Good morning! It?s December 30, 2018 ? or rather, day 7-Flower of ?trecena? 1-Jaguar in the solar year 7-Reed, which is also the fourth day of the ?veintena? or month Hu?yi T?z?ztli.

?Wait ? what??

It?s the ?Aztec? calendar(s), friends. Want to learn more?

Okay, basics first.

Most major Mesoamerican civilizations used TWO calendars simultaneously:

- a ritual calendar that was 260 days long, divided into 20 ?weeks? of 13 days, known by their Spanish name, trecenas

- a solar calendar of 365 days, 18 ?months? of 20 days each, known by their Spanish name, veintenas.

?That?s only 360 days, vato.?

Yeah, I know. Those five leftover days didn?t belong to any month. They just kind of lurked at the end of the year, bringing bad luck and chaos to people?s lives. More about them later.

Please note that the Nahuas (Toltecs and ?Aztecs,? etc.) ADOPTED this system. It had been in use for thousands of years before the first speakers of Nahuatl arrived in Central Mexico (in the 7th century CE or so).

The Mesoamerican calendar got its start in what is now Southern Mexico and Guatemala before the rise of Maya kingdoms. Evidence suggests the Olmecs developed it. The Maya calendar is perhaps the most famous and complex. They called the ritual year tzolk?in and the solar year haab?. The 5 Empty Days were known as wayeb?. The Maya also created what we call the Long Count, which allowed them to track time over millennia.

The Maya ritual calendar

The Maya ritual calendar

If you?re good at math, you?ll be able to see that once every 52 years, the ritual calendar (which the Nahuas called t?nalp?hualli or ?day count?) and solar calendar (xiuhp?hualli or ?year count?) align. The Nahuas marked this calendar round or Mesoamerican ?century? by the ?Binding of the Years? ceremony (xiuhmolp?lli).

Note that we JUST ended a bundle of years (52-year cycle) at the end of October, passing from year 6-Rabbit to 7-Reed. Were we living 500 years ago in Anahuac, we would have participated in an amazing ritual. The inhabitants of Central Mexico extinguished all fires, threw away their personal idols, and got rid of most of their household objects (in particular their metlatl, or mortar for grinding maize).

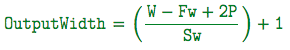

Meanwhile, the priests, dressed in the distinctive ornaments of the gods they served, set off for Mount Huixachtl?n (now called Cerro de la Estrella). There everyone would watch until midnight to ensure the stars continued their course. If they did, it was a sign that another calendar round could begin. A priest from the borough of Copolco would then spark a flame in the chest of a special sacrificial victim. The resulting New Fire was transmitted gradually, torch by torch, to the entire Valley of Mexico, in the midst of great rejoicing.

Priests like torches to take to every city.

Priests like torches to take to every city.

(For expert followers, I?m using the Caso correlation with Nicholson?s adjustments. Newbies, just note that there are three different systems for calculating the date had the Conquest never happened ? these may differ from what modern ?day keeper? shamans may affirm. For some indigenous people of Mexico, these calendars are still in use.)

Okay, now let?s dig in.

Ritual calendar first. The t?nalp?hualli consists of 20 sets of 13-day weeks. Every individual day has a name, a combination of a number (1?13) and one of 20 day signs. This means that each ritual year, all possible combinations of number and sign cycle through.

Those signs (in English, in order) were crocodile, wind, house, lizard, snake, death, deer, rabbit, water, dog, monkey, grass, reed, jaguar, eagle, vulture, earthquake, flint, rain, and flower.

The Aztec day signs.

The Aztec day signs.

Days were named by combining the number of the week with the next sign on the list. According to Nahua religion, the very first day in the universe was 1-Crocodile, as crocodile is the first day sign. The following days were 2-Wind, 3-House, 4-Lizard, and so on, all the way to 13-Reed, after which the NEXT ?trecena? started with 1-Jaguar, 2-Eagle, etc.

See?

The resulting 20 trecenas were named for their first day (1-Crocodile, 1-Jaguar, 1-Deer ? all the way to 1-Rabbit, last trecena of the solar year).

These days were vital for divination. Books called t?nal?matl helped priests predict the fate of babies born or baptized that day.

For example, I was born February 27, 1970. That?s 5-Wind of trecena 1-Flint in year 10-Rabbit of the last year bundle. Here?s what a priest or midwife might have told my parents:

?Wind days are governed by Quetzalcoatl as provider of t?nalli (the shadow soul or life energy that comes from the sun). 5-Wind is a bad day for teamwork. Its influences are inconstant and vain. It is a good day, however, to root out bad habits.?

Had I been a Nahua baby, the midwife might have suggested I be baptized several days later, on a date with a more auspicious sign, to counterbalance this. (Yes, the Nahuas baptized their children, too, long before the Spanish came).

Trecenas also have gods associated with them. Mictlanteuctli (god of the Underworld) rules over the Flint trecena of my birth. Again, my parents might have been told, ?Your son?s trecena signifies an ordeal or trial that pushes one to the very edge of endurance. It forebodes an abrupt change in the continuity of things. These are good days to shed old skins; bad days to cling to what is already known.?

