Imagine a serial killer, say, Ted Bundy, he is charming, fit, good looking, some say attractive. People trusted him, so much so that he was able to convince many victims to go along with him wherever he wanted to take them. Many of Ted Bundy?s traits could be reasonably called virtues ? at least in the Aristotelian sense. Aristotle said that virtues were character traits that were in the middle between two extremes. Some of the virtues he identified were things like courage, ambition, modesty, friendship. A guy like Ted Bundy could have all these, but yet no one would say he was a good person.

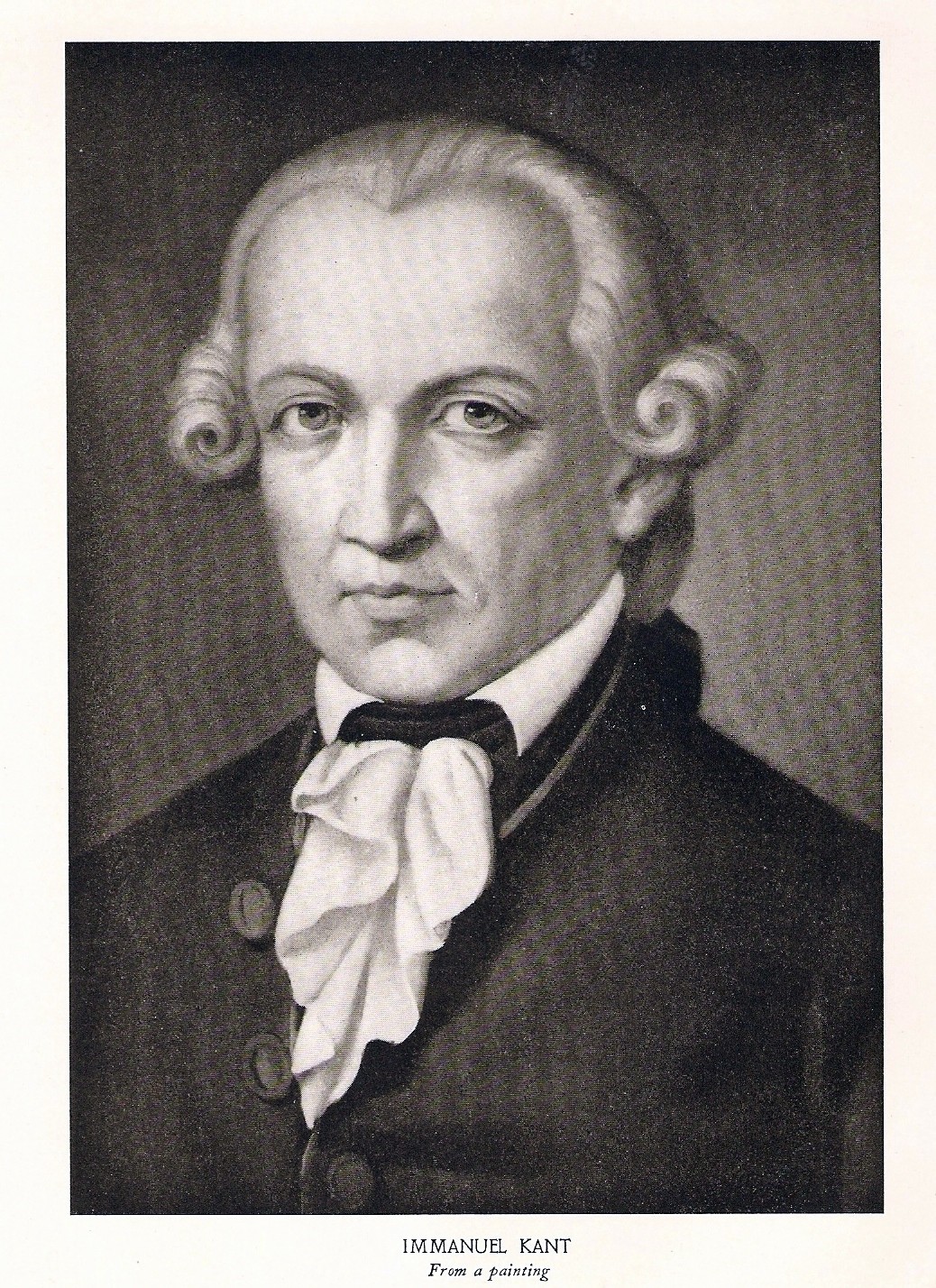

The philosopher Immanuel Kant argued that when it comes to morality, simple virtues will not do. Courage, intelligence, wealth etc. can be used for good or for evil. For this reason, the virtues praised by the Greeks were not a satisfactory way to distinguish good and bad. They are nice traits to have, but they are not enough. For Kant, what makes an action moral is purely in the intention with which the action is made. If I give a homeless person a dollar because I want to help them, my action is good. If I give them a dollar because they are making a weird noise and I want them to shut up, the action is not good. A good action, Kant says, is one where you do it with the intention of doing a good thing (he also called it the good will, we will define this and other Kantian next).

Kant?s Ethical Concepts.

Kant is a difficult author to read, he was the first philosopher to write in german, even Leibniz wrote in Latin and French, therefore he did not have the vocabulary for the things he wanted to say available to him. Most of his terms have a very specific definition that is often different from the way we use the words in English. In order to understand Kantian Ethics, we need to understand his fundamental concepts.

