinue Jet.com. The acquisition of Jet.com nearly four years ago was critical to accelerating our omni strategy.?

But is this really such a loss? And what can we take away from this brand?s passing?

Jet?s early days

Say you want to compete with Amazon. How would you do it?

Marc Lore, who previously founded Diapers.com and sold it for $535 million, had an idea. Amazon competed on both price and convenience. What if a company competed only on price? With this in mind, he began working on the company that would become Jet.com.

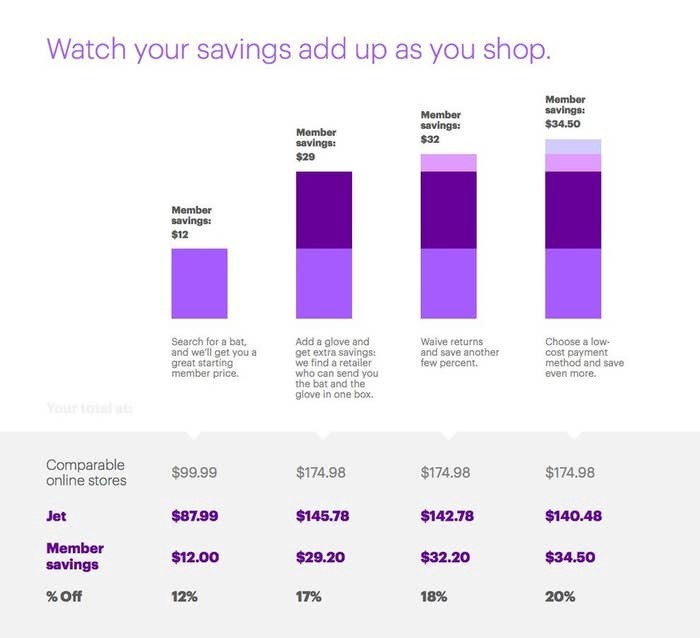

Jet?s innovation was its ?Smart Cart,? which dynamically updated the prices of goods as customers added them to their cart to give them lower prices.

Because shipping and fulfillment costs are lower when you ship from the same distribution center, if you added something from a warehouse in Texas, Jet.com could show you a lower price for other items in that warehouse. Additionally, customers could get further savings on Jet.com by using a cheaper payment method (such as a debit card) or agreeing to not return an item.

(Source: BuzzFeed News)

(Source: BuzzFeed News)

The first few months after launch, Jet actually exceeded sales expectations, so much so that it ended the $49.99 annual membership fee. But increased revenue wasn?t going to fix a more fundamental problem with Jet?s business model.

Jet?s LTV problem

The main issue with Jet was unit economics. In the early days of a startup, investors focus on the ratio of lifetime value (LTV) to customer acquisition costs (CAC), because a positive LTV-to-CAC ratio means burning cash to acquire new customers is a viable strategy in the long-term. The customers you pay to acquire today will turn you a profit in the future.

The Wall Street Journal reported purchasing 12 items for $275.55 on Jet.com, calculating that Jet?s employees had spent $518.46 on the transaction to buy those items from other sites.

However, Jet?s LTV-to-CAC ratio didn?t look so good, since the company was losing money on the bulk of its orders. To lure customers away from Amazon, Jet would pay whatever price it took to show customers the lowest possible price for a product. Given that a new e-commerce operation could not leverage strong vendor relationships to give customers a large inventory with low prices, Jet had to pay for those discounts out of its own pocket through a system that had Jet employees searching other websites for that product and ordering it on behalf of the customer.

In July 2015, the Wall Street Journal reported purchasing 12 items for $275.55 on Jet.com, calculating that Jet?s employees had spent $518.46 on the transaction to buy those items from other sites (resulting in a loss of $242.91).

Obviously, that meant the gross margins were negative for the items that were sourced this way. While these negative margins may have applied to only a fraction of the products Jet sold, discount e-commerce is not a very profitable industry to begin with, and these large losses would have eaten through the thin margins Jet earned on the rest of its sales. Making the LTV-to-CAC ratio work when you don?t have any LTV is pretty tough.

In the eyes of Marc Lore?s investors, however, if he asked to paint a masterpiece, you gave him a brush. His vision was that Jet could achieve profitability once it reached $20 billion in annual sales. At that level, Jet could leverage its market power as the gatekeeper of consumer demand to get better terms on their inventory.

Failure to build a brand

This logic might have worked, and Lore may have eventually turned around Jet?s lousy unit economics over time, if it weren?t for the fact that Jet failed to build a brand that resonated with customers in any meaningful way.

