The removal of racist songs from school music programs is long overdue

Title page for ?I?ve Been Working on the Railroad? in Beatrice Landeck?s ?Songs to Grow On? (1950).

Title page for ?I?ve Been Working on the Railroad? in Beatrice Landeck?s ?Songs to Grow On? (1950).

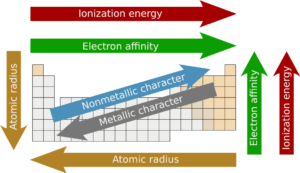

Blackface minstrel John White with his banjo. Source: Bedford of Haverstraw, New York

Blackface minstrel John White with his banjo. Source: Bedford of Haverstraw, New York

Minstrelsy left an indelible mark on the American music and entertainment industries. Faced with practically nonexistent means of upward mobility, Black musicians began forming blackface minstrel troupes themselves in the late 1800s, leading to the proliferation of ragtime, vaudeville, and, eventually, the birth of the American musical. Blackface inspired the original Mickey Mouse, whose physical features and antics were directly borrowed from minstrelsy. The first American sound film, The Jazz Singer (1927), featured a Jewish singer whose dream was to become a blackface minstrel. Judy Garland played a blackface ?pickaninny? in Everybody Sing (1938), and Disney?s Song of the South (1946) ? steeped in blackface stereotypes ? was never released on home video because of its offensive nature.

Judy Garland playing a blackface ?pickaninny? in ?Everybody Sing? (1938).

More disturbingly, the objectification of Black bodies in minstrel shows and other performative acts of violence of that era ? including carnival amusements and public lynching ? conditioned White audiences to believe that African Americans were meant to be physically abused and that their bodies were immune to pain. The normalization of violence against African Americans has repercussions that are still felt today, as Black Americans are less likely than White Americans to receive medical treatment for pain, and young Black males are up to 13 times more likely to die from homicide than non-Hispanic White males.

Carnival amusements of the 19th and 20th centuries aimed at abusing Black Americans. Courtesy of the Jim Crow Museum

