This story contains racial slurs considered offensive and descriptions of historical racial bigotry.

A Utah-based chicken restaurant that thrived for almost three decades proved that in defiance of accepted contemporary convictions, institutionalized twentieth-century racial bigotry was not solely confined to the American Deep South.

While the American 1920s saw an increase in the use of typecast Blacks in popular culture, the decade also signified the dawn of automotive convenience, when roadside hotels and restaurants, and accompanying novelty architecture to draw in patrons, became common. And in Utah, then later in Washington State, a bizarre chain of roadside restaurants called the ?Coon Chicken Inn? combined the two.

These restaurants featured a 12-ft-tall grinning stereotype Black man?s head as the front door and proliferations of Black stereotypes inside, making it an identifying staple of racial bigotry in the American Pacific Northwest, where it thrived in the shadows of those more visible knuckle-dragging ?brutes? of the Deep South.

The derogatory significance of the Coon Chicken Inn (CCI) logo is rooted in a ?Coon? caricature that emerged in the 1830s. The term grew in early America as a shortening of ?raccoon? and soon became synonymous with ?a sly, knowing fellow.?

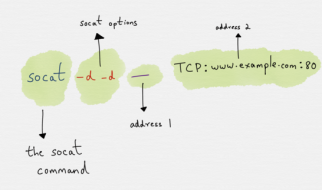

Menu cover

Menu cover

Another explanation of the term?s origin emerges from the transatlantic slave trade when captured Africans awaited loading onto slave ships were held in makeshift pens called ?barracoons? before their departures to North America, Brazil or the Caribbean

The transition of the use of ?Coon? into a derogatory term for an African-American, however, is connected to the introduction and instant success of a nineteenth-century minstrel show character named Zip Coon.

Unlike a similar character called Jim Crow, which represented an enslaved rural Black, Zip Coon represented a suburban free Black. Cultural historian and critic John Strausbaugh explains that Zip Coon became the first popular minstrel personality to represent the ?black urban dandy ? a ?negar? who ?acted white.?? For whites who feared job competition, Strausbaugh continues, Zip Coon served as a threat of ?the terror that lower-class whites had of being left at the bottom if ?niggars? like Zip got too uppity.?

On stage, blackface minstrel actors portrayed Zip Coon as a foolish and pompous windbag, provoking laughter that simultaneously reinforced white supremacy and open hostility toward African-Americans. Minstrel shows that proliferated throughout the American South until the early 1980s adopted Zip Coon?s persona through their ?Interlocuter? character ? a master of ceremonies who introduced acts and frequently delivered ?stump speeches? in mangled plantation dialect for comedic effect.

Minstrel shows were not confined to the Deep South ? they from 1910 to 1920 proliferated throughout the Northwest, including Utah, just before Maxon Lester Graham and his wife Adelaide founding the first Coon Chicken Inn in Salt Lake City in 1925. The opening coincided also with the proliferation of Blacks portrayed in American advertising never as business or cultural successes but only as servile dependents. Characters as Sambo, Jim Crow, Pickaninny and Jezebel along with the more highly visible Aunt Jemima and Uncle Tom were examples of Black stereotypes used to sell everything from soap to pancake mix, Cream of Wheat and chewing tobacco.

The Coon caricature also became synonymous with chickens and chicken thievery tales that emerged in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century narratives that were rooted in the fact that pre-emancipation slaves often did steal livestock from their owners, frequently as a form of protest or to supplement their paltry food rations.

Graham never publicly admitted what prompted him to use the Coon caricature as the marketing gimmick for his restaurant, but it seems the creation was an attempt to both capitalize on the massive popularity of those local minstrel shows as well as nostalgia for the well-worn stereotype of Blacks being chicken lovers, which proved marketable enough to attract those white travelers who saw the typecasting not as cruel but comedic. The message indirectly indicated that the chicken was high enough quality to appeal ?even to Coons.?

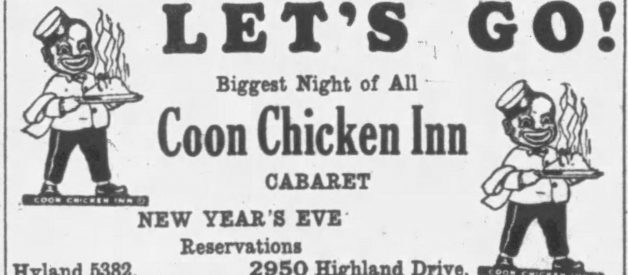

1931

1931

In the business

According to the Ferris State University?s Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, the Grahams got into the fried chicken business after spending several Sundays driving to a small town south of Salt Lake City to eat at a restaurant that served ?excellent chicken.?

