Listen to this story

–:–

–:–

So many of our relationships are accidental. Here?s how to develop friendships that matter.

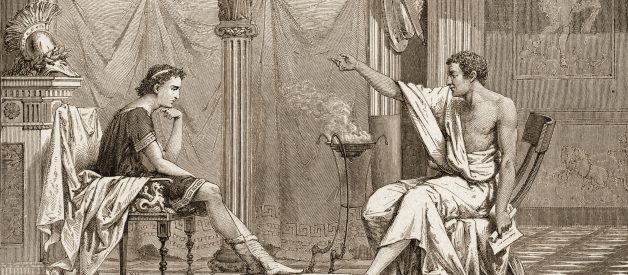

Image: Stock Montage/Getty

Image: Stock Montage/Getty

Aristotle is widely regarded one of the most brilliant and prolific among the Western philosophers. It?s impossible to say how much he wrote, but the fraction of his work still around today is stunning in scope. Every field, from astronomy and physics to ethics and economics, has been influenced by his thinking. For more than 2,000 years, he?s remained one of the most widely read and quoted thinkers in history.

Aristotle is widely regarded one of the most brilliant and prolific among the Western philosophers. It?s impossible to say how much he wrote, but the fraction of his work still around today is stunning in scope. Every field, from astronomy and physics to ethics and economics, has been influenced by his thinking. For more than 2,000 years, he?s remained one of the most widely read and quoted thinkers in history.

While Aristotle?s impact can still be felt in many disciplines, one of his most enduring observations relates to friendship. He saw friendship as one of the true joys of life, and felt that a life well-lived must include truly meaningful, lasting friendships. In his words:

In poverty as well as in other misfortunes, people suppose that friends are their only refuge. And friendship is a help to the young, in saving them from error, just as it is also to the old, with a view to the care they require and their diminished capacity for action stemming from their weakness; it is a help also to those in their prime in performing noble actions, for ?two going together? are better able to think and to act.

The accidental friendships

Aristotle outlined two common kinds of friendships that are more accidental than intentional. We often fall into these kinds of friendships without realizing it.

The first is a friendship of utility. In this relationship, two parties are not in it for affection. Rather, they?re in it for the benefit each receives from the other. These relationships are temporary: whenever the benefit ends, so does the relationship. Aristotle observed that these relationships of utility were most common among older people.

Think of a business or work relationship, for example. You may enjoy the time you spend together, but once the situation changes, so does the nature of your connection.

Aristotle?s second kind of accidental friendship is based in pleasure. This kind of relationship, he found, was more common among younger people. Think of your college friends or people who play in the same sports league. Their relationship is grounded in the emotion they feel at a given time or during a certain activity.

These friendships are often the most short-lived relationships of our lives. And that?s fine, as long as the two parties gain enjoyment through a mutual interest in something external. But these friendships inevitably end when either person?s tastes or preferences change. Many young people go through phases in what they enjoy. Quite often, their friends change along the way.

Most friendships fall into these two accidental categories, and while Aristotle didn?t necessarily see them as bad, he did feel their lack in depth limited their quality. It?s fine, and even necessary, to have accidental friendships ? but there?s far more out there.

The friendship of the good

Aristotle?s final form of friendship seems to be the most preferable. Rather than utility or pleasure, this kind of relationship is based on a mutual appreciation of the virtues the other person holds dear. In this kind of friendship, the people themselves and the qualities they represent provide the incentive for the two parties to be in each other?s lives.

Friendships of virtue take time and trust to build. They depend on mutual growth.

Rather than being short-lived, such a relationship endures over time, and there?s generally a base level of goodness required in each person for it to exist in the first place.

People who lack empathy and the ability to care for others seldom develop these kinds of relationships because their preference tends toward pleasure or utility. What?s more, friendships of virtue take time and trust to build. They depend on mutual growth.

We?re much more likely to connect at this level with someone when we?ve seen them at their worst and watched them grow ? or if we?ve endured mutual hardship with them.

Beyond their depth and intimacy, the beauty of these relationships is in how they include the rewards of the other two types. They?re beneficial and pleasurable. When you respect a person and care for them, you gain joy from spending time with them. If they?re a good enough person to warrant such a relationship to begin with, there?s utility there, too. They help maintain your mental and emotional health.

These relationships require time and intention, but when they blossom, they do so with trust, admiration, and awe. They bring with them some of the sweeter joys that life has to offer.

Aristotle?s legacy

There?s a good reason Aristotle?s work continues to be read some 2,000 years after his death. Not everything he wrote is relevant today, of course, and many of his assumptions have been argued against. He taught us to examine the world empirically, and he inspired generations of thinkers and philosophers to consider the role and value of ethics in the everyday conduct of our lives, including our relationships.

Life is too short for shallow friendships.

While he saw the value in accidental friendships based on pleasure and utility, he felt that their impermanence diminished their potential. They lacked depth and a solid foundation.

Instead, he argued for the cultivation of virtuous friendships built with intention and based on a mutual appreciation of character and goodness. He knew these friendships could only be strengthened over time ? and if they did thrive, they?d last for life.

We are, and we live through, the people we spend time with. The bonds we forge with those close to us directly shape the quality of our lives. Life is too short for shallow friendships.

Want more?

I write about philosophy, science, art, and history for a private community of smart, curious people. Join 40,000+ readers for exclusive access.