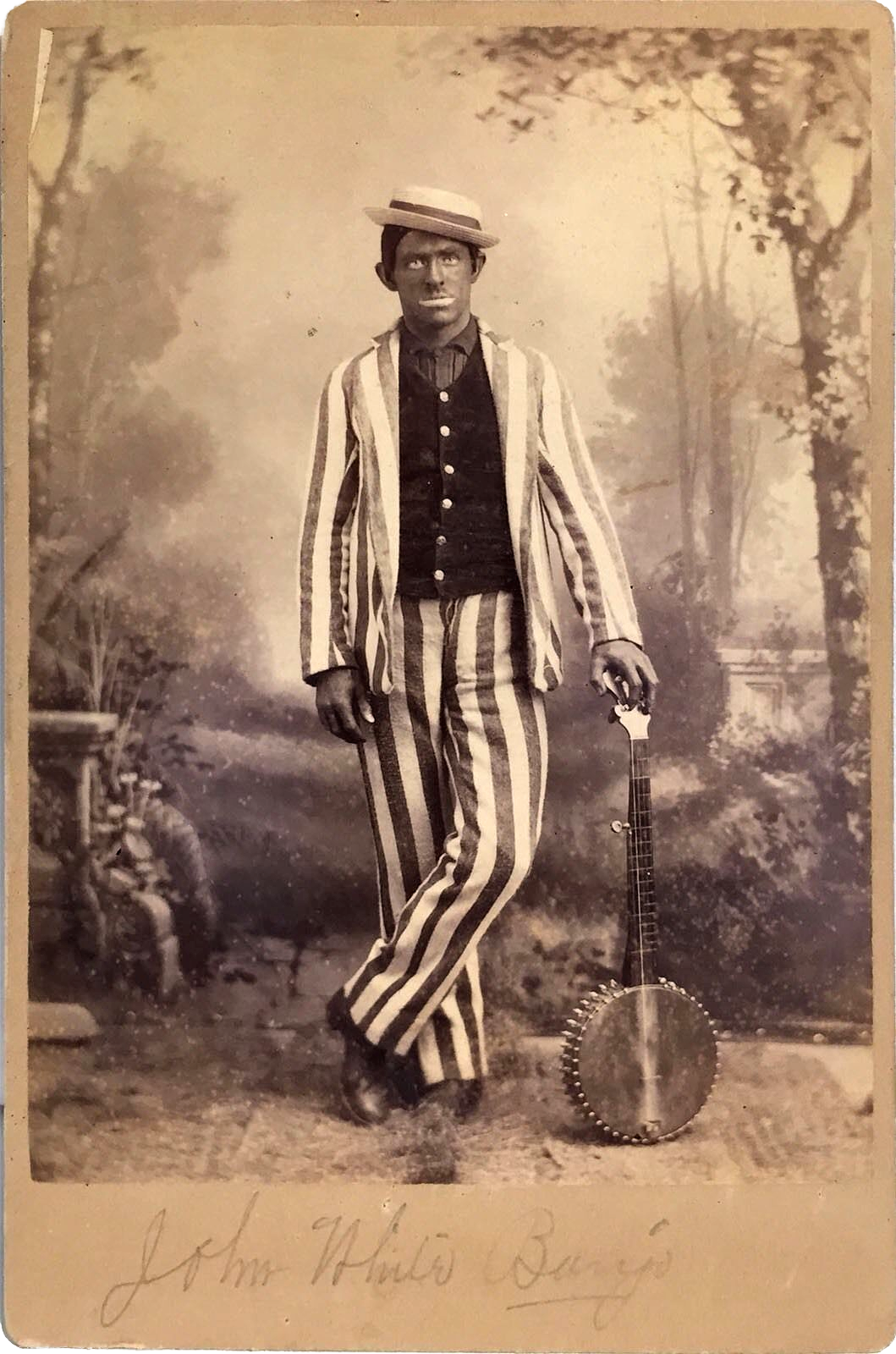

Lyrics to ?Levee Song.? Source: ?Carmina Princetonia? (1894)

Lyrics to ?Levee Song.? Source: ?Carmina Princetonia? (1894)

?I?ve Been Working on the Railroad? is based on the minstrel tune ?Levee Song,? first published by Princeton University students in 1894. Caricaturing the African American laborers who built the levee and railroad systems in the 19th and early 20th centuries, ?Levee Song? was a hit on college campuses and by 1920 became known by the line from its popular chorus, ?I Been Wukkin? on de Railroad.?

The song?s publication in caricatured Black dialect continued into the 1940s, with lyrics that reflected the physically abusive and highly exploitative conditions for laborers in railroad and levee camps. The camp workday began early (?rise up, so uhly in de mawn??), the hours were long (?I been wukkin? on de railroad all de live long day?), and White foremen enforced abusive conditions through disciplinary violence (?doan? yuh hyah de capn? shoutin??), which occasionally resulted in death.

