Parents are rehoming their adopted children on the internet, just like pets. And it must stop.

What?s rehoming? It?s the practice of adopting children and then sending them back to the adoption agency ? or using sites like Facebook to find them a new home ? when they?re no longer wanted.

As a Rehoming 101 for public awareness, this ongoing series/investigative report aims to expose and end rehoming, using evidence-based research, historical and current analyses, and recent adoption commentary.

To see how this got started, review Dear White Woman Who Returned Her Adopted Kids and In response to those who support returning adopted kids, two open letters to those supporting this practice.

Don?t miss the next update! Follow me on Twitter and Facebook for series updates.

Part 1: The Exchange

It?s a sunny, humid summer afternoon in a city so crowded the heat waves rising from the cracked and patched sidewalks mingle with congested air. There are offices and row homes and cars and bikes, all the inanimate things competing for a role in city life.

Tucked away in a public hospital?s maternity ward, in a windowless room where the smell of bleach and sweat mingles with crisp recirculated air conditioning, a small woman reclines in a bed and cradles a stripe-capped newborn boy.

Around her, nurses bustle about. Scrub-clad women clean up afterbirth and spilled fluids, the evidence of every new mother?s ultimate physical sacrifice. A man in a smart gray business suit, inappropriate for the season, lurks beside the birthing bed with a practiced, timid smile.

Within three hours of holding her baby, the mother relinquishes her parental rights. To the lurking stranger, she hands over her sleeping child, who reassures the woman that her baby boy will be loved and given a secure future. A life better than she ? his mother ? could ever provide.

The child is placed with a waiting foster family, armed with gently used baby bottles, cloth diapers, and onesies. After many months, the child learns to sit up and crawl and eat solid food, embracing his foster family as his own, chained not to the legalities of kinship but to the security provided by his caregivers.

But on a day like any other, this baby ? almost a toddler by now ? is buckled into his car seat. While chewing on a purple teething ring and thinking nothing of his journey ahead, he rides along and falls asleep.

The child wakes up in the arms of an unfamiliar woman. Sensing her strangeness, he screams.

?He?s just fussy from the ride,? his foster mother says. ?He?s usually so good.?

The woman glances at her husband. She bounces the screeching toddler, talking over his high-pitched squeals. The quiet neighborhood, awash with cherry trees and lawns so professionally maintained their green nearly blinds, contrasts with the boy?s messy wails.

As the foster mother hands over the child?s small amount of possessions, she gives the baby boy a kiss, wishes the terrified child good luck, and drives away.

But luck wasn?t enough for this boy. As the weeks went by, his sleep-deprived parents grew more frustrated, unable to understand why the child didn?t respond to their coos, threw his carefully chosen toys at them, didn?t eat his food. He bit his adoptive father so hard he left a tiny ring-shaped bruise that lasted for weeks.

The parents reached out their social workers, the adoption agency, their lawyers.

?What?s wrong with this child?? they asked. ?What wasn?t disclosed to us about this baby??

On Facebook, the adoptive mother vented her worries to fellow adoptive parents.

?Maybe the mother was on drugs,? wrote one adoptive mother. ?These kids come from people who can?t even take care of themselves. It screws the kids up for us.?

?Just work harder!? said another mother. ?You can do it!!?

Still, days went by with no progress. By Christmas, the parents had enough. One mother shared a secret Facebook group dedicated to what would be unthinkable to most people: Rehoming, or returning their adopted kid.

?It?s a shame when this happens, but it?s not your fault,? said the parents. ?You can go through the agency but sometimes that takes forever. Try doing it privately.?

Another chimed in: ?The kid?s trauma is real but the social worker didn?t prep you for it. You can disrupt the adoption. It?s not working out.?

?We support you,? others wrote. ?Take care of yourself and your husband. Your marriage is more important.?

Several months later, the boy?s things ? some clothes, a stuffed turtle, a favorite book ? were packed into an elementary school child?s backpack, so small they barely filled the space. Around two o?clock on a winter afternoon, a sympathetic social worker arrived.

?I?m sorry this didn?t work out,? he said. ?But don?t worry. We?ll find another family soon. You tried.?

The child, now grown enough to recognize strangers, ran from the man and slammed his head into the wall.

?No go!? shouted the boy. ?No! No!?

The adoptive parents looked at the social worker and sighed, saying, ?The therapist said there?s nothing more we can do. He?s like this all the time.?

