Mean Absolute Error versus Root Mean Squared Error

Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root mean squared error (RMSE) are two of the most common metrics used to measure accuracy for continuous variables. Not sure if I?m imagining it but I think there used to be a time when there were a lot more published MAE results. It seems that publications I come across now mostly use either RMSE or some version of R-squared.

Is RMSE actually better in most cases? When would it be better to use MAE? I wanted to dig into these two questions a bit because I find myself using RMSE often because it?s been programmed as the default modeling metric.

Definitions

Mean Absolute Error (MAE): MAE measures the average magnitude of the errors in a set of predictions, without considering their direction. It?s the average over the test sample of the absolute differences between prediction and actual observation where all individual differences have equal weight.

If the absolute value is not taken (the signs of the errors are not removed), the average error becomes the Mean Bias Error (MBE) and is usually intended to measure average model bias. MBE can convey useful information, but should be interpreted cautiously because positive and negative errors will cancel out.

Root mean squared error (RMSE): RMSE is a quadratic scoring rule that also measures the average magnitude of the error. It?s the square root of the average of squared differences between prediction and actual observation.

Comparison

Similarities: Both MAE and RMSE express average model prediction error in units of the variable of interest. Both metrics can range from 0 to ? and are indifferent to the direction of errors. They are negatively-oriented scores, which means lower values are better.

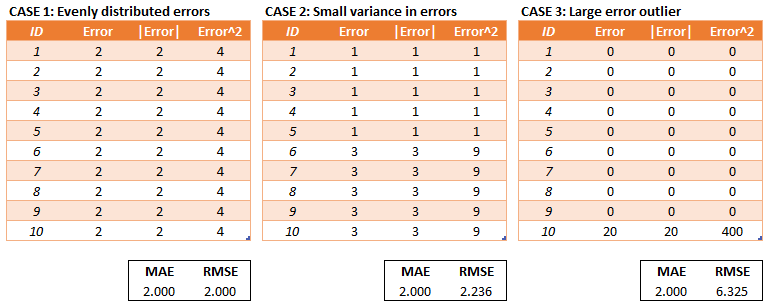

Differences: Taking the square root of the average squared errors has some interesting implications for RMSE. Since the errors are squared before they are averaged, the RMSE gives a relatively high weight to large errors. This means the RMSE should be more useful when large errors are particularly undesirable. The three tables below show examples where MAE is steady and RMSE increases as the variance associated with the frequency distribution of error magnitudes also increases.

MAE and RMSE for cases of increasing error variance

MAE and RMSE for cases of increasing error variance

The last sentence is a little bit of a mouthful but I think is often incorrectly interpreted and important to highlight.

RMSE does not necessarily increase with the variance of the errors. RMSE increases with the variance of the frequency distribution of error magnitudes.

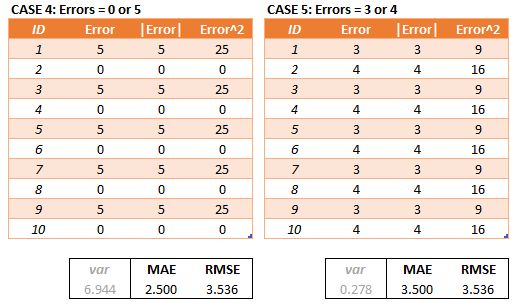

To demonstrate, consider Case 4 and Case 5 in the tables below. Case 4 has an equal number of test errors of 0 and 5 and Case 5 has an equal number of test errors of 3 and 4. The variance of the errors is greater in Case 4 but the RMSE is the same for Case 4 and Case 5.

3,4,5 is a Pythagorean Triple

3,4,5 is a Pythagorean Triple

There may be cases where the variance of the frequency distribution of error magnitudes (still a mouthful) is of interest but in most cases (that I can think of) the variance of the errors is of more interest.

Another implication of the RMSE formula that is not often discussed has to do with sample size. Using MAE, we can put a lower and upper bound on RMSE.

- [MAE] ? [RMSE]. The RMSE result will always be larger or equal to the MAE. If all of the errors have the same magnitude, then RMSE=MAE.

- [RMSE] ? [MAE * sqrt(n)], where n is the number of test samples. The difference between RMSE and MAE is greatest when all of the prediction error comes from a single test sample. The squared error then equals to [MAE^2 * n] for that single test sample and 0 for all other samples. Taking the square root, RMSE then equals to [MAE * sqrt(n)].

Focusing on the upper bound, this means that RMSE has a tendency to be increasingly larger than MAE as the test sample size increases.

This can problematic when comparing RMSE results calculated on different sized test samples, which is frequently the case in real world modeling.

Conclusion

RMSE has the benefit of penalizing large errors more so can be more appropriate in some cases, for example, if being off by 10 is more than twice as bad as being off by 5. But if being off by 10 is just twice as bad as being off by 5, then MAE is more appropriate.

From an interpretation standpoint, MAE is clearly the winner. RMSE does not describe average error alone and has other implications that are more difficult to tease out and understand.

On the other hand, one distinct advantage of RMSE over MAE is that RMSE avoids the use of taking the absolute value, which is undesirable in many mathematical calculations (not discussed in this article, another time?).