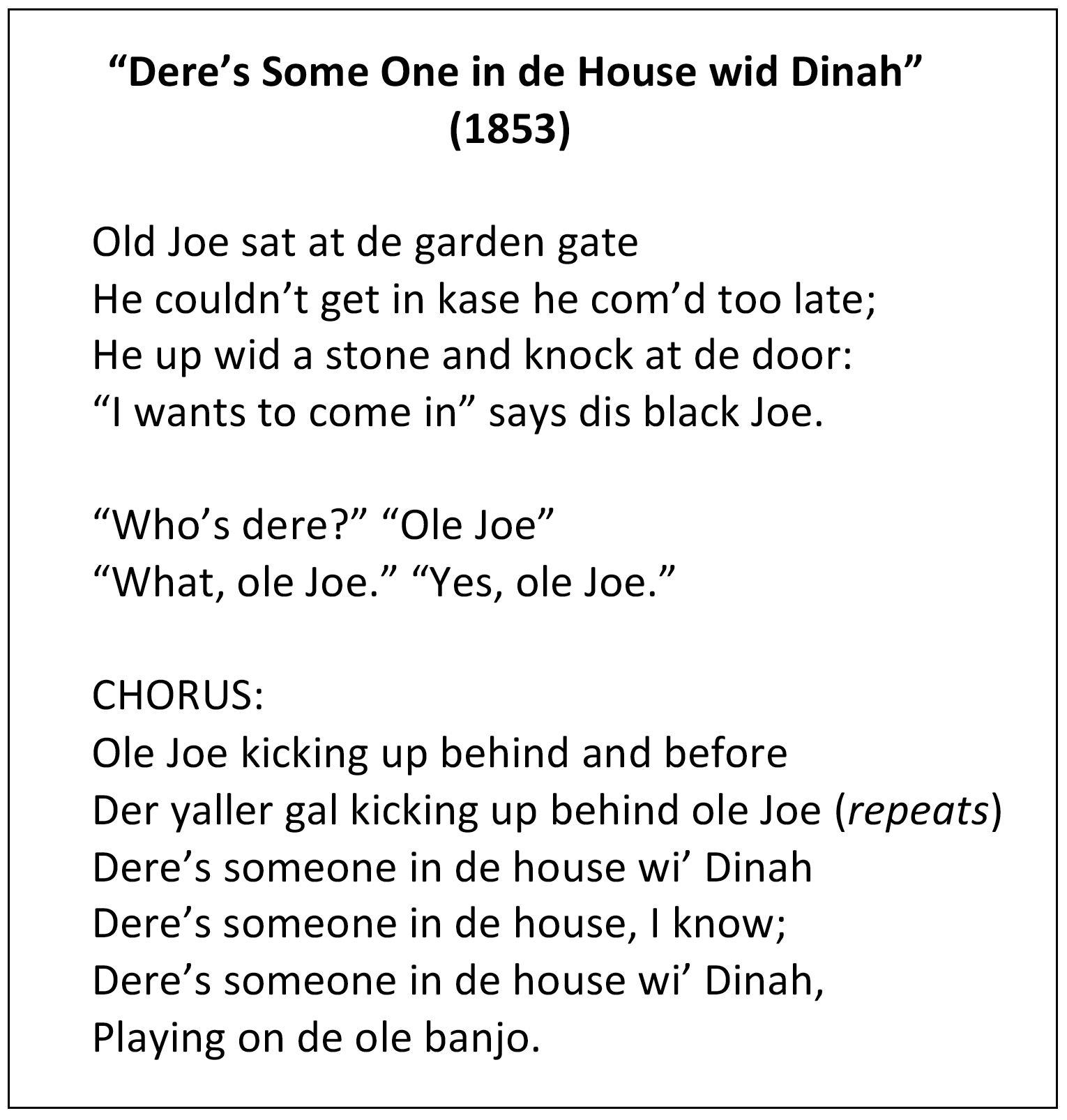

Dinah, the railroad camp cook whose meal is so eagerly awaited by the laborers (?Dinah, blow yo? hawn!?) is a character from another minstrel song, ?Old Joe,? or ?Dere?s Some One in de House wid Dinah.? Dinah was a 19th-century generic name for an African American woman, recalling Aunt Dinah, the untidy slave cook of Harriet Beecher Stowe?s Uncle Tom?s Cabin (1852).

Lyrics to ?Dere?s Some One in De House wid Dinah.? Source: ?Gordon?s Universal Melodist,? London: G.H. Davidson (1953)

Lyrics to ?Dere?s Some One in De House wid Dinah.? Source: ?Gordon?s Universal Melodist,? London: G.H. Davidson (1953)

In ?Dere?s Some One in de House wid Dinah,? a drunken plantation laborer, Old Joe, flies into a rage when he realizes that someone, ?playin? on de ole banjo,? is in the house with his mistress, Dinah. Like many minstrel songs, ?Dinah? employs the classic minstrel trope of the African American playing the banjo.

By 1915, ?Levee Song? started being published in children?s song collections. In M. Teresa Armitage?s children?s song anthology, Junior Laurel Songs, ?Levee Song? was published in caricatured Black dialect but was euphemistically described as an ?old popular song.?

