Amorphous and puzzling paintings that gain meaning in the looking

Water Lily Pond (1917?19), by Claude Monet. Source Wiki Art

Water Lily Pond (1917?19), by Claude Monet. Source Wiki Art

When standing in front of a water lily painting by Claude Monet, you have the sense that a moment of magic is about to take place. Here is a painting that is many feet wide and six feet high, an expanse of misty, vibrating colour that fills your field of vision.

Somewhere in the meeting place between your eyes and the picture surface, a discovery is taking place. The magic of these pictures ? and why they are so beguiling too ? is that the encounter unfolds, repeats, returns and spirals like a piece of music.

Claude Monet produced around 250 paintings based on the water lilies that were growing on the pond at his home in Giverny, a town in northern France where the artist lived for the last 40 years of his life.

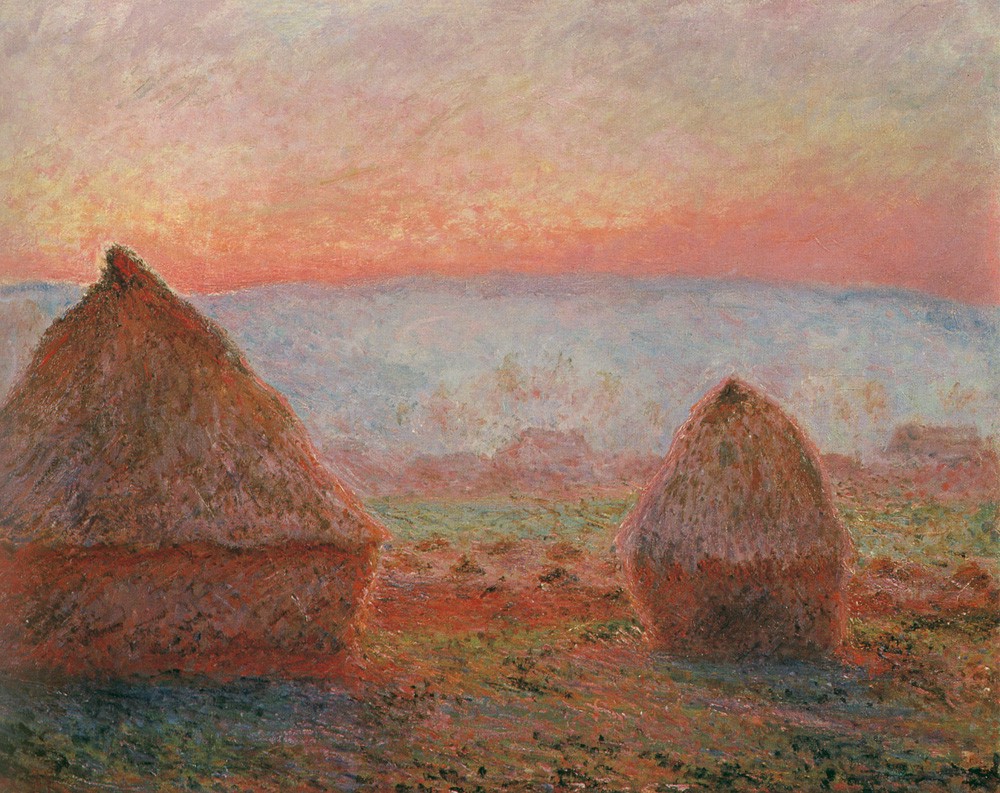

Haystacks at Giverny, the Evening Sun (1888), by Claude Monet. Source Wiki Art

Haystacks at Giverny, the Evening Sun (1888), by Claude Monet. Source Wiki Art

Monet had long appreciated the value of working in ?series?. His practice of painting the same subject again and again had yielded one of the great achievements of Impressionist art: that the fleeting effects of light and changing weather conditions could be registered as an aesthetic insight. To compare and contrast the series of paintings Monet made of Haystacks, for instance, is to explore the transient nature of light, and to witness how the painted effects might utilise an extraordinary breadth of colour and texture.

The water lily paintings comprise the largest of all of Monet?s series projects. He painted them from around 1897 until his death in 1926. He used his gardens as the subject matter, and the paintings he made there occupied the artist with growing intensity as he aged.

The first point of interest in the water lily works is that there is typically no horizon to the landscape. Nor any sense of scale. We rarely see the pond?s edge. Monet?s vantage point is looking down into the water, whose surface is made up of two principle elements: the reflections of the sky and the water lily plants themselves. The effect of this manner of composition is to offer a swathe of enigmatic reflections broken up with more definite ?events? of the water lilies. The picture plane is scattered with episodes of more and less intensity, made with brushmarks of various grades of precision and looseness.

Water Lily Pond (1917), by Claude Monet. Source Wiki Art

Water Lily Pond (1917), by Claude Monet. Source Wiki Art

Given the surreal, abstract nature of the composition, as a viewer your eyes tend to roam the canvas, left and right, up and down, looking for a place to settle and anchor, wondering where the form you are focusing on quite begins and ends, and how exactly it is constructed.

When seen up close, the paint is daubed in slack, crumbling brushmarks, many of them so loose and hovering that they blend like the meeting of tonal mists. Colours overlay one another to create a shimmer of uncertain sheets. The waterlilies themselves are fashioned from simple elliptical strokes, mainly in lemon yellows and pale greens, a spot of red here and lilac there, with a vague underpinning of blue to suggest shadow.

Little else is apparent in any figurative sense. The remaining space ? most of the canvas ? is made up from a gentle building up of dry-brush paint marks: orange and feint green upon pinks and purples, upon blue and red and orange.

Monet created a large studio at Giverny for the express purpose of making his water lily paintings. His earlier versions of water lilies are more precise in their draftsmanship, made on a scale that tends to be smaller and more compact.

An early painting of ?Water lillies? (1897?1899) by Claude Monet. Source Wiki Art

An early painting of ?Water lillies? (1897?1899) by Claude Monet. Source Wiki Art

As he explored the subject in greater depth, the paintings took on a more expansive scale. After an accident in 1901, which caused temporary loss of sight in one eye, Monet suffered increasingly from deterioration of his sight. The impact on his painting was in the steady abandonment of details in preference for a more nebulous effect of near-abstract panoramas.

Monet?s gradual loss of sight was a source of episodic unhappiness. He underwent fits of despondency from which he had to rouse himself with gritted determination. Nonetheless, his artistic rate of work did not diminish; in fact Monet began work on some of the most ambitious canvases he ever made.

In 1922, aged 82, Monet signed a contract donating a series of large water lily canvases to the French government, to be housed in redesigned rooms at the Orangerie museum in the centre of Paris. Monet?s wish was that the display should make use of natural light, plain walls and sparse interior decoration. There are eight paintings on display at the Orangerie, hung in two oval rooms all along the walls. The effect of the oval shaped rooms is to surround the viewer from all sides with curving panoramic works, each of which measures around 37 feet across.

One of two rooms in the Muse de l?Orangerie containing some of Monet?s Water Lilies. Source Wikimedia Commons

One of two rooms in the Muse de l?Orangerie containing some of Monet?s Water Lilies. Source Wikimedia Commons

The Orangerie works are a culmination of a series of paintings that were three decades in the making. As a permanent memorial to the Impressionist artist, the collection is well worth visiting when making a trip through Paris.

Would you like to get?

A free guide to the Essential Styles in Western Art History, plus updates and exclusive news about me and my writing? Download here.

Christopher P Jones is a writer and artist. He blogs about culture, art and life at his website