There?s a problem with cacao farming. Craft chocolate makers and consumers are both implicated. Written by a cacao farmer and chocolate maker in Ecuador.

I should start out by saying that I believe cacao farming is a noble profession. Its nobility is one of the things that first attracted me to it. I?ve been farming cacao with an increasing level of seriousness since 2008 under the auspices of a rainforest conservation project. If I didn?t have the benefit of other income streams, I would be the poorest person you know who works a full-time job ? despite the fact that this job creates the raw material for something that society values highly. This is one of the many quiet contradictions of a global economy in which specialty foods are celebrated by affluent people while the primary producers of those foods live at a subsistence level.

It?s very difficult for cacao growers to make a living in any country. From what I?ve read, West African cacao growers have it the worst, though I haven?t seen this with my own eyes. My personal experience in cacao farming is entirely limited to Ecuador, which is the native origin of cacao and home to the most prized and endangered cacao variety in the world, called Nacional. Incidentally, Ecuador is also home to the single greatest threat to heirloom cacao throughout the tropics, in the form of a cacao clone by the name of CCN-51.

The fear of an existential threat to cacao recently made its way through the news cycle, in somewhat sensational fashion. The culprit was reported to be climate change, otherwise known as global warming. From my vantage point in Ecuador, I believe money and CCN-51 are the real threats.

Don Divino at work in the valley of Piedra de Plata? one of the last bastions of heirloom Nacional cacao in Ecuador (province of Manab). Photo Credit: To?ak

Don Divino at work in the valley of Piedra de Plata? one of the last bastions of heirloom Nacional cacao in Ecuador (province of Manab). Photo Credit: To?ak

Today most cacao in Ecuador is still produced by individual growers working on small-scale family farms. Much of this cacao is organic, even though it?s usually not certified as such. Nacional cacao, in particular, has the advantage of not needing chemical inputs the way that other crops like apples and strawberries do. It prefers to grow in the partial shade of other fruit trees on hillsides that are half cultivated and half wild.

There is, however, an increasing trend toward factory-style cacao farming by large-scale corporations. For better and for worse, these plantations practice an entirely different approach to farming from that which you see in the hills of the province of Manab, which is the last true stronghold of heirloom Nacional cacao cultivation in Ecuador. The large factory-style farms in Ecuador ? in provinces like Guayas and Los Rios ? primarily grow monocultures of CCN-51, a cultivar famous for its extremely high yields and its poor flavor characteristics. Nacional cacao, meanwhile, is famous for exactly the opposite characteristics. It?s known for its poor yields and its wonderfully aromatic and nuanced flavor profile.

CCN-51 cacao tree in the province of Guayas, Ecuador. Spectacularly high yields and regrettably poor flavor characteristics.

CCN-51 cacao tree in the province of Guayas, Ecuador. Spectacularly high yields and regrettably poor flavor characteristics.

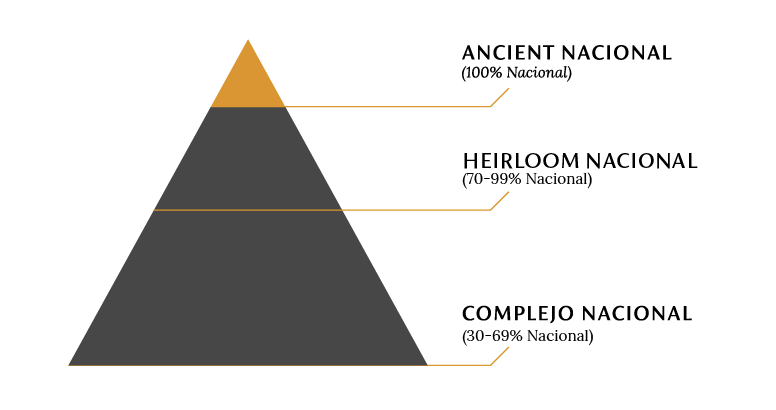

Your average CCN-51 cacao tree is about three to four times more productive than your average Nacional cacao tree ? in some cases, even more so, depending on how old the Nacional cacao tree is. Compared to the old-growth Ancient Nacional trees that To?ak harvests in Piedra de Plata, many of which are over one hundred years in age, CCN-51 produces about eight times as much per tree.