Good Will: For Kant, the only thing that is always good in itself is a good will. (Wishing to do the right thing). We should want to act in a certain way because it is right, not because of the consequences. A good will can exist even if nothing is actually done, if someone is paralyzed for instance, they can still be good if they have good will. Our job as moral agents is to work out what our duties are, and then to follow them in good will.

Duty: For Kant ?duty? means something different than what we usually think it means. Usually doing something because it?s your duty means following certain external rules or orders. Kant did not mean that at all. Doing something from duty is the right way to act only when that duty is towards you own internal moral law that you have figured out by careful thinking and logic. Some people are naturally nicer than others, but Kant thought we should not trust our natural inclinations as motivations for actions because they were unreliable and passive. If we take the time to figure out what the moral laws are (see later the categorical imperative), then we can follow the law from duty in a way that is reliable, consistent and immutable.

Universality: Kant thought that the main characteristic of moral principles is that we think they are ?universable? so to speak. If we think that something is right, we think that everyone should do it (at least if they are in a similar situation, although he thought there were principles that were valid independent of the situation). When I say, thou shall not kill, I am saying it is wrong to kill and no one should kill. If I say that it is ok to kill in self-defense I am saying that it is ok for everyone to kill in self-defense. Claims of right and wrong have this characteristic of universality. Moral law is by its nature universal for Kant.

Maxims: Maxims are rules that guide our actions. For instance, I can have as a rule ?Never lie to your friends? or ?Always respect your parents? or ?Always look out for yourself first? or ?Never break a promise.? These are maxims we use when we think we are acting morally. For Kant an action is right depending on the maxim that motivates it. In order to know if they are the maxim that motivates an action is a good maxim, we need to know if they can become a moral universal law, we need to put them through a test. The test to know if a moral maxim is a universal moral law is very simple: a maxim that can be universalized without contradiction is a universally good maxim (we will see what he means more clearly in the section about the hypothetical imperative).

Hypothetical Imperatives: These types of imperatives are ?If? then statements?. Kant says they are about prudence rather than morality. Examples of these would be: ?If you want money, you should get a job.? or ?If you want a good grade, you should study.? These are not moral universal laws.

Categorical Imperative: This is the crux of Kant?s ethics. A categorical imperative is something you must follow independent of your inclinations, of the consequences, of whatever else. A maxim is a universal law if it is a categorical imperative. He defines a categorical imperative in three ways, but the most well know if:

Act only according to that maxim which you can at the same time will that it should become a Universal Law.

What this means is that when I am considering if an action is right or wrong I have to think, if everyone did this action that I am now doing, what would happen? For example, if I am thinking of breaking a promise if everyone broke promises when they think it is a good idea, what would happen? In a world where people did that promises would lose their meaning and would no longer be believed, the concept itself would collapse. Kant thinks that all truly moral concepts are the same in this respect, it would be illogical to do something that goes against the moral law.

This may be a little difficult to grasp, but watch this video from the philosopher Todd May who worked with the writers of The Good Place:

The categorical imperative actually has three formulations, the first one is the one we mentioned above:

1st: Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.

2nd: Act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never merely as a means to an end, but always at the same time as an end.

3rd: Thus the third practical principle follows [from the first two] as the ultimate condition of their harmony with practical reason: the idea of the will of every rational being as a universally legislating will.

The first formulation is the most well know one and we already talked about it.

The second states that we can never use a person as a means, that each person is an end in itself. Using someone purely as a means, or as a mere means, is to use someone in a way that they would not in principle consent if they knew what you were doing. We have to assume that each person has maxims of their own that need to be respected. We can?t trick them and make them break their own maxims unknowingly. We can?t coerce them either, as that would be forcing them to your will, not theirs. When we lie and break promises what is in fact happening is that people are made to act in ways they would not have acted if they knew the truth, therefore, when you lie to others you are robbing them of their moral agency.

The third formulation says that every rational human being is a universally legislating will. What he means here is that we each need to figure out the moral law for ourselves using reason. If we use reason, and because logic is universal, we will come up with the same categorical imperatives. But we each must be free to explore these and come to our conclusions. Remember acting from duty? That means acting from duty to the universal law that you have figured out yourself by using reason.

Here is a video I think explains these three formulations very well:

Kant?s Axe:

This is an example that Kant came up with himself, and it is probably the harshest example against his theory that anyone could think of. One of the actions that went against the categorical imperative was lying. According to the categorical imperative, in order to know if it is ok to lie we need to know what would happen if everyone lied when they thought it was convenient for them. If everyone lied, then no one would believe anyone else and therefore there would be no purpose in telling a lie. People lie because that will give them some sort of advantage, but everyone lied, then it would not give them any advantage, the concept of lying would collapse. Therefore we should not lie, ever.

Kant then comes up with this example, called Kant?s Axe as something that could challenge his theory:

According to Kant, even in this extreme case, you should not lie to the axe murderer. Do not lie is a categorical imperative. If we think about it carefully, if we lie to the murderer and he has never murdered anyone, he may leave, but we have taken away his ability to make a moral choice. If the murderer walks in and is attacking our friend, we can do something to stop him in self-defense, he has already made his moral choice and now we can stop him. But if we lie to him we are taking away his right to be a universally legislating will. Kant bites the bullet in this example and says: you should not lie. If you don?t lie you don?t break your universal moral law and you are not doing anything wrong, according to him.

What do you think? Please let me know in the comments.