Coffee for breakfast. Credit: Sam Howzit, Flickr.com

Coffee for breakfast. Credit: Sam Howzit, Flickr.com

Time-restricted feeding is a particular type of intermittent fasting, often practiced among those who want to time their food intake with their circadian rhythm, that involves compressing meals into a narrower window than most people in modern societies are used to. Sometimes this regimen involves skipping a meal, such as breakfast or dinner. But whether you fast 12 hours per day, 16 hours per day, 24 hours every other day (alternate day fasting), only between meals or when you are sleeping, how and when you break your fasts matters.

We recommend talking to your doctor before trying any intermittent fasting routine, especially before fasting for 24 or more hours at a time.

LIFE Fasting Tracker on the App Store

Read reviews, compare customer ratings, see screenshots, and learn more about LIFE Fasting Tracker. Download LIFE?

itunes.apple.com

Ivan Blazquez started practicing prolonged nightly fasting after reading Ruth Patterson and colleagues? 2016 study showing that prolonged fasting (fasting for 13 hours or more) overnight influences metabolic processes and potentially carcinogenesis, or the formation of cancerous cells. In fact, this type of fasting has been associated with a reduced risk of cancer, in small human studies. Ivan says that his fasting ?sweet spot? is around 9 to 12 hours every night, with an occasional 13- or 14-hour nightly fast every week or so.

Ivan Blazquez.

Ivan Blazquez.

As an ACSM certified exercise physiologist with a master?s degree in exercise physiology, Ivan regularly scours the scientific literature for information on fasting, weight-loss, training and metabolic health. He?s found evidence of intermittent fasting benefits for health and fitness, but he?s also found that fasting comes with its caveats, especially for healthy individuals and athletes. One of these caveats is that when and how we re-feed might matter to how our bodies react to fasting. The potential benefits of fasting include improved metabolic health, autophagy and breakdown of senescent cells.

Ivan has competed in close to 50 bodybuilding competitions and triathlons. ?I have a unique understanding of fat loss from multiple perspectives, as a bodybuilder, a triathlete and a personal trainer,? Ivan said. ?I first learned about intermittent fasting from a Facebook friend in the UK who was practicing it. When I researched it more, I realized it was quite popular.?

It?s no secret that research on intermittent fasting is still in its infancy, with most research findings coming from animal models. With this in mind, Ivan takes a moderate approach to prolonged fasts. He experiments with 24-hour and longer fasts a few times per year. But current human evidence supports trying shorter fasts to glean the benefits of energy restriction without risking any unforeseen impacts of longer fasts.

Ivan typically only eats three meals each day, making a point not to snack in between. He does so primarily to stay lean, but also to kick-start his body?s self-detoxification process, known as autophagy. In this process, old, damaged and senescent cells are broken down and recycled, promoting cellular replenishment in tissues including skeletal muscle. Autophagy can be prompted by prolonged fasts, but also potentially by shorter overnight fasts and exercise. Ivan points to a 2017 study in Cell Metabolism showing that isocaloric twice-a-day (ITAD) feeding promotes diverse metabolic benefits in mice and activates autophagy in multiple tissues. This study, like many others on intermittent fasting, was conducted in mice, so there are questions as to how well the findings transfer to humans. But the underlying molecular mechanisms theoretically apply to humans, too.

?Fasting has taught me to appreciate catabolism, where our bodies are breaking down and oxidizing molecules,? Ivan said. ?I?ve studied many different foods and their effects associated with fat loss, from adiponectin, to fiber, to herbal teas. I?ve also studied the fat-loss effects of exercise, both in the fasted state and the fed state. But in experimenting and reading more about intermittent fasting, I learned about the autophagy and detoxification benefits of going without food for hours at a time. Our body has amazing and beautiful adaptive responses to sustain homeostasis without food. In an American society that is struggling with body weight and health due to an overconsumption of food, fasting shines.?