Ancient Nacional cacao tree in Piedra de Plata. Photo Credit: To?ak

Ancient Nacional cacao tree in Piedra de Plata. Photo Credit: To?ak

Most CCN-51 cacao beans are used for the mass-production of products like cocoa butter and ?candy bars? heavily laced with milk, sugar, and other additives. On the other end of the quality spectrum, single-origin dark chocolate bars sourced from Ecuador are usually produced from some version of Nacional cacao, although even this can be misleading. What cacao geneticists call ?Ancient Nacional? (100% genetically pure Nacional) scarcely exists. It is relegated to a few old trees in just a handful of valleys. For a deep dive into the history and current conservation status of Nacional cacao in Ecuador, check out ?The Near Extinction of Ancient Nacional Cacao.?

The vast majority of Ecuadorian cacao that is claimed to be ?Nacional? (for example, on the label of a dark chocolate bar) is actually a hybrid that has been crossed with any number of foreign cacao varieties. The best of these hybrids, in which the Nacional genotype represents 70?99% of the genetic composition, are still rightfully designated ?heirloom? by the Heirloom Cacao Preservation Fund. This is the upper echelon of cacao in the world. For a deeper dive into this subject, check out ?The Different Grades of Ecuadorian Cacao: a primer for distinguishing the best from the rest.?

The three grades of Nacional cacao in Ecuador. CCN-51, if it were to be included in this diagram, would sit below the pyramid. Genetically, it is comprised of 1.1% Nacional crossed with six other varieties, with IMC (45.4%) representing the largest share.

The three grades of Nacional cacao in Ecuador. CCN-51, if it were to be included in this diagram, would sit below the pyramid. Genetically, it is comprised of 1.1% Nacional crossed with six other varieties, with IMC (45.4%) representing the largest share.

The difference in flavor quality between CCN-51 and Nacional cacao is not even debated. CCN-51 is somewhat akin to those big, bright red tomatoes that look good but are bland and tasteless, at best. Dark chocolate that is produced from CCN-51 is actively bitter and astringent with a noticeable lack of secondary flavor characteristics. Heirloom Nacional cacao, on the other hand, can display fruity, floral, earthy, and nutty notes all in the same bar of dark chocolate, sometimes with an almost perfumed fragrance. There is also usually a progression of flavors that evolve over the course of the time that it takes for a piece of dark chocolate to fully dissolve on your palate ? starting on one note, passing through a few other notes, and finishing on an entirely new note. Its complexity is arguably it?s finest trait.

Nacional cacao?s comparison to wine is apt. Even the tannic structure is analogous.

Nacional cacao?s comparison to wine is apt. Even the tannic structure is analogous.

Because of this stark difference in quality, CCN-51 has become a favorite punching bag among those in the craft chocolate industry, and sadly I include myself in this group. At To?ak, we have considered ourselves sworn enemies of CCN-51 from the very beginning, and we pride ourselves on being champions of Nacional cacao. Being based in Ecuador and working directly at the source, if anything we take an even harder line. But this attitude is prevalent across the industry, even among craft chocolate makers based in the U.S. or Europe. The general rule of thumb is that Nacional cacao is coveted and CCN-51 is scorned. In the context of flavor quality, this is entirely justified.

The problem is that the prices paid to Ecuadorian cacao growers don?t reflect the disparity of both quality and yield between these two distinct classes of cacao. Nacional cacao growers who don?t have the luxury of a direct trade relationship with a chocolate maker (eg., the growers in Piedra de Plata with To?ak) usually end up selling their cacao to local middlemen who pay the same low price for all classes of cacao regardless of quality. These local middleman, who can be found in almost every mid-sized town in provinces like Manab, pay about $0.25 per pound of ?wet cacao,? which means freshly-harvested cacao beans that have not yet been fermented or dried. Whether the beans are heirloom Nacional or CCN-51, or certified organic or not, the price is usually the same ? quoted in terms of a hundred-pound sack called a ?quintal.?

?Wet cacao? during the first 24 hours of fermentation. Photo Credit: To?ak

?Wet cacao? during the first 24 hours of fermentation. Photo Credit: To?ak

In a few rare cases, some large cacao cooperatives, such as Fortaleza del Valle, exclusively buy Nacional cacao (of various grades, not always heirloom) and pay almost twice the market price ? usually in the range of $0.45 per pound of wet cacao, with a 10% premium if it?s certified organic. This is a step in the right direction.