By the mid-20th century, publishing minstrel songs in caricatured Black dialect became unacceptable, and the lyrics to minstrel songs started appearing in standard English spelling. Beatrice Landeck, in her 1950 anthology, Songs to Grow On, published ?I?ve Been Working on the Railroad? in standard English and called it ?one of the classic American community songs? that mysteriously ?sprung from nowhere.? The songbook?s accompanying illustration, however, betrayed the editors? knowledge of the song?s true roots.

The folk revivalist Pete Seeger similarly downplayed the historical roots of ?I?ve Been Working on the Railroad.? The liner notes to Seeger?s first recording of the song in 1963 innocuously describe ?Railroad? as an ?old 19th-century ditty? that ?just keeps changing and rolling along.?

The mythologizing of ?I?ve Been Working on the Railroad? as a tune celebrating American values has continued into recent decades. When Smithsonian Folkways reissued Seeger?s recording in 1990, the liner notes touted the ?democratic passion? of folk revivalists to include the ?music of working-class Americans? as part of the ?national cultural conversation.? The Black Americans represented in ?Railroad,? however, barely had any rights as laborers in railroad camps and arguably still lack basic rights as Americans today.

Some will argue that blackface minstrelsy took place so long ago and that these children?s songs no longer represent that racist history. That history, however, was not that long ago: The last generation born in the segregated South still lives among us today. Black Americans won the right to vote a mere 50-odd years ago. The fallout from slavery and Jim Crow manifests itself today in the form of voter suppression, housing segregation, disproportionate imprisonment, and poverty. Historical trauma ? scientifically proven to be passed down through your DNA ? and the lack of equal access to health care mean that Black Americans are still disproportionately suffering from physical and mental illness and decreased lifespan.

Some will argue that blackface minstrelsy took place so long ago and that these children?s songs no longer represent that racist history. That history, however, was not that long ago: The last generation born in the segregated South still lives among us today. Black Americans won the right to vote a mere 50-odd years ago. The fallout from slavery and Jim Crow manifests itself today in the form of voter suppression, housing segregation, disproportionate imprisonment, and poverty. Historical trauma ? scientifically proven to be passed down through your DNA ? and the lack of equal access to health care mean that Black Americans are still disproportionately suffering from physical and mental illness and decreased lifespan.

Yet others will argue that music exists on its own, immune to history or context. Music and history, however, are inextricably tied. You need no more proof of the power of music in shaping thought and history than in the very name for America?s system of segregation ? ?Jim Crow? ? as having come from the first blackface minstrel character.

Still others will be left in a panic that there will be no traditional songs left to sing, as Martin Urbach has observed. That is simply not true. There are many traditional songs without racist pasts, including a rich abundance of music by actual African Americans, like the children?s singing game ?Little Johnny Brown? or jazz standards like ?When the Saints Go Marching In.? Play-party songs by early European American settlers, like ?Old Brass Wagon,? are also appropriate substitutes for minstrel songs.

Minstrel songs belong where their historical role can be explored in depth ? in museums and history classrooms of higher education. Or they belong reclaimed by African American artists like Rhiannon Giddens, who is reinterpreting minstrel songs while exposing their troubling roots.

Some organizations are leading the way in supporting research on minstrel songs and advocating for broad curriculum reforms. The early childhood music program Music Together Worldwide recently removed all minstrel songs from their curriculum based on research conducted by musicologists on their newly formed Song Advisory Board. The pioneering group of music educators at Decolonizing the Music Room, organized by Brandi Waller-Pace, are providing guidance and resources for educators eager to remove these and other culturally offensive songs from music curricula.

Removing minstrel songs from children?s music programs will not undo the damage already done by blackface minstrelsy. Their removal, however, would serve as an acknowledgment of the damage wrought by these songs and a pledge to no longer promote that legacy. Our children won?t know the difference now, but one day they will be grateful for our efforts to rid their classrooms ? and their childhoods ? of racist songs that were once powerful instruments of oppression.