Plant-based. Marco Verch, Flickr.com

Plant-based. Marco Verch, Flickr.com

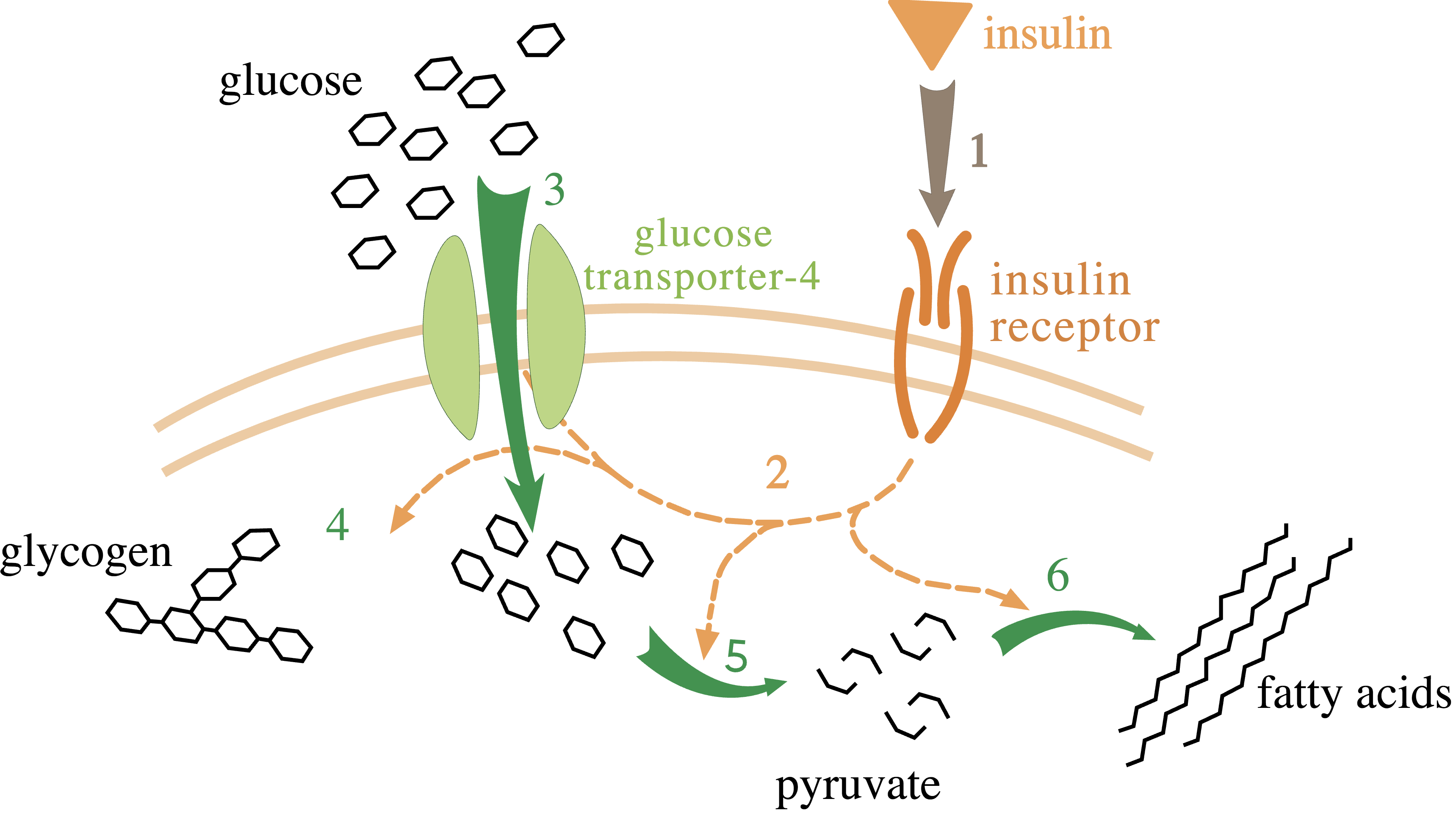

At the molecular level, as studied in animal models, intermittent fasting over time has been linked to reduced inflammation and oxidative damage within cells and tissues, optimized energy metabolism and cellular protection. Fasting for 12 hours or more prompts the body into gluconeogenesis, a catabolic state relying on endogenous glucose, and some mild ketosis, a state of breaking down and burning fats. Fasting impacts the insulin signaling pathway. It lowers insulin-growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which at high levels can contribute to insulin resistance, and potentially rids the body of inflammatory, ill-functioning senescent cells, which in turn can improve cellular functioning and metabolic flexibility (the ability of cells to switch seamlessly between fuel sources such as sugars and fats) in aging tissues.

?In humans, depending upon their level of physical activity, 12 to 24 hr of fasting typically results in a 20% or greater decrease in serum glucose and depletion of the hepatic glycogen, accompanied by a switch to a metabolic mode in which nonhepatic glucose, fat-derived ketone bodies, and free fatty acids are used as energy sources.? ? Longo & Mattson, 2014

