They were part of the original fight club. An underground fighting gang from the 1800s and early 1900s.

Hitler?s favorite Nazi commando, who famously rescued Mussolini from an Italian hilltop fortress. ? Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=80725646

Hitler?s favorite Nazi commando, who famously rescued Mussolini from an Italian hilltop fortress. ? Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=80725646

For those who enjoy watching a good World War Two movie involving the struggle against Nazi Germany, they have undoubtedly seen an SS officer wearing his all black uniform, swastika armband, leather coat and sporting a large facial scar on the left cheek. Some viewers might think this svelte, spit-polish epitome of military rigor they are watching on screen is showing a deep facial scar only as a Hollywood prop. In essence, a ruse to make the actor look tough and ruthless. However, the truth is facial scars were extremely common among Austrian and German soldiers going back to World War One.

Ernst Julius Gnther Rhm 28 November 1887?1 July 1934) was a German military officer and an early member of the Nazi Party .https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12685396

Ernst Julius Gnther Rhm 28 November 1887?1 July 1934) was a German military officer and an early member of the Nazi Party .https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12685396

They are called dueling scars or Schmisse in German and were seen as a badge of honor since as early as 1825. Alternatively referred to as ?Mensur scars?, (academic fencing scars), ?smite?, ?Schimitte? or ?Renommierschmiss? they were popular among upper-class Austrians and Germans (to some lesser extent in some Central European countries) involved in academic fencing at the start of the 20th century. Consequently, many of these same upper-class men who fashioned these dueling scars found themselves wearing German army uniforms in both World War One and Two.

Korbschlger ? hoeglund.org

Korbschlger ? hoeglund.org Glockenschlger ? Imgur

Glockenschlger ? Imgur

During this period of time and even today, academic fencing is different from how the sport is generally currently practiced. Today, fencing uses specially developed swords and gear that minimize injuries. The ?Mensurschlger? (mensur sword or hitter) used in these bouts are instead quite deadly. They are made in two versions: the Korbschlger with a basket-type guard and the Glockenschlger equipped with a bell-shaped guard. Both exhibiting sharp edges and tips able to slash through flesh or pierce a victim?s body causing death.

Source Pinterest

Source Pinterest

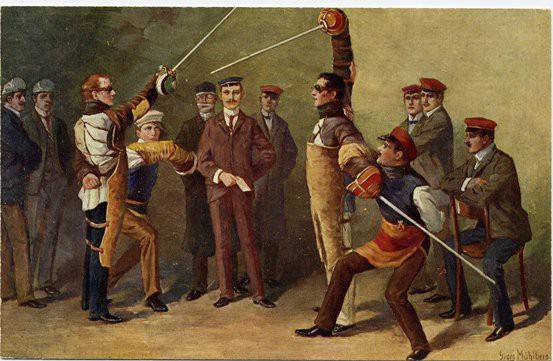

In the past, individual duels between students, known as Mensuren, were somewhat ritualized. Protective gear was often worn which included padding on the arms, chest, throat and an eye guard. Although, in many cases duels would emerge spontaneously, in which case protective gear would be minimal.

During the 19th and 20th century, these duels between students were considered an honorable distinction among fraternity members, as taking a blow to the face showed courage and was a lasting reminder of the fraternal bond.

Source Pinterest

Source Pinterest

German military laws permitted men to wage duels of honor until shortly after World War I. During the Third Reich (January 1933 to May 1945) the Mensur was prohibited at all universities. The Nazi state had recognized that academic fencing was an integral part of the independently-minded Studentenverbindung or fraternities which still existed during the 1930s. The Nazis also viewed these fraternities to be representative of the previous government and wanted to disband them.

by joerookery on flickr

by joerookery on flickr Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=940450

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=940450

With Nazi pressure increasing, fraternities were forced to officially suspend their activities, however underground comradeships were founded. These illicit organizations provided the means for organizing and practicing Mensur bouts among the former fraternities while remaining undetected by the Nazi secret police. After the war, many of these fraternities were reactivated and resumed the Mensur fencing tradition.

These duels were seen as an ideal way to show courage by being able to take a blow. This was in fact more desirable that inflicting the wound. While it was important to show one?s dueling ability, it was also as important to be capable of taking the wound inflicted by the opponent.

Since World War Two Mensur?s popularity has declined substantially. It is only practiced in some 300 traditional fraternities in Germany, Poland and a few other European countries.

Today, academic fencing is neither a duel nor a sport. It is a traditional way of training as well as developing character and personality. In a Mensur bout, the participants are protected by steel meshing armor called chainmail. They additionally wear padding for the body, arms, fencing hand and throat, completed by steel goggles with a nose guard.

The fencers stand at arm?s length and remain in one place. The goal is to hit the unprotected areas of their opponent?s face and head. Flinching or dodging is not allowed. The goal is still the same as in the past; to endure a blow stoically. Two physicians are always present (one for each opponent) to attend to injuries and stop the fight if necessary.

- Mensur Video. This video shows how a Mensur duel is carried out.

Social Significance

Within the elite social context of the time, gaining these scars was associated with status and the prestigious academic institutions in which these duels took place. The scars showed courage as well as being ?good husband material.? Even Otto von Bismarck, Chancellor of the German Empire prior to the Third Reich, once said that a man?s bravery and courage could be judged ?by the number of scars on their cheeks.?

Minority groups in Germany also viewed the practice of facial scarification as a way to aid their social situation. This included some Jews who were said to have worn their scars with pride and were even perceived by others as being ?socially healthy individuals.?

Nature of the Scars

Since most Mensur duelists were right-handed, the scars they exacted on their opponents were mostly on the left side of their heads and faces. Hence, the right profile seemed mostly untouched. Experienced fencers, who had fought many bouts, often accumulated a multitude of scars. In a New York Times article of March 18, 1877 titled Dueling in Germany.; The Bane of the Universities Burial of a Student Victim to the Brutal Practice reports on a duelist who died in 1877 and who had at least thirteen duels sporting ?137 scars on head, face and neck?.

In an article by the St. Louis Globe of August 15, 1887 titled Scarred Dueling Heroes, reported the scars not to be of a serious nature. It partly read:

?wounds causing, as a rule, but temporary inconvenience and leaving in their traces a perpetual witness of a fight well fought. The hurts, save when inflicted in the nose, lip or ear, are not even necessarily painful, and unless the injured man indulges too freely in drink, causing them to swell and get red, very bad scars can be avoided. The swords used are so razor-like that they cut without bruising, so that the lips of the wounds can be closely pressed, leaving no great disfigurement, such, for examples, as is brought about by the loss of an ear.?

The adoration of these facial scars prompted many students who did not practice fencing to scar themselves with razors in imitation. Some would pull on their scabs in order to exacerbate the scars. In other cases, students paid doctors to slice their cheeks.

As BMEzine Enclypodia reports in one of its pages titled Dueling Scars:

?Students too afraid to actually duel would cut themselves with razors or contract doctors to form the wounds, and then would repeatedly tear open the wound to irritate them, as well as using salt, wine, and even sewing horse hair into them to ensure a prominently keloided scar.?

The custom of obtaining dueling scars, however, began to die off shortly after the Second World War.

Today, the fencing fraternities that still exist are in Germany, Austria Switzerland and a few other European countries. Their tradition, besides academic fencing, also include dueling scars, although their fervor for facial scarification does not reach the fever pitch as in earlier times.