The few bean-to-bar chocolate makers who purchase their cacao directly from farmers usually don?t pay much higher than this price, although they typically pay for ?dry cacao,? which carries a different price. ?Dry cacao? refers to cacao that has already been fermented and dried by someone else ? for example, the farmers themselves or by a cooperative like Fortaleza del Valle.

Comparing wet cacao prices with dry cacao prices is an apples-to-oranges comparison. Dry cacao prices are generally more than three times higher than wet cacao prices per pound, for the simple reason that wet cacao is reduced to one third of its weight over the course of the drying process. A modest premium is also usually added for the work required to do the fermenting and drying. Thus it is customary for the lowest grades of cacao to fetch prices of about $1 per pound of dry cacao ($2.20 per kilogram).

Fermented and dried heirloom Nacional cacao beans. Photo Credit: To?ak

Fermented and dried heirloom Nacional cacao beans. Photo Credit: To?ak

This price is largely generated from the ICCO commodity price, which fixes an international price for dry cacao beans per metric ton. Over the course of the year 2018, the median monthly average ICCO price was $2,201, which conveniently comes out to $2.20 per kilogram (exactly $1.00/pound). To put this number in a practical context, most small-scale cacao growers in Ecuador produce less than 2,000 kilograms of dry cacao per year. This equates to annual earnings of less than $4,400, which is about 20% less than minimum wage in Ecuador ($5,319/year). When you take into account the expenses that the farmer may incur (such as fertilizer, irrigation equipment, in some cases additional labor, etc.), this deficit grows wider.

Fair Trade only marginally improves the situation. Fair Trade certification requires that farmers are paid at least $2.40/kg, with a 12.5% premium for certified organic cacao and an additional 10% premium paid into a communal fund for farmers to spend on social projects. Fair Trade certification also requires fair labor practices and other standards that are, of course, constructive, but in terms of the prices paid to farmers, Fair Trade has a marginal impact. ?Fair,? in this case, is a relative term. Fair according to whom?

Before the days of To?ak, a chocolate maker once offered to buy the cacao I grow in the Jama-Coaque Reserve. The price he offered was dutifully in line with Fair Trade standards, although I didn?t know this at the time. I merely evaluated this price at face value and judged it to be somewhat of an insult to my time and effort. Little things like this were part of the reason I ultimately co-founded To?ak. I recognized that being a cacao farmer at the mercy of cacao buyers is a weak position to find oneself in this economy. My immediate solution was to become a cacao buyer (in the form of a chocolate maker with To?ak) without giving up my job as a cacao supplier (in the form of a farmer with the non-profit foundation Third Millennium Alliance). Thus I became both sides of the coin, which is quite rare in this industry.

The author tending to a cacao sapling in the Jama-Coaque Reserve. Photo Credit: Juan Carlos Bayas.

The author tending to a cacao sapling in the Jama-Coaque Reserve. Photo Credit: Juan Carlos Bayas.

Admittedly my situation is different from the average cacao farmer in Ecuador and most other countries. I wasn?t born into this profession, it was something I chose to do because it interests me and I enjoy doing it. I also have a day job (or two) that keeps me financially afloat aside from farming. If I didn?t have those other income streams and I entirely depended on farming for my livelihood, I wouldn?t have been able to buy the computer on which I?m typing this. Maybe it takes a semi-insider/semi-outsider like me to call attention to something which is mostly misunderstood on the outside and un-voiced from the inside.

In any event, this dual position of seller and buyer has brought me into close contact with the CCN-51 conundrum. It has given me the opportunity to look at the issue from both angles, and in the context of individual farmers we work with as well as the industry as a whole. When you start by looking at how individual people are affected, and then zoom out to the distance of society at large, the nature of this problem takes a different shape.

The unsustainably low price of cacao ? of all classes ? have prompted many farmers to abandon cacao. A good number of these farmers eventually abandon their land altogether. They relocate their families to the over-populated cities, armed with skill sets that are not adapted to the urban job market, and this leads to things like unemployment and crime.

There are also many cacao growers who don?t want to abandon farming. They like their land and they like their community. They want to continue working in the countryside, and cacao farming is what they know best. Therefore many of these farmers opt to replace their old Nacional cacao trees with CCN-51 trees. The thought process behind this decision is mathematical: CCN-51 produces at least three times as much as Nacional and generally earns the same price per pound. Thus they triple their income.