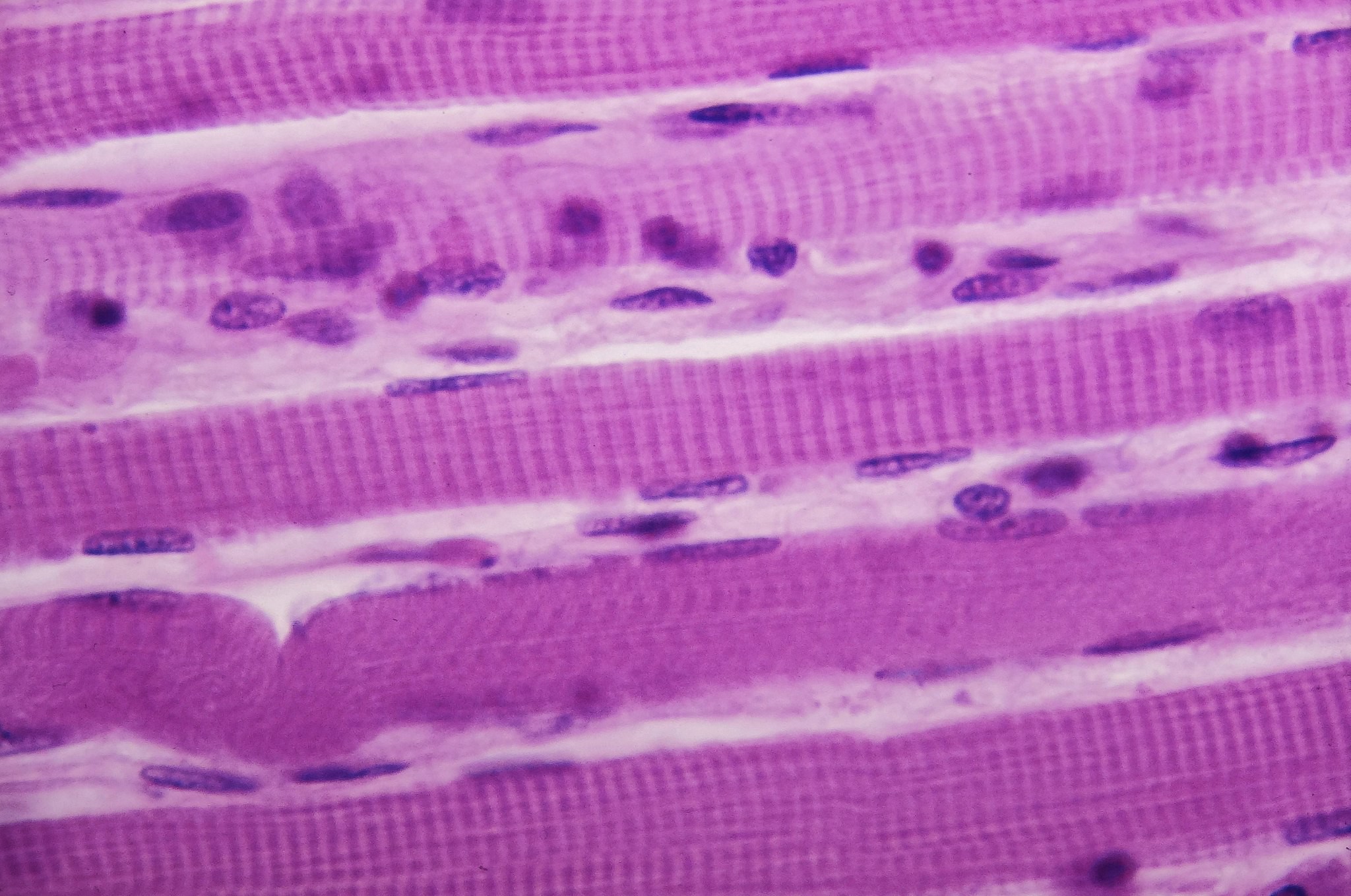

But some of the benefits of daily fasting, or rather the effects of how we break our fasts, could depend on timing. The refeeding phase of intermittent fasting can be just as important as the fasting phase, in terms of both timing and what we eat. Refeeding after a fast prompts an influx of nutrients and cellular regeneration. However, fasts longer that 40 hours have been associated with acute insulin resistance in the skeletal muscle in some people upon refeeding, due to an adaption of the muscle to low glucose availability, and lipid breakdown and accumulation in muscle cells. It could be important for healthy individuals, or anyone for that matter, not to break a long fast with a sugary or high glycemic index meal, although exercise at the end of a fast might help.

Muscle fibres. Credit: Rollroboter, Wikimedia.

Muscle fibres. Credit: Rollroboter, Wikimedia.

