?Digital blackface? dehumanizes Black people by flattening our stories

Credit: giphy.com

Credit: giphy.com

The internet is a portal to intercultural awareness. When discussing ramen versus pho, for example, all I have to do is pull out my phone and a quick Google search lets me know the noodle?s country of origin, the differences in their broths, and their evolution over time. Now I know what I?m talking about in future discussions about either, and I?m less likely to make potentially harmful assumptions around the cultures from which these foods come.

The internet is a portal to intercultural awareness. When discussing ramen versus pho, for example, all I have to do is pull out my phone and a quick Google search lets me know the noodle?s country of origin, the differences in their broths, and their evolution over time. Now I know what I?m talking about in future discussions about either, and I?m less likely to make potentially harmful assumptions around the cultures from which these foods come.

On the other hand, technology also makes it much easier to borrow elements of other cultures. When we all live behind the relatively anonymous wall of the internet, we have near-absolute power to display ourselves in whatever manner we like. I can pretend to be an Asian American man living in Wyoming if I want. (I?m not: I?m a Black woman living on the East Coast.)

One prominent problematic example of this is the use of digital blackface in GIFs. While using GIFs is not nearly as extreme as taking on a whole fake online identity, it represents a much more subversive way that cross-cultural blending from the internet can reinforce negative stereotypes and make us less empathetic when it comes to other races.

What is digital blackface?

Depending on whom you ask, digital blackface either refers to non-Black folks claiming Black identities online or to non-Black folks using Black people in GIFs or memes to convey their own thoughts or emotions.

Digital blackface takes its name from real-life blackface. The origins of this harmful tradition lie in mid-19th-century minstrel shows in which white performers darkened their faces and exaggerated their features in an attempt to look stereotypically ?Black? while mimicking enslaved Africans in shows performed for primarily white audiences. This trend of putting on Black appearances and acting out insulting stereotypes went a long way toward cementing the damaging white vs. Black narrative that much of the United States is built on.

Digital blackface, while less obviously and intentionally harmful than 19th-century blackface, bears many similarities in the way it reduces Black people to stereotypes and enables non-Black people to use these stereotypes for their own amusement.

Digital blackface in GIFs helps reinforce an insidious dehumanization of Black people by adding a visual component to the concept of the single story.

There is plenty of discussion on this topic, as the trend of non-Black people using often-exaggerated images of Black emotions or Black culture divorced from the original context to represent their own lives is not new. Ellen Jones in the Guardian wonders why reaction memes of Black people are becoming so popular online. Lauren Jackson in Teen Vogue lists a number of examples of Black folks in GIFs used for a wide range of emotional situations. Dr. Aaron Nyerges from the United States Studies Centre argues that the return of blackface in the digital era is a moment we should seize and use to avoid repeating the injustices of earlier years.

Everyone Can Learn From How Marginalized Communities Use Social Media

Why I think social media can be good for your mental health when you take cues from marginalized communities

onezero.medium.com

Technology is the vehicle that enables the rapid rise in this type of blackface. It allows for a faster and more widespread use of stereotypes in a more insidious and harder-to-fight manner than ever before. Digital blackface is frustrating and hurtful on an individual level. But to add injury to insult, digital blackface in GIFs helps reinforce an insidious dehumanization of Black people by adding a visual component to the concept of the single story.

GIFs help distill complex emotions or reactions into a single animated image. This reduction is common across the internet: Twitter encourages brevity in words with its 280-character limit, and Instagram?s focus on images means captions can be rendered entirely unnecessary if the user so desires. GIFs are useful when you?re making a face in person or feeling a specific emotion but aren?t quite sure how to translate it into text. They help ease the flat nature of words. Images are cross-cultural and often defy the bounds of language; all over the world sighted people process visual information in the same way.