When people in the craft chocolate industry ? again, myself included ? hear about something like this, the tendency is to say (or at least think) something along the lines of: ?tsk tsk, cacao farmer! How dare you cut down your low-yield heirloom trees in favor of high-yield CCN-51 trees? You?re killing those delicate notes of orange blossom in my chocolate!?

The cacao farmer, in turn, usually apologizes for this. He really didn?t mean to cause any harm. Meanwhile inside his own head he?s saying, ?stupid chocolate maker, I?m just trying to make a living here. I?m only growing CCN-51 because you kept paying me crap prices for the good stuff. What do you expect??

He has a point. When looked at in this light, the craft chocolate industry is the hypocrite and the cacao farmer is the rational actor. From an economic perspective, the decision to grow CCN-51 in place of heirloom Nacional cacao is entirely logical so long as the buyers of cacao fail to pay a price that recognizes the yield/quality discrepancy between these two classes of cacao.

Don Arnoldo ? the caretaker of numerous DNA-verified Ancient Nacional trees ? in his farm in PIedra de Plata.

Don Arnoldo ? the caretaker of numerous DNA-verified Ancient Nacional trees ? in his farm in PIedra de Plata.

This hypocrisy is not limited to chocolate makers. It also extends to some of the consumers of craft chocolate, who are happy to buy small-batch single-origin dark chocolate bars made from heirloom varieties such as Nacional and Criollo, but who balk at the thought of paying three or four times the price relative to mass-produced dark chocolate bars. The problem runs up and down the entirety of the supply chain, and much of it has to do with pricing.

At To?ak, our idea was to shake up this paradigm by creating the most extravagant dark chocolate bar on the planet, with the price to match ? an admittedly extreme strategy. Not only do we charge the highest price in the world for our chocolate, but we also make a point to pay the highest prices for cacao. Even for our ?lowest grade? of cacao, which is still heirloom Nacional in the top one percentile of global quality standards, we pay 4x more than the standard market price. For our highest grade of cacao ? the Ancient Nacional trees in Piedra de Plata, DNA-profiled and rigorously selected ? we pay 8x the standard price, which comes out to $200 per ?quintal? of wet cacao.

All four grades of Ecuadorian cacao

All four grades of Ecuadorian cacao

We physically work with the growers in Piedra de Plata on harvest day and then we ferment and dry this cacao ourselves ? which is another thing that is rare in the craft chocolate industry. After losing about 66% of its weight during the drying process, the cacao we harvest is reduced by an additional 40% during the bean selection process. Beans that don?t pass our criteria are used for experiments or for home consumption by those of us who work at To?ak ? one of the perks of the job.

Among the beans that we ultimately convert into chocolate, a further 40% of this weight is lost during roasting and triple-winnowing of the husks. From each hundred-pound sack of wet cacao, we?re left with twelve pounds of potentially usable cacao that is ground and refined into a uniform mass, before the addition of cane sugar. Not all of this cacao is ultimately destined for commercialization. Much of it is held back for aging in casks or other forms, and only some of these aged editions are released to the public ? usually less than half, which comes out to about five pounds.

After converting this number to the metric system, which is what most international cacao prices are quoted in, this leaves us with 2.28 kilograms, which we initially purchased for $200. This doesn?t include all of the costs we assume during our in-house fermentation and drying process, nor transport, nor production of the chocolate itself and the aging process, which requires the import of specialty casks to Ecuador from around the world (and the exorbitant customs duty that comes with them.) This also doesn?t include any of our packaging ? which is painstakingly sourced and in many cases handmade by local artisans ? nor all the salaries for a team of people who work full-time on making all of this happen. Excluding all of those extra costs, our highest grade of cacao costs us $87.71 per kilogram.

To?ak?s Vintage 2015 edition aged for three years in a Laphroaig Scotch whisky cask.

To?ak?s Vintage 2015 edition aged for three years in a Laphroaig Scotch whisky cask.

To bring this discussion back to the subject of farming, it?s important to remember (for those of us at To?ak as well) that all of the above is predicated on the work that is done at the farm. Any maker of high-quality chocolate ? whether they are based in the country of origin or not ? requires someone to do the growing of the high-quality cacao used to make their chocolate. This only happens when the revenue earned for growing high-quality cacao is at least equal to ? if not in excess of ? the revenue earned by growing low-quality and high-yield clones like CCN-51. Thus the question that we ask ourselves is this: is a price premium of 4?8x above the market price enough?

