Introduction This is the first in a series of posts exploring artificial neural network (ANN) implementations. The purpose of the article is to help the reader to gain an intuition of the basic concepts prior to moving on to the algorithmic implementations that will follow.

No prior knowledge is assumed, although, in the interests of brevity, not all of the terminology is explained in the article. Instead hyperlinks are provided to Wikipedia and other sources where additional reading may be required.

This is a big topic. ANNs have a wide variety of applications and can be used for supervised, unsupervised, semi-supervised and reinforcement learning. That?s before you get into problem-specific architectures within those categories. But we have to start somewhere, so in order to narrow the scope, we?ll begin with the application of ANNs to a simple problem.

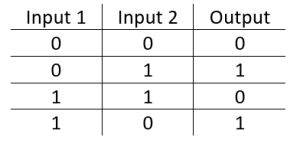

The XOr Problem The XOr, or ?exclusive or?, problem is a classic problem in ANN research. It is the problem of using a neural network to predict the outputs of XOr logic gates given two binary inputs. An XOr function should return a true value if the two inputs are not equal and a false value if they are equal. All possible inputs and predicted outputs are shown in figure 1.

XOr is a classification problem and one for which the expected outputs are known in advance. It is therefore appropriate to use a supervised learning approach.

On the surface, XOr appears to be a very simple problem, however, Minksy and Papert (1969) showed that this was a big problem for neural network architectures of the 1960s, known as perceptrons.

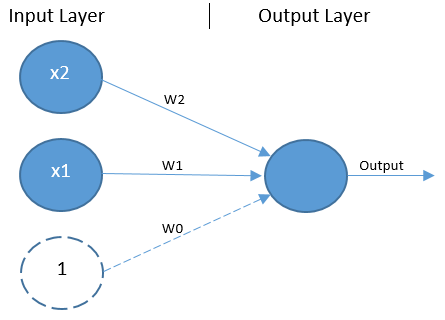

Perceptrons Like all ANNs, the perceptron is composed of a network of units, which are analagous to biological neurons. A unit can receive an input from other units. On doing so, it takes the sum of all values received and decides whether it is going to forward a signal on to other units to which it is connected. This is called activation. The activation function uses some means or other to reduce the sum of input values to a 1 or a 0 (or a value very close to a 1 or 0) in order to represent activation or lack thereof. Another form of unit, known as a bias unit, always activates, typically sending a hard coded 1 to all units to which it is connected.

Perceptrons include a single layer of input units ? including one bias unit ? and a single output unit (see figure 2). Here a bias unit is depicted by a dashed circle, while other units are shown as blue circles. There are two non-bias input units representing the two binary input values for XOr. Any number of input units can be included.

The perceptron is a type of feed-forward network, which means the process of generating an output ? known as forward propagation ? flows in one direction from the input layer to the output layer. There are no connections between units in the input layer. Instead, all units in the input layer are connected directly to the output unit.

A simplified explanation of the forward propagation process is that the input values X1 and X2, along with the bias value of 1, are multiplied by their respective weights W0..W2, and parsed to the output unit. The output unit takes the sum of those values and employs an activation function ? typically the Heavside step function ? to convert the resulting value to a 0 or 1, thus classifying the input values as 0 or 1.

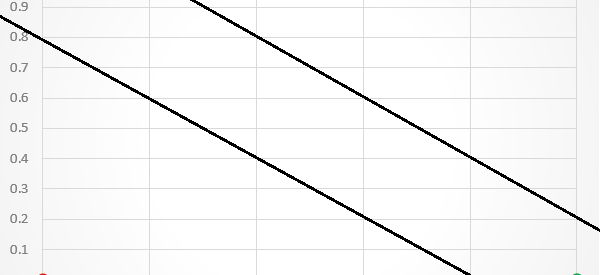

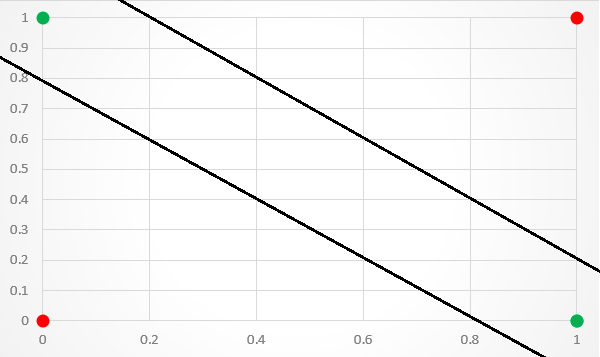

It is the setting of the weight variables that gives the network?s author control over the process of converting input values to an output value. It is the weights that determine where the classification line, the line that separates data points into classification groups, is drawn. If all data points on one side of a classification line are assigned the class of 0, all others are classified as 1.