(Quotes adapted from https://www.azteccalendar.com/)

That was the RITUAL calendar. Now for the SOLAR.

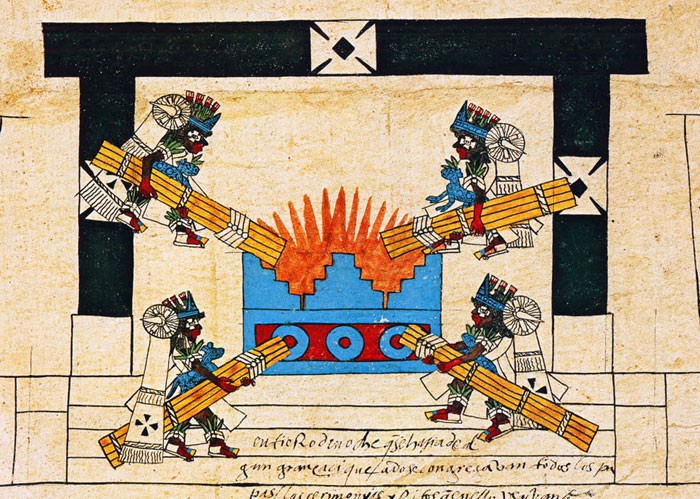

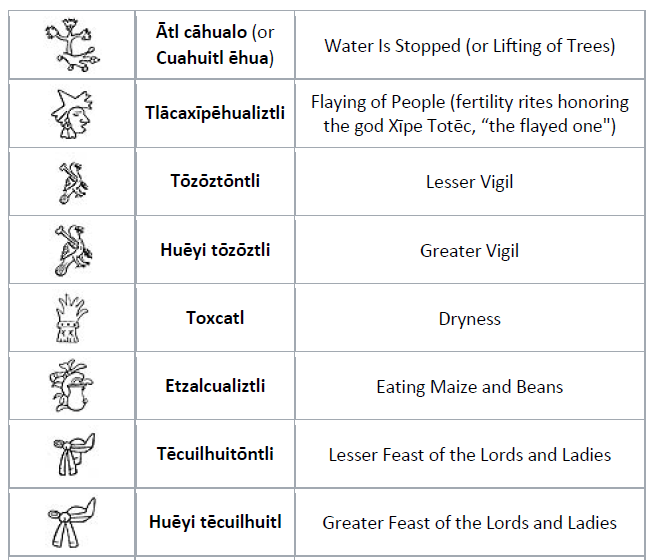

The xiuhp?hualli had 18 months of 20 days (so it wasn?t ?lunar? as some call it). We don?t know the Nahuatl name for month (?m?tztli? or ?moon? appears to be a colonial neologism), so they are commonly called veintenas. Each month had a name, though, and attendant rituals.

Except for those last five days. The Nahuas called them ?n?mont?mi? (?full of nothing? or Empty Days). They were bad luck.

If you were born during that disastrous time, they named you Nemo. ?

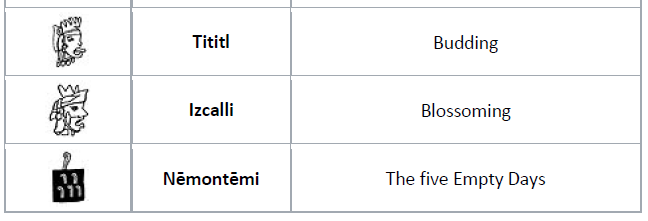

Here?s a chart with the glyph for each month, its name in Nahuatl, and an English gloss.

Now originally these months matched up with seasonal changes and so forth, but as far as we know, there were no leap years, so those correspondences have become unaligned 500 years after the Conquest. Perhaps the Nahuas would have devised a way to course-correct. It?s been suggested that after every calendar round, an additional trecena was added to the following year, but the evidence for this addition is sketchy.

The last day of the last month of the year gives its ritual name to the solar year. The final day of month 18 for this past solar Mesoamerican year was 10/19/18 or 13-Rabbit. As a result, it was a rabbit year (6-Rabbit, to be precise). The solar year we?re in (7-Reed) will have the final day of its last month on 1-Reed (10/19/19).

If you?re good at math, you?ll see that only four day signs can give their names to the solar year. These ?bearers? are House, Rabbit, Reed, and Flint. The number that accompanies the name is raised +1 every year, and then the numbers reset after 13.

That means, after the Empty Days are over this solar year, a new one will begin on 10/25/19, which is ? Can you guess it? We?re in 7-Reed, so it?ll be ?

8-Flint.

Followed by 9-House, 10-Rabbit, 11-Reed, 12-Flint and 13-House.

Then back to 1-Rabbit.

Make sense?

Yeah, I know. It was hard for me as well the first time someone explained it.

The indigenous people of Mesoamerica were brilliant.

But keep studying. You?ll catch up with them one day.

Not the Aztec calendar, but the Aztec sun stone (which does have the day signs in a ring, however).

Not the Aztec calendar, but the Aztec sun stone (which does have the day signs in a ring, however).