Again, I look at this question from both sides. From the perspective of a cacao farmer, I would say that this is the minimum acceptable price for high-quality cacao. I currently have some young Ancient Nacional trees growing in the Jama-Coaque Reserve ? sourced by To?ak, in fact ? that will reach productive age within a few years. Once they do, I would not sell cacao beans from these particular trees to anyone ? including To?ak ? for anything less than $200 per quintal. This judgement is based on what it costs us to cultivate these parcels of rare and finicky cacao. Granted, this is an exceptional case ? we commit much more time and resources to each tree than most farmers do ? but this is what is required to grow these trees with success. As it currently stands, a price premium of 8x would barely cover those costs, leaving a small margin to reinvest into the project.

That?s the way I see it from the perspective of a seller, and I?m not entirely alone in this sentiment. A friend of mine grows cacao in the Galapagos islands. A foreign bean-to-bar chocolate company recently offered her 3x the market price for her cacao? an incredible offer, relative to the market. But she refused it without hesitation. For her, that price simply isn?t worth the time and effort she puts in to her work. She?s originally from Europe and I?m originally from the U.S., and perhaps this explains our higher price standards. But to the extent that it does, what does this say about the industry as a whole? In my opinion, it implies that the entire chocolate industry ? including the bean-to-bar wing ? is predicated on purchasing raw materials at price levels that only apply to growers from developing countries.

Now from a buyers perspective ? as a bean-to-bar chocolate maker and entrepreneur ? I recognize that a business can only survive if it generates revenues in excess (or at least equal to) its costs. To?ak does not have the benefit of being owned by uber-wealthy people with bottomless resources. It?s owned by a handful of people who have invested their life savings in this venture, with no more money to spare. The 4?8x price premium is what we ? as a small business ? can afford to pay without cutting ourselves off at the knees.

The problem of cacao pricing becomes more manageable when chocolate consumers are willing to share some of this cost, and this is what?s starting to happen. As the market for specialty chocolate and other cacao-based products continues to evolve, the prices that consumers are willing to pay for quality are slowly moving into alignment with the prices that chocolate makers need to pay cacao growers to incentivize the cultivation of heirloom cacao. And by this, I don?t mean paying prices to farmers that narrowly exceed basic levels of subsistence. I mean prices that allow for the livelihood that any high-quality craftsman would rightfully expect.

Harvest day in Piedra de Plata during the author?s heavy beard phase.

Harvest day in Piedra de Plata during the author?s heavy beard phase.

In terms of what consumers can do, paying only a few dollars for a single-origin dark chocolate bar is clearly not enough. But I?m also not claiming that everyone in the world should be obliged to spend the amount of money that To?ak charges for its vintage cask-aged chocolate bars. There is a happy medium somewhere in between those two extremes. And this is what we?re beginning to see. We believe the market as a whole ? in the sense of a tripartite alliance of cacao farmers, chocolate makers, and consumers ? is headed in the right direction.

This vision does not entirely exclude CCN-51 or other high-yield cultivars from the global cacao landscape. The fact remains that this planet is heavily populated with humans, and many of us humans want to eat chocolate on a regular basis ? hence the trend toward high-yield cacao varieties. It?s quite logical. The dumbing down of flavor is an unintended consequence of agronomic evolution toward an increasingly massive global market.

In terms of charting a path forward, a dual approach is probably necessary. Cacao breeding programs aimed at increasing yields ? by large corporations and agricultural institutes alike ? is something that should and probably must continue, as long as humans continue to dominate the planet. At the same time, we would also be wise to preserve heirloom varieties that are blessed with characteristics that many of the high-yield clones do not have, such as quality and depth of flavor. If not, what are we all living for?

A dual approach like this is probably the closest we can get to the proverbial win-win scenario. A world with only heirloom cacao varieties would fail to satisfy global demand, and a world with only high-yield clones would literally be tasteless. If humanity ever gets to a point where the quality and complexity of food is entirely sacrificed for the sake of quantity ? in the form of the lowest common denominator ? we?re in trouble. For an eerie illustration of this latter scenario, watch the sci-fi classic ?Soylent Green.?