Brand is more than the colors of your logo and the copy on your website. It?s the sum of the interactions you have with your customers. The more positive interactions, the more trust you build. That?s a brand, and it takes time to build.

Amazon spent years building one of the most powerful discount brands in the world ? so powerful that most shoppers don?t even remember the brands of the products themselves.

The bottleneck to building a brand is the number of times a company interacts with a customer. It takes six to eight interactions before that customer trusts you enough to buy something.

Buying advertisements artificially scrunches down this process, but it also dramatically increases your customer acquisition costs. This is the approach Jet took.

Amazon, however, did the opposite, having spent years building one of the most powerful discount brands in the world. So powerful, in fact, that most shoppers don?t even remember the brands of the products themselves, only that they came from Amazon. I wrote about this phenomenon in my piece on Shopify:

In the past few months, I?ve purchased a spiral-bound notebook, a baking sheet, and a 24×32 picture frame. And where did I buy them? I would say ?from Amazon,? even though each one came from a different retailer.

Thus, the Amazon platform risk: Stores that are built on Amazon have better initial distribution, but consumers don?t recognize the brand. Consumers don?t often repurchase unless through Amazon, and Amazon has the power to change their algorithms or merchant terms at any time. There?s zero loyalty, except to the big A, which means there?s zero pricing power for merchants.

The flip side of the risk merchants face of seeing their brands devalued on Amazon is that it strengthens Amazon?s own brand. To consumers, cheap + convenient = Amazon.

Perhaps recognizing that it was fighting a losing battle, Jet.com relaunched its brand in September 2018. Instead of being the cheapest, Jet targeted high-income demographics like urban millennials. The company purchased Bonobos and ModCloth and integrated them into Jet?s existing site. It piloted the personal shopping service Jetblack?quite the opposite of discount retail.

There are valuable premium brands. There are valuable discount brands. Jet tried to build both, and in the process the company confused customers and ended up building neither.

Competing with Amazon

The final nail in the coffin for Jet was that even if it could find a way to have positive unit economics and a brand that consumers loved, it competed with Amazon in the wrong area. Marc Lore was hoping Jet?s retail business would eventually turn profitable. But Amazon?s retail segment was never in the moneymaking business?it?s in the customer acquisition business. Jet lost because it tried to compete with Amazon?s website instead of Amazon the business.

Instead of thinking about the margins on every product Amazon sells, think of the blended margins of selling a product and also advertising other products. Amazon has become the largest product search engine on the internet. Its advertising business is growing by more than 40% and has higher margins than the retail business. Amazon might only break even on the products, but it more than makes it up with advertising. While it would be possible for Jet to eventually also have advertising, that would require a lot of time and capital.

Jet may not have had a great brand or figured out the path to profitability, but it knew the nuts and bolts of building out an e-commerce operation.

And all of this is before you mention the customer lock-in with Amazon Prime, or Amazon Web Services, or the flurry of other businesses Amazon owns.

Not only could Amazon subsidize break-even prices with profits from other divisions, but it also could subsidize them with the margins from long-tail products that sell at a premium because they can?t be found anywhere else. Amazon has more than 12 million products. Jet had several million as well, but selling long-tail items for Jet was unprofitable. It didn?t have the buying power or third-party seller infrastructure set up to make it profitable.

Why Walmart needed Jet

Despite all these issues, Walmart purchased Jet because it needed e-commerce help.

When Walmart bought Jet in 2016 for $3.3 billion, Walmart?s e-commerce sales accounted for only 3% of its revenue, even though it had launched Walmart.com in the early 2000s.

In July 2015, Amazon first passed Walmart in market cap, and a Quartz article declared that ?the retail king has lost its crown.? Walmart needed some energy, and Marc Lore and the team from Jet were the perfect spark. They may not have had a great brand or figured out the path to profitability, but they knew the nuts and bolts of building out an e-commerce operation.

And it seemed to have worked: E-commerce is now nearly 15% of Walmart?s total sales.

With Walmart announcing the end of Jet.com, it looks like no one is mourning its death ? certainly not Walmart CEO Doug McMillon, who said he would do it all over again, and not even Jet?s employees, who had already transitioned into jobs at Walmart.com. But those same employees, led by Marc Lore, are the ones who helped grow Walmart?s e-commerce into what it is today and will turn it into a more formidable Amazon competitor in the future. The acquisition went exactly as planned.

A version of this article was originally published on Napkin Math.