Deciding that fried chicken would do well in suburban Salt Lake City, they opened their first CCI restaurant in the Sugar House suburb. For almost two years the restaurant grew in popularity, hosting parties, conferences and even lavish New Year?s Eve cabarets with their house band, the Coon Chicken Inn Orchestra.

In July of 1927, the restaurant was destroyed in a fire. In a highly publicized publicity stunt, Graham rebuilt a new CCI in 10 days. Three years later, two additional CCIs opened in Portland and Seattle. A fourth location later opened in Spokane.

For just under $1.00, guests could order a full multi-course meal, consisting of fruit or house salad, a shrimp cocktail, ?Southern fried Coon Chicken,? French fries, Parker House rolls, olives and pickles, even a slice of chocolate fudge cake and a beverage.

Menu interior

Menu interior

?Coon Chicken Inn is not just another restaurant,? announced a 1930 advertisement for the opening of the Seattle location, ?it is an innovation providing a pleasurable change from the ordinary caf ? a new eating place whose cuisine is considered in a class by itself, head and shoulders above the rest.? Indeed, the Inn was one of the first restaurants in the area to offer a drive-through and a delivery service.

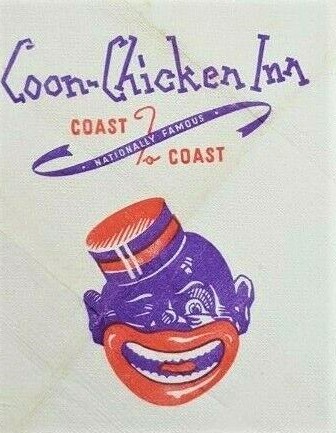

The Coon imagery did not stop at the front door ? Graham made a point to include it often and in as many places as possible. The notorious image of a stereotyped Black man with coal-black skin, a porter cap, huge red lips and oversize, brilliant white teeth doggedly appeared on postcards, in newspaper advertisements, matchboxes and on their delivery cars. Spare tire covers prominently featuring this logo were sold publicly, and could be spotted all over the city.

The Coon logo was heavily featured inside the restaurants as well. Menus, place mats, plates and flatware all fearlessly displayed the caricature. Even food items were not spared, with the menus featuring a ?Baby Coon Special? and even ?Coon Fried Steak.?

Protests

While there were never any vocal objections to the racist imagery at the Salt Lake City location, the opening of the Seattle location in 1930 drew the ire of the local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and Seattle?s African American newspaper, The Northwest Enterprise.

They both threatened Graham with a lawsuit alleging libel and defamation of race. The devious Graham was able to skirt both the NAACP and the lawsuit with ornamental window dressing ? he agreed only to remove the word ?Coon? from the delivery car and to repaint the giant head entrance to the restaurant from black to blue. He also agreed to cancel an order of 1,000 automobile spare tire covers. But the name of the restaurant remained as is.

Napkin image

Napkin image

The twelve-foot-tall, grinning blue Coon head erected on busy Bothell Highway was not only a slap in the face to local Blacks but served as a reminder to white Seattle natives of the twentieth-century Black migration to the Northwest which transformed the city?s racial demographics. In response to the migration, the city ? in a devious move straight from the Deep South playbook ? instituted restrictive racial covenants that prevented nonwhites from buying or renting homes in most Seattle neighborhoods. A 1930 Lake City covenant covering property near the CCI explicitly stated that:

?Said lot or lots shall not be sold, conveyed, or rented nor leased, in whole or in part, to any person not of the White race; nor shall any person not of the White race be permitted to occupy any portion of said lot or lots or of any building thereon, except a domestic servant actually employed by a White occupant of such building.?

The addition of the CCI imagery to these attitudes was more than enough to convey the Bothell area?s attitude towards Blacks, and certainly sent a clear message to all nonwhites as to who was and who was not welcome.

While the Portland and Seattle locations closed in 1949, the CCI in Salt Lake City unbelievably remained open until 1957. Artifacts of the Coon Chicken Inn are generally regarded today as Black Memorabilia collectibles ? a CCI placemat is for sale on eBay for $50, and an original napkin is selling for $400.00

***

Read more American Grotesk Historytelling at www.dalebrumfield.net.