It bears mentioning that urban foodies with discerning palates are not the only beneficiaries of agricultural diversity. Taking care of our heirloom varieties ? of all foods, not only cacao ? also serves as a bulwark against large-scale crop failures that often occur to specific cultivars once they reach global dominance. A case in point is the near-collapse of the global banana supply when Panama Disease brought down the Gros Michael cultivar in the 1950s. More than a half century later, it?s happening again; Panama Disease is now attacking the Cavendish banana, which rose up to take Gros Michael?s place as the dominant cultivar. Despite the fact that there are over five hundred edible varieties of banana, most people on the planet today only know the Cavendish, because this is what is cultivated and exported and sold throughout the world. Now it?s facing an existential threat.

Plant diseases evolve to disrupt specific cultivars all the time ? it?s a part of nature. But when one cultivar becomes the dominant global cultivar, an opportunistic mutation in an otherwise ordinary plant pathogen can single-handedly crush the economies of entire nations and threaten the global food supply. This is exactly what happened to Nacional cacao in the early 1900s. At the time, Nacional was the only cacao variety grown in the coastal region of Ecuador, which was the leading cacao producer in the world. Not one but two diseases ? Frosty Pod and Witches? Broom ? struck Ecuadorian cacao in back-to-back fashion starting in 1916. As a consequence, production fell by 77% over the next fifteen years, the economy collapsed, and the world suffered a shortage of cacao for years.

In time, Ecuador?s cacao industry recovered, thanks in part to increasing genetic diversity. The chocolate maker in me laments the fact that 100% pure Nacional cacao is nearly extinct, but the influx of foreign varieties of cacao over the course of the last century has created a biologically healthier agricultural landscape in Ecuador. At least, until recently.

CCN-51 was first developed in 1965 and released to the public in 1984, but it wasn?t actively promoted until 1999. According to Ecuador?s Ministry of Agriculture, CCN-51 cacao represents 90% of all cacao planted in Ecuador over the last twenty years, and it now comprises 70% of all cacao that is produced in this country. A similar process is now unfolding in Peru, Colombia, and other cacao-producing nations as far as Africa. While many of the large confectionery corporations are heavily promoting the continued expansion of CCN-51, it is up to relatively small actors to play the large role of preserving heirloom varieties before they?re lost.

To this effect, To?ak and Third Millennium Alliance have teamed up to develop a genetic bank of 100% Ancient Nacional cacao trees in the Jama-Coaque Reserve, thanks in part to the help of other proactive organizations like the Heirloom Cacao Preservation Fund (HCP), which is an offshoot of the Fine Chocolate Industry Association (FCIA). But efforts like this are going against the tide. A study by National Geographic reported that 93% of varieties in food seeds were lost over the eighty-year period of 1903?1983. One can assume that this percentage has only risen in the last thirty-five years.

Planting one of the DNA-verified 100% pure Ancient Nacional seedlings (sourced from Piedra de Plata) in the Jama-Coaque Reserve?s ?Genetic Bank.? In three years, this single seedling will grow enough vegetative material to reproduce dozens of Ancient Nacional trees each year, to be distributed to any cacao grower in Ecuador who wants to be part of this renaissance.

Planting one of the DNA-verified 100% pure Ancient Nacional seedlings (sourced from Piedra de Plata) in the Jama-Coaque Reserve?s ?Genetic Bank.? In three years, this single seedling will grow enough vegetative material to reproduce dozens of Ancient Nacional trees each year, to be distributed to any cacao grower in Ecuador who wants to be part of this renaissance.

And yet, paradoxically, food culture is currently in the midst of a worldwide boom. This same trend is also playing out in the realm of chocolate. Cacao was considered sacred by almost every single culture it touched for thousands of years, up until the advent of industrial food production in the twentieth century. Now we seem to be coming full-circle. With each passing year, more and more people are tuning into the fact that dark chocolate deserves to be revered on the level of fine wine, in terms of flavor complexity and the craftsmanship required to produce it.

Meanwhile, cacao itself has become the darling of the health food movement and is even reclaiming a place in spiritual life. ?Cacao ceremonies,? modeled somewhat in the format of ayahuasca ceremonies, have almost become common in places like the San Francisco Bay Area, and this seems to be spreading to other metropolitan areas throughout North America and Europe.

All of this is to say that the fruit which cacao farmers bring to life ? so that the rest of the world may enjoy its many benefits ? is something that is highly valued in society today. In economic terms, the chocolate industry is currently valued at $100 billion, and is expected to reach $160 billion by 2024. Hundreds of millions, if not billions, of people happily consume ? in one way or another ? the fruit that is grown on these trees. Why must the men and women who cultivate these trees be relegated to poverty? How is this not a contradiction that ought to be addressed?