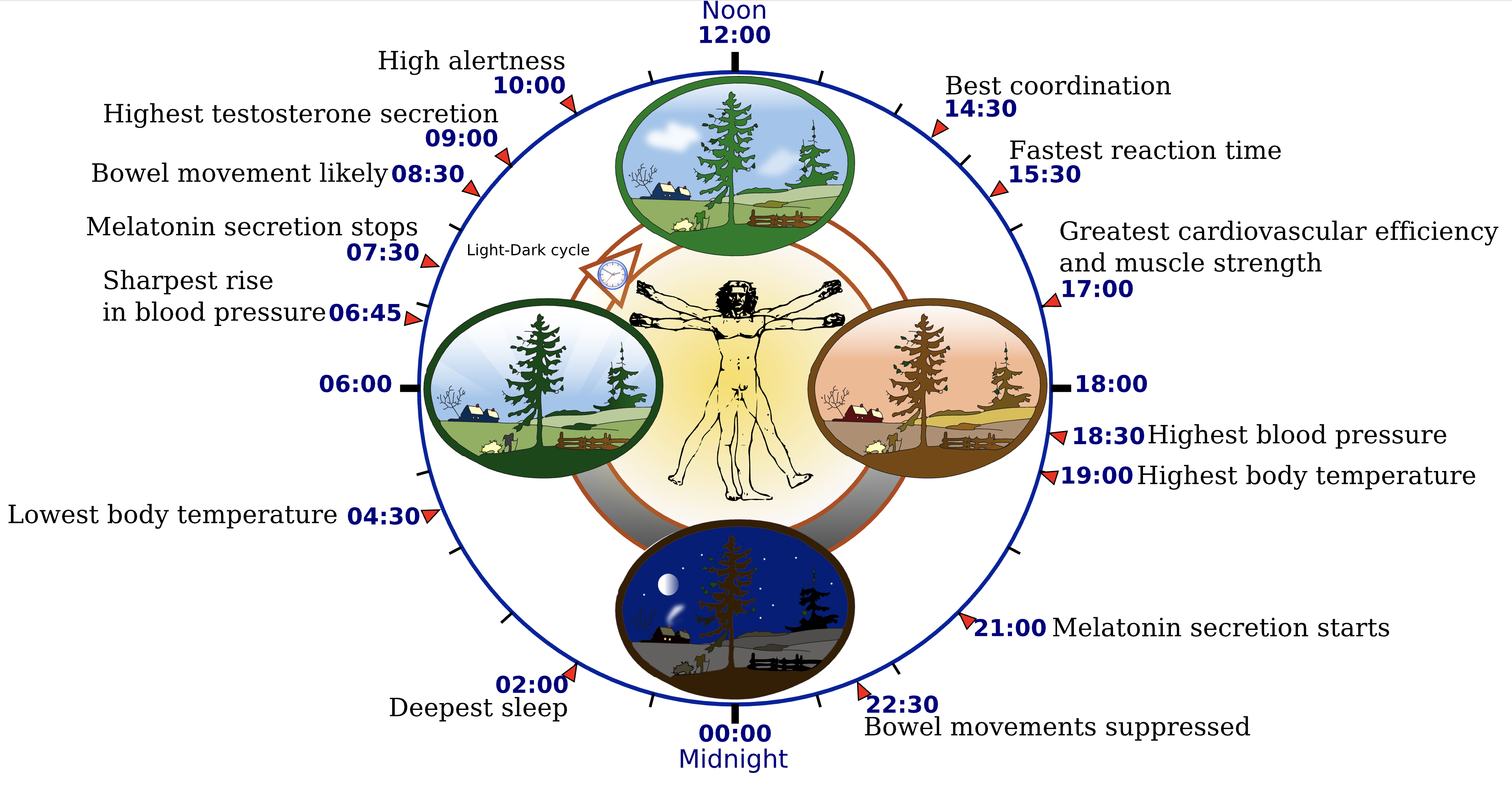

Ivan says he is careful to break his fasts in tune with his body?s circadian rhythm. This is a biological process guided by our sleep-wake cycle and light exposure, in which the activity of signaling pathways and molecules within our bodies, including melatonin and growth hormones, vary throughout the day and night. Our bodies need sleep and the increased production of growth hormones during sleep to stay metabolically healthy. But the circadian rhythm of these signaling pathways and molecules can also lead us to be more insulin resistant at certain times of the day ? especially in the evening. The circadian clock has been closely linked to metabolism and vice versa, to how our mitochondria function and how our cells use different fuel sources. A lack of sleep or a series of nights with short or impaired sleep, for example, can lead to a reduction in adipocyte (fat cell) insulin sensitivity.

A diagram based on ?The Body Clock Guide to Better Health? by Michael Smolensky and Lynne Lamberg; Henry Holt and Company, Publishers (2000).

A diagram based on ?The Body Clock Guide to Better Health? by Michael Smolensky and Lynne Lamberg; Henry Holt and Company, Publishers (2000).

?Our relatively recent human ancestors (50,000 years ago) needed to eat and forage for food during the day and fast and sleep at night. However, modern schedules often disrupt our outside worlds by exposing us to light and feeding at nonoptimal times, while our inside worlds remain tied to the phase of the internal clock. On the basis of this hypothesis, it is possible that the dissonance between internal physiology and external behavior caused by our modern lifestyles contribute to metabolic dysfunction and disease.? ? Circadian rhythms and metabolism: from the brain to the gut and back again, Cribbet et al., 2016

?If I decide to do a longer fast, up to 16 hours, I do it by eating an early dinner or occasionally skipping dinner,? Ivan said. ?This is based on a recent [but small scale] study showing breakfast skipping (front-end fasting) can create low-level inflammation and acute muscle glucose intolerance immediately after refeeding at lunch, whereas dinner skipping (back-end fasting) wasn?t associated with such adverse effects. I usually eat a regular carb-rich breakfast such as oatmeal or muesli, but if I fast during the day and eat a late breakfast or perhaps skip breakfast, I eat a lower-carb meal such as a tofu bowl to avoid elevated blood sugar.?