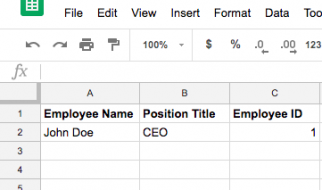

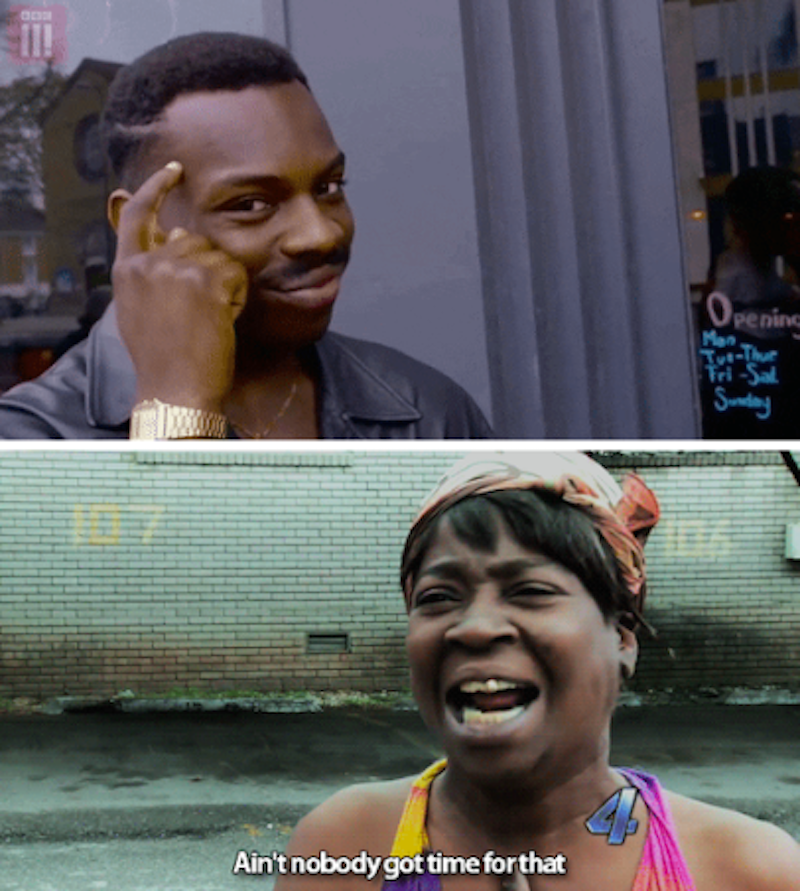

GIFs can be useful digital replacements for our expressions when we communicate online. But they can also reduce the people in the images into a single representation that blocks nuanced understandings of the groups those people come from. Popular GIFs representing Black people abound, from the ?think about it? reaction with a Black man tapping his head to the That?s So Raven nervous chewing gum GIF to the ?ain?t nobody got time for that? sensation that is Sweet Brown.

Chimamanda Adichie gave a compelling TED Talk in 2009 on the danger of a single story. She discusses how everyone from her white college roommate to herself (a Nigerian writer) was guilty of reducing those they don?t know to single stories based on incomplete narratives. As a child growing up, Adichie had a house boy (as is common in many Nigerian households). She had a mental image of him as being very poor, because that was all she had heard about his family. She was shocked to learn his family was also capable of making beautiful objects; she had simply never imagined another side to his life. The same was true for Adichie?s white college roommate. She had the single story of catastrophe attached to Africans as a whole, and was astounded to learn Adichie knew how to speak English and use a stove.

One danger of non-Black people popularizing funny GIFs of Black people is that these images become the single stories for those who don?t have other meaningful contact with Black folks. The exaggerated emotions often found in these GIFs become a form of entertainment, and the important contexts out of which they came are forgotten. Because of the rapid pace of technology, these single stories spread faster than ever before.

One problem with cross-cultural understanding is that if a person lives their life in a racially homogeneous region, they are unlikely to have significant interactions with someone of another race. If a white person has spent their entire life living in a white suburb, for example, the only experiences they may have had with Black folks might be with those who work in service positions in that suburb.

So is it not a good thing to have popularized images of Black folks, even if it does come in the form of digital blackface?

No. It?s not a good thing.

Having more flat representations of Black people in images and GIFs does nothing to improve cross-cultural understanding. In my experience, it actually decreases the likelihood that people will extend compassion to other racial groups. If the most common image a non-Black person has of a Black person presents that person as humorous and nothing else, anger on a Black person then becomes more extreme. Sadness becomes more extreme; even joy becomes more extreme. Having access to these portrayals may make a non-Black person feel as though they ?know? Black people, but using these in GIFs does nothing to actually increase anyone?s cultural understanding of Black folks.

If anything, the false sense of awareness a person may gain from using these types of representations harms their ability to sympathize in reality and hurts cross-cultural understanding overall.

Take Sweet Brown, for example. The ?ain?t nobody got time for that? GIF comes from an interview with a local news station she did directly after evacuating from her apartment complex when it caught fire. This GIF is used for everything from homework, to cooking, to any number of day-to-day complaints. These are typically a far cry from the experience of Sweet Brown herself. This GIF inserts humor into the traumatizing experience of a Black woman watching her home burn. Its popularity displays a stark lack of understanding of the reality of her situation. As she says in an interview with Oklahoma TV station KJRH, she wasn?t even trying to be funny.

But it?s not all bad. There are also ways technology is being used to increase empathy between different groups of people that can close the gap that digital blackface in GIFs has helped open. Video games are one of most obvious ways for technology to increase positive representations of racial diversity and help with increasing interracial empathy. My favorite games are those that help people step into cultures and experiences that are not their own.

The Dungeons and Dragons-like game Ehdrigohr is one such example. It?s a nontraditional fantasy world that represents the concept of the different pace of American Indian time and assumes there are no colonizers. Playing this game is a cooperative experience that can teach important lessons about the Native experience.

The Afropunk sci-fantasy setting of Swordsfall is another example. It?s a world of dark faces, in which gods live along humankind. The lore is made up of a world bible, World Anvil, a tabletop RPG coming in 2020, and upcoming novels. A structure like this, which will place RPG players in spaces where Black folks have advanced technology and exist in the beauty and power of a nation in which they are free and sovereign, inserts fundamental humanity back into technology?s representation of Black people.

Virtual reality is another vehicle used to create an entirely immersive artificial space. I am seeing many new ways to simulate experiences common to specific racial groups (like police treatment of Black folks) for other racial groups to experience and understand.

Technology takes away borders and closes distance in some beautiful ways, but there are spaces where it?s gone too far. The trend of blackface in GIF form is another way Black bodies are consumed by non-Black people in a harmful and stereotype-forming manner.

Digital blackface on its own doesn?t seem like a huge deal, but it is part of a much larger trend currently sweeping the United States that dehumanizes Black folks and allows for horrifying treatment in hospitals, police encounters, and even domestic spaces. While technology has the capacity to be a powerful agent for change in all of these spaces, we need to ensure the efforts are not being undercut by insidiously negative examples such as digital blackface.