Money is part of this equation, but it?s not the only part. There is also the matter of pride and dignity that is at stake. By the end of my lifetime, it is my hope that the profession of cacao cultivation in countries like Ecuador becomes as respected and well-remunerated as the profession of viticulture in places like Napa and Bordeaux. This is to say that none of us cacao farmers expect to ever get rich off this job, but we also don?t want to be the poorest person in the room at all times. And a little respect would be nice ? respect from society at large as well as self-respect.

Cacao is older than wine, but viticulture is (at this point) far more advanced and respected than cacao cultivation.

Cacao is older than wine, but viticulture is (at this point) far more advanced and respected than cacao cultivation.

As it currently stands, the profession of cacao farming is most certainly not respected on par with the profession of viticulture, for reasons that are cultural and educational as well as economic ? and of course all three of those elements are interconnected. A good many people who work in viticulture have been trained in universities and approach their jobs with a level of professionalism that is rarely seen in small-scale cacao farms.

Access to education is part of this story. According to a 2011 survey of small-scale cacao farmers associated with Fortaleza del Valle, less than 28% completed high school, only 2% pursued higher education, and the rest received a primary education or less. Lesser levels of education combined with minimal economic incentive are not fertile conditions for high-quality performance in any field, including agriculture ? and this certainly applies to the cacao sector. Despite the unparalleled genetic and flavor quality of cacao in Ecuador, the cultivation and post-harvest quality of cacao has much room to improve.

On the education side of the equation, this is starting to change. University enrollment among rural students in Ecuador increased by 118% between 2007 and 2016, and this includes students pursuing a degree in the field of agriculture. Most of the technical jobs available in the cacao sector, however, are offered by the large factory-farm operations. There is little incentive and few opportunities for educated professionals in Ecuador to farm heirloom cacao in on a small- or medium-scale, although this is not tremendously different than the situation in most countries. How many university-educated Americans or French students go into small-scale farming for living? Viticulture seems to be the exception this rule.

And yet, viticulture is an exception. Viticulture draws people to it as a profession by virtue of the fact that many people think of wine (and the grapes that produce it) as something that stands on a level higher than most other crops and agricultural products. Considering that the flavor complexity of chocolate surpasses that of wine, and it is equally if not more beloved than wine by hundreds of millions of people, perhaps cacao cultivation in Ecuador can follow somewhat in the footsteps of viticulture in places like Napa and Bordeaux.

Servio Pachard ? fourth-generation cacao farmer and To?ak?s Post-Harvest Master ? is an exemplar in Ecuador for combining long-standing family roots in cacao farming with world-class expertise.

Servio Pachard ? fourth-generation cacao farmer and To?ak?s Post-Harvest Master ? is an exemplar in Ecuador for combining long-standing family roots in cacao farming with world-class expertise.

If it does, and low-quantity/high-quality cacao cultivation assumes a new level of importance both socially and economically, it will draw more educated and passionate people into the profession. And this, in turn, will increase the quality of cacao that is cultivated, which in turn should increase prices ? both for cacao and the chocolate that is produced from it. It?s something of a chicken-and-egg scenario, but once the cycle is spun into action, a positive feedback loop quickly develops. Cacao becomes less of a commodity and more of a delicacy ? as it was for thousands of years.

Cacao farming in Ecuador currently stands at the precipice of an interesting transition, which corresponds to the transition taking place in the craft chocolate industry, albeit with a few years of lag-time. Fine dark chocolate is increasingly valued in society today, and so is cacao. Perhaps in a few more years, this perceived value will also extend to the people who grow it.

This is not to say that things are so terrible now, because they?re not ? at least not in Ecuador. All things considered, cacao farmers are quite fortunate ? and I am proud to include myself in this category of lucky souls. We get to spend our days working outdoors, in a green and beautiful land of endless summer. We give life to trees and watch them grow up and then we create something special with the fruit that is born on their limbs. Aside from the economic stuff, we?re blessed.

To learn the origin story of the Jama-Coaque Reserve, check out ?How We Made a Rainforest Preserve.? To learn more about To?ak Chocolate, visit www.toakchocolate.com.

The cacao farmer?s office: the Jama-Coaque Reserve, province of Manab Ecuador.

The cacao farmer?s office: the Jama-Coaque Reserve, province of Manab Ecuador.