It may be important for individuals experimenting with intermittent fasting to track their blood sugar, to figure out the fasting schedule and post-fast meals that work best for them, to maximize metabolic flexibility and health.

Ivan also uses moderate exercise and resistance training to stimulate autophagy, and is careful about how he times his fasts and refeeding around his workouts to enhance workout performance, reduce fatigue and avoid any negative side-effects of a short-term reduced ability of muscle cells to take in glucose after prolonged fasting. As an athlete, however, his dietary needs are likely different from others fasting to lose weight or for other specific health reasons.

Findings from a 2015 study in the Journal of Applied Physiology demonstrate that autophagy signaling is activated in human skeletal muscle after 60 minutes of exercise. Autophagy from exercise and fasting can actually help build new muscle, in moderation, and is closely tied to metabolism. Autophagy is activated by the AMPK-mTOR-ULK1 signaling pathway. Insulin helps to tell mTOR, which prompts cell growth and proliferation, to ?go,? while AMPK, activated by exercise and fasting, slows it down. The autophagy effect of exercise, as well as fat oxidation, might be heightened if exercise is followed by several hours of fasting, as opposed to the quick refeeding that the typical high-performance athlete is accustomed to. This has convinced Ivan to eat in the morning before his workouts and then to fast up to 8 hours after intense exercise, instead of beforehand. If he exercises while fasted, Ivan opts for an easy or recovery workout followed by a carb-light meal to avoid a blood sugar spike.

Glucose metabolism, via Wikipedia.

Glucose metabolism, via Wikipedia.

While practicing moderate nightly fasting and inter-meal fasting, Ivan has noticed several health benefits. His bloodwork has improved within the last year, he says, particularly with regards to his blood sugar control. ?My blood sugar levels have been lower overall, without dipping too low,? Ivan said. ?I?ve had better post-prandial [after eating] readings as well. I think another benefit is that while fasted, we aren?t bombarding our digestive tracts with copious amounts of foods frequently throughout the day.? As a caveat, Ivan says, it may be important to supply our guts with healthy amounts of fiber, especially when planning a long period of fasting or caloric restriction, to avoid colitis.

In the end, Ivan says, fasting is a ?play? on our body?s capability to adapt, for example to adapt to a lack of glucose availability and switch to a more metabolically efficient state while fasting, and to switch back upon refeeding. These adaptations can bring about benefits, but these benefits likely depend on the initial metabolic status of the individual, and how and when the refeeding happens. ?An overweight metabolically unhealthy person may benefit tremendously from fasting, whereas a normal weight metabolically healthy person may benefit as well, but perhaps not as much, since there?s not much for the body to ?detoxify,?? Ivan said.

Credit: Michael Stern, Flickr.com

Credit: Michael Stern, Flickr.com

There?s a huge need for more research on the impacts of intermittent fasting among healthy, active individuals. But whether you are metabolically healthy or unhealthy, moderate overnight fasting and inter-meal fasting is likely a safe place to start, along with a healthy diet and exercise. Longer fasts and fasting-mimicking diets may have other unique benefits, and caveats, but we will leave those for another blog post!

Want to learn more about intermittent fasting and how it may improve metabolic health and delay diseases of aging, in conjunction with exercise and diet? Get the LifeOmic LIFE Fasting Tracker app at https://lifefastingtracker.com/, or download it from the iOS App Store today!

The LIFE Fasting Tracker app guides you as you experiment with metabolic interventions for health.

Special thanks to Krishana Sankar, a PhD student at University of Toronto studying diabetes, for reviewing and fact-checking this blog post.