A limitation of this architecture is that it is only capable of separating data points with a single line. This is unfortunate because the XOr inputs are not linearly separable. This is particularly visible if you plot the XOr input values to a graph. As shown in figure 3, there is no way to separate the 1 and 0 predictions with a single classification line.

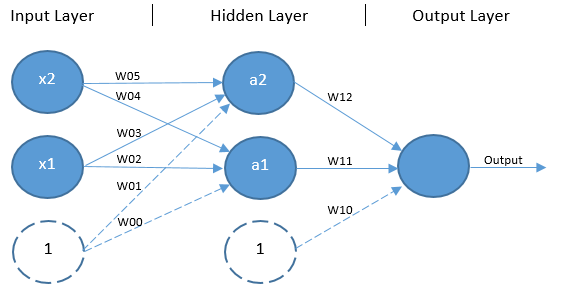

Multilayer Perceptrons The solution to this problem is to expand beyond the single-layer architecture by adding an additional layer of units without any direct access to the outside world, known as a hidden layer. This kind of architecture ? shown in Figure 4 ? is another feed-forward network known as a multilayer perceptron (MLP).

It is worth noting that an MLP can have any number of units in its input, hidden and output layers. There can also be any number of hidden layers. The architecture used here is designed specifically for the XOr problem.

Similar to the classic perceptron, forward propagation begins with the input values and bias unit from the input layer being multiplied by their respective weights, however, in this case there is a weight for each combination of input (including the input layer?s bias unit) and hidden unit (excluding the hidden layer?s bias unit). The products of the input layer values and their respective weights are parsed as input to the non-bias units in the hidden layer. Each non-bias hidden unit invokes an activation function ? usually the classic sigmoid function in the case of the XOr problem ? to squash the sum of their input values down to a value that falls between 0 and 1 (usually a value very close to either 0 or 1). The outputs of each hidden layer unit, including the bias unit, are then multiplied by another set of respective weights and parsed to an output unit. The output unit also parses the sum of its input values through an activation function ? again, the sigmoid function is appropriate here ? to return an output value falling between 0 and 1. This is the predicted output.

This architecture, while more complex than that of the classic perceptron network, is capable of achieving non-linear separation. Thus, with the right set of weight values, it can provide the necessary separation to accurately classify the XOr inputs.

Backpropagation The elephant in the room, of course, is how one might come up with a set of weight values that ensure the network produces the expected output. In practice, trying to find an acceptable set of weights for an MLP network manually would be an incredibly laborious task. In fact, it is NP-complete (Blum and Rivest, 1992). However, it is fortunately possible to learn a good set of weight values automatically through a process known as backpropagation. This was first demonstrated to work well for the XOr problem by Rumelhart et al. (1985).

The backpropagation algorithm begins by comparing the actual value output by the forward propagation process to the expected value and then moves backward through the network, slightly adjusting each of the weights in a direction that reduces the size of the error by a small degree. Both forward and back propagation are re-run thousands of times on each input combination until the network can accurately predict the expected output of the possible inputs using forward propagation.

For the xOr problem, 100% of possible data examples are available to use in the training process. We can therefore expect the trained network to be 100% accurate in its predictions and there is no need to be concerned with issues such as bias and variance in the resulting model.

Conclusion In this post, the classic ANN XOr problem was explored. The problem itself was described in detail, along with the fact that the inputs for XOr are not linearly separable into their correct classification categories. A non-linear solution ? involving an MLP architecture ? was explored at a high level, along with the forward propagation algorithm used to generate an output value from the network and the backpropagation algorithm, which is used to train the network.

The next post in this series will feature a Java implementation of the MLP architecture described here, including all of the components necessary to train the network to act as an XOr logic gate.

References Blum, A. Rivest, R. L. (1992). Training a 3-node neural network is NP-complete. Neural Networks, 5(1), 117?127.

Minsky, M. Papert, S. (1969). Perceptron: an introduction to computational geometry. The MIT Press, Cambridge, expanded edition, 19(88), 2.

Rumelhart, D. Hinton, G. Williams, R. (1985). Learning internal representations by error propagation (No. ICS-8506). California University San Diego LA Jolla Inst. for Cognitive Science.