Earlier this week, package delivery startup Doorman announced that it is shutting down. For those who have been following the last mile delivery space closely, Doorman?s failure should come as no surprise. The company, which had set out to revolutionize the customer experience in the parcel delivery industry, has been struggling from its early days with finding a viable business model. Only last October, it announced a sharp increase in its delivery fees to compensate for losses, a move that ? as it turns out ? only accelerated its death.

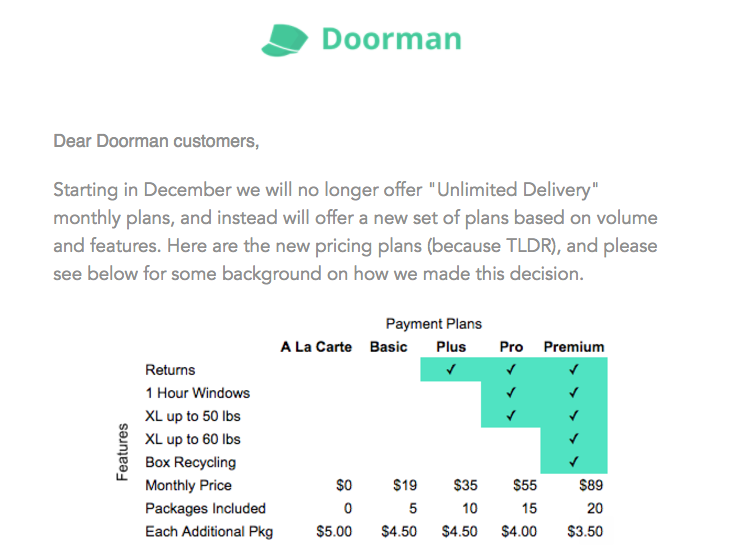

(Doorman?s announcement from October 31st, 2016):

(Doorman?s announcement from October 31st, 2016):

In this post I explain the three key mistakes that Doorman made in shaping its business models, and draw one big lesson that would help similar startups avoid a similar fate.

Also, don?t forget to follow me on Twitter.

The Doorman Model Explained ? Reinventing the Customer Experience

Doorman aimed to solve a growing pain in the lives of consumers in large cities like New York, Chicago and San Francisco. In these cities, it is generally harder for online shoppers to receive packages at their homes, especially for those living in large buildings. Often, packages left in the building?s lobby or at the recipient?s doorstep would be stolen before the recipient had the chance to pick them up. In other cases, delivery drivers who cannot access the building would leave behind the infamous ?sorry we missed you? note, sending the consumer on an annoying journey to the post office or UPS location, which often close for business early.

Doorman wanted to solve this problem by offering an evening delivery service, which always brought the package to the customer at a time window of her choice. To do that, the company guided its customers to have all their online orders shipped to a local warehouse, operated by Doorman. From there, the customer could use the Doorman app to choose her 1 or 2 hour delivery window, and a Doorman driver would deliver the package.

The service was offered for a flat fee, but Doorman also pushed its customers to buy ?unlimited delivery? subscription plans, for as little as $19 or $29 per month. These fees were later increased drastically to compensate for Doorman?s losses, but to no avail.

According to Crunchbase, the startup raised a total of $3.37 million in three rounds.

Doorman?s website

Doorman?s website

Where did Doorman go wrong?

Doorman?s failure was not a result of poor operational execution. Rather, it was due to a flawed business model and lack of focus on sustainable unit economics. I break this down into three key mistakes.

Mistake #1: going direct-to-consumer.

Anyone who shops online knows that in today?s world, free shipping is the standard. Amazon, with its obsession for delighting the customer, has made consumers so accustomed to free shipping, that any retailer who charges for standard shipping risks losing the customer. It is no wonder, therefore, that few Doorman customers were willing to pay $89 / month for its premium delivery subscription, or even pay for its less expensive subscriptions (which later all limited the number of packages a customer could get).

Doorman, of course, is not the only delivery startup that targets consumers. But unlike some of the other delivery startups, its revenue model did not account for the particular challenge of targeting consumers.

Unicorns like Instacart, Deliveroo Grubhub and other on-demand delivery startups such as Doordash and Postmates are all direct-to-consumer services. However, all these companies have an additional source of revenue on top of the delivery fee, which makes them viable businesses.

While Instacart marks up the groceries offered on its platform, and keeps some of that margin to itself, Postmates and Doordash charge a referral fee from the restaurant from which they deliver. In other words, all these startups ?own? the customer at the checkout point, and therefore take a ?cut? of the transaction. Doorman, on the other hand, only charged for the delivery after the consumer had already made the purchase from a retailer. And when consumers? willingness to pay is low ? building a business only on delivery fees is tough.

Doorman could have built a more sustainable business by working directly with retailers and charging them for the service, rather than charging the consumer. Like startup Deliv, it could have positioned itself as the last mile delivery arm for retailers, for same day or express delivery. And while retailers have more bargaining power than a single consumer does, and could try to negotiate delivery fees down, paying for deliveries is nothing new to them.

Doorman seems to have realized this at some point, and began targeting retailers as part of its offering, but that may have been too little, too late.

Mistake #2: not focusing on density.