As the social worker carefully approached the boy, a hard plastic toy grazed his knee. Nonplussed, the large man tucked the flailing child under his arm and turned to the parents.

?We did our best. Sometimes it?s not enough. Thanks for trying. He?ll find a new family and be happy.?

And into the void went the boy once again, raging against a system he never knew had failed him. His birth mother, reassured her child would be loved, was unable to protect her son from an impermanency undeserved.

Part 2: The Research

Rehoming, though infrequent, happens more often than it should, but numbers are skewed since federal and state governments aren?t reporting this behavior. And yet it?s a very real issue underscoring adoption, still legal in the United States. While most parents do turn to agencies for help, others use social media and other private groups to swap both horror stories and their children.

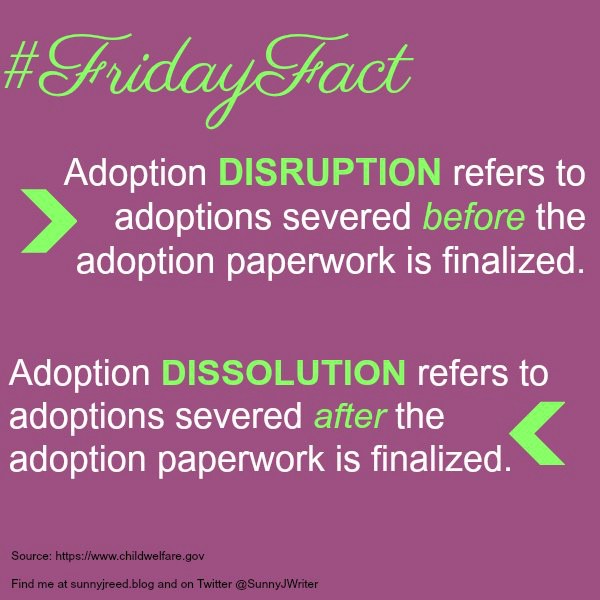

Officially, disruption is defined as returning children before the adoption?s finalization, while dissolution describes most rehoming victims? cases. In dissolution, the adoptive parents sever the relationship after completion of adoption paperwork.

But again, tracking disruptions and dissolutions is currently difficult, given the complex nature of child welfare and reporting discrepancies. What is known, however, is that more educated and affluent Americans tend to support dissolution. The reasons remain murky.

Dissolution and disruption aren?t new concerns, but it appears we still haven?t found a solution to the problem. In the late 1980s, researchers suggested that ?adoption disruptions apparently occur with less frequently than feared,? offering several reasons for an ? at the time ? decrease:

- Better parental screening on behalf of social workers

- ?Legal-risk? adoptions that don?t necessarily list official pre-adoption trial placements (thus reducing the ?disruption? statistic)

- Lack of time between the adoption and follow-up studies

The article cites a lower rate of disruptions in foster parent adoptions (6%), indicating that a preexisting relationship formed through fostering allowed the family time to get to know each other before finalizing placements. At the time of the study, transracial adoptions were no more likely to disrupt than same-race adoptions. And, the researchers pointed out, they didn?t ?know all of the effects that failed adoptions have on children.?

Though I?ve previously highlighted the parents? role in perpetuating this problem, much responsibility must be placed the adoption industry ? are adoption agencies truly equipped to serve the children, or simply suffer them more?

In future articles, I hope to dissect that question and will:

- Expose the agencies permitting rehoming

- Explain its causes

- Review literature offering suggestions for reducing dissolutions and disruptions

- Look at race and rehoming

- Suggest how you can help raise awareness.

In the meantime, catch up by:

- Watching Dan Rather?s Unwanted in America: The Shameful Side of International Adoption

- Reading this Reuters investigative report

- Taking a look at Ohio?s underground kid-trading network

- Following @StopRehoming for news and updates

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider sharing this article. Reform begins now.

Sunny J. Reed is a New Jersey-based writer. Her main body of work focuses on transracial adoption, race relations, and the American family. In addition to contributing to Intercountry Adoptee Voices, Plan A Magazine, and Dear Adoption, Sunny uses creative nonfiction as a way to reach a wider audience. Her first flash memoir (?the lucky ones?) was published in Tilde: A Literary Journal. Her second piece (?playground ghost?) is featured in Parhelion Literary Magazine. She is currently at work on a literary memoir. Follow Sunny on Twitter and Facebook.