In the delivery business, density is defined as the number of delivery stops that a driver can achieve in a given hour. A UPS driver, for example, would hit on average 9.2 stops per hour, and in some cities up to 15?20. A postman would stop at every single address on his route to deliver mail. In these high-density models, the delivery cost spreads over a large number of packages, which results in a relatively low cost per package.

Density is usually the key for achieving profitability in the delivery business. But in its mission to revolutionize the customer experience, Doorman sacrificed density and instead allowed consumers to choose narrow delivery windows, 1 or 2 hours at a time, even at times of low demand. This meant that drivers had to spend more time on the road from stop to stop, resulting in lower route efficiency and high delivery cost per package.

Another company that made a similar mistake is Shyp ? a first mile delivery startup that allowed consumers to ship anything from their home by utilizing a Shyp driver, who would show up at their door and pick-up any item within 30 minutes of a call. The $5 flat fee that Shyp collected from consumers, and any other revenue gained later in the process, were never enough to cover the high cost of sending a driver to a pick up location in such narrow time windows. Shyp simply didn?t have sufficient density. The company announced in July that it is ?significantly scaling back its operations and laying off employees to ?focus on achieving profitability.??

Delivery startups can indeed offer narrow delivery windows to delight consumers. Yet the way to provide great experience without losing one?s shirt is to reflect the true cost of the delivery to the customer, or having an additional source of revenue to cover this cost.

Doorman could have avoided this mistake by surging their delivery fees during hours of low density. Had it done so, most customers would have likely opted for the cheaper delivery windows, which, in turn, would have further increased the density for these routes and reduce the cost for every delivery. Similarly, dynamic pricing algorithms (like those used by Uber and Lyft) could even more accurately reflect the true cost to the customer, as they take into account real time data of delivery density, and calculate the cost for each additional stop that is about to be added to the route. But Doorman never incorporated these into its pricing model.

Mistake #3: not thinking unit economics.

In fact, the Doorman pricing model was never based on the actual cost of delivery. Rather than finding a sustainable unit economics model, the company made a huge bet on adoption at highly subsidized rates, with the hope that it would be able to drive down costs at some point in the future. And when wide adoption didn?t occur, it continued to lose money until the bitter end.

Doorman initially launched with an ?unlimited delivery? subscription for as low as $19/month ? which was most likely intended to be a promotional price. However, the company underestimated the risk of going to market with such a low price. With ?unlimited delivery?, customers doubled their online purchases, overusing the Doorman service and driving up delivery costs far beyond the subscription fee. CEO Zander Adell then explained in an email to Doorman?s customers that:

?unfortunately that means our original monthly plans have stopped making sense and we?re, like, losing money on a lot of you.?

Doorman then reacted with a second bet, which again, did not reflect their true costs. The company eliminated the ?unlimited delivery? subscription and significantly increased prices, capping the number of deliveries per subscription. But even then, the fee per delivery, averaging at a little less than $4, did not reflect the true delivery cost. Under its new pricing method, Doorman needed to complete at least four to six deliveries in any given hour just to breakeven on the driver, which typically earns $16?25 per hour. But four to six stops per hour is hard to achieve when the company commits to 1 hour delivery windows, and Doorman struggled to build this kind of density. In essence, Doorman made a bet that its subscriber base will grow substantially over time, which would lead to increased delivery density and lower cost per delivery.

Betting on future density is a dangerous move. Uber and Lyft may have pulled it off by introducing their Pool and Line services at heavily subsidized rates to achieve adoption, but even they recently began raising their prices to reflect the true cost of each ride. Doorman, on the other hand, never attempted to reflect its true cost to the consumer, and ultimately ran out of cash.

Conclusion

Winning in the delivery market and providing a great customer experience is hard, but not impossible. Startups that compete in this space must pay extra attention to the unit economics, and make sure they have a reasonable path to a profitable business model, rather than just bet on future density.

There are multiple ways to ensure profitable unit economics: partnering with large shippers who already have high density; owning the customer and taking a cut of each transaction; adding new channels of revenue; or even charging the customer based on the actual cost of delivery are all proven ways to achieve profitability. Targeting consumers and hoping that one day they would pay more ? is most likely not the way to get there.

What Doorman got right: Customer Experience is King.

Doorman did get one thing right. It proved that by improving the customer experience and offering more convenient delivery options, online shoppers are willing to buy more. Much more. As Adell explained:

?What we didn?t expect was that Doorman would actually change peoples? shopping behavior. Now we know that Doorman customers shop online twice as much within 6 months of signing up. Which is amazing.?

Retailers should take notice. Doorman has proven that a better delivery experience translates into higher shopper conversion rates, increased customer loyalty, and ultimately more sales.

This is especially the case with customers living in big cities like the ones Doorman served. The demographics of these customers ? on average younger, more educated, higher income earners and heavy users of online services, make them the perfect customers that every online retailer should pursue. Companies like Amazon and Wayfair already know this, and are investing disproportionally in their supply chain and last mile delivery capabilities to provide a seamless customer experience. To survive in tomorrow?s market, other retailers would have to follow suit. And that?s where delivery companies, both incumbents and startups, can ultimately create immense value for retailers.

Follow me on Twitter.