Illustrations: Ariel Davis

Illustrations: Ariel Davis

Its App Store has a choke hold on your devices. That may not last much longer.

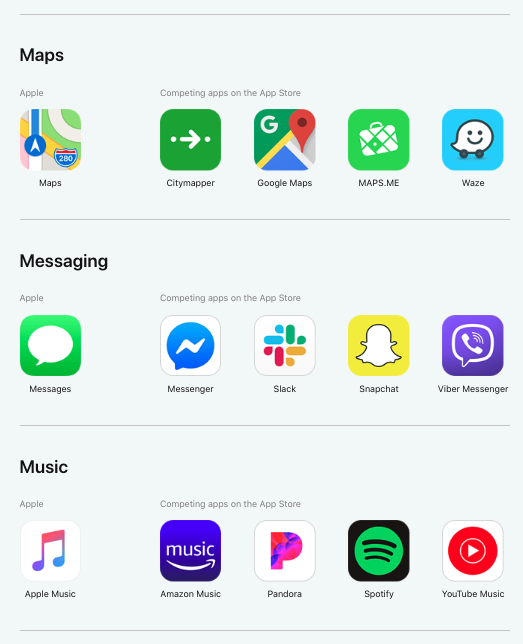

Smaller app developers, meanwhile, have little choice but to play by Apple?s rules. That?s true even when they?re competing with Apple?s own apps, which pay no such fees and often enjoy deeper access to users? devices and information.

Now, a handful of developers are speaking out about it ? and government regulators are beginning to listen. David Heinemeier Hansson, the co-founder of the project management software company Basecamp, told members of the U.S. House antitrust subcommittee in January that navigating the App Store?s fees, rules, and review processes can feel like a ?Kafka-esque nightmare.?

One of the world?s most beloved companies, Apple has long enjoyed a reputation for user-friendly products, and it has cultivated an image as a high-minded protector of users? privacy. The App Store, launched in 2008, stands as one of its most underrated inventions; it has powered the success of the iPhone?perhaps the most profitable product in human history. The concept was that Apple and developers could share in one another?s success with the iPhone user as the ultimate beneficiary.

?If you want to publish modern software, it?s essentially suicide not to have a presence on the iPhone.?

? David Heinemeier Hansson, co-founder of Basecamp

It worked beyond the wildest expectation. According to the analyst App Annie, Apple customers downloaded 32 billion iOS apps in 2019, spending a total of $58 billion, and that?s before you get to the billions in ad revenue those apps brought in. The App Store has become a major global industry unto itself.

But critics say that gauzy success tale belies the reality of a company that now wields its enormous market power to bully, extort, and sometimes even destroy rivals and business partners alike. The iOS App Store, in their telling, is a case study in anti-competitive corporate behavior. And they?re fighting to change that ? by breaking its choke hold on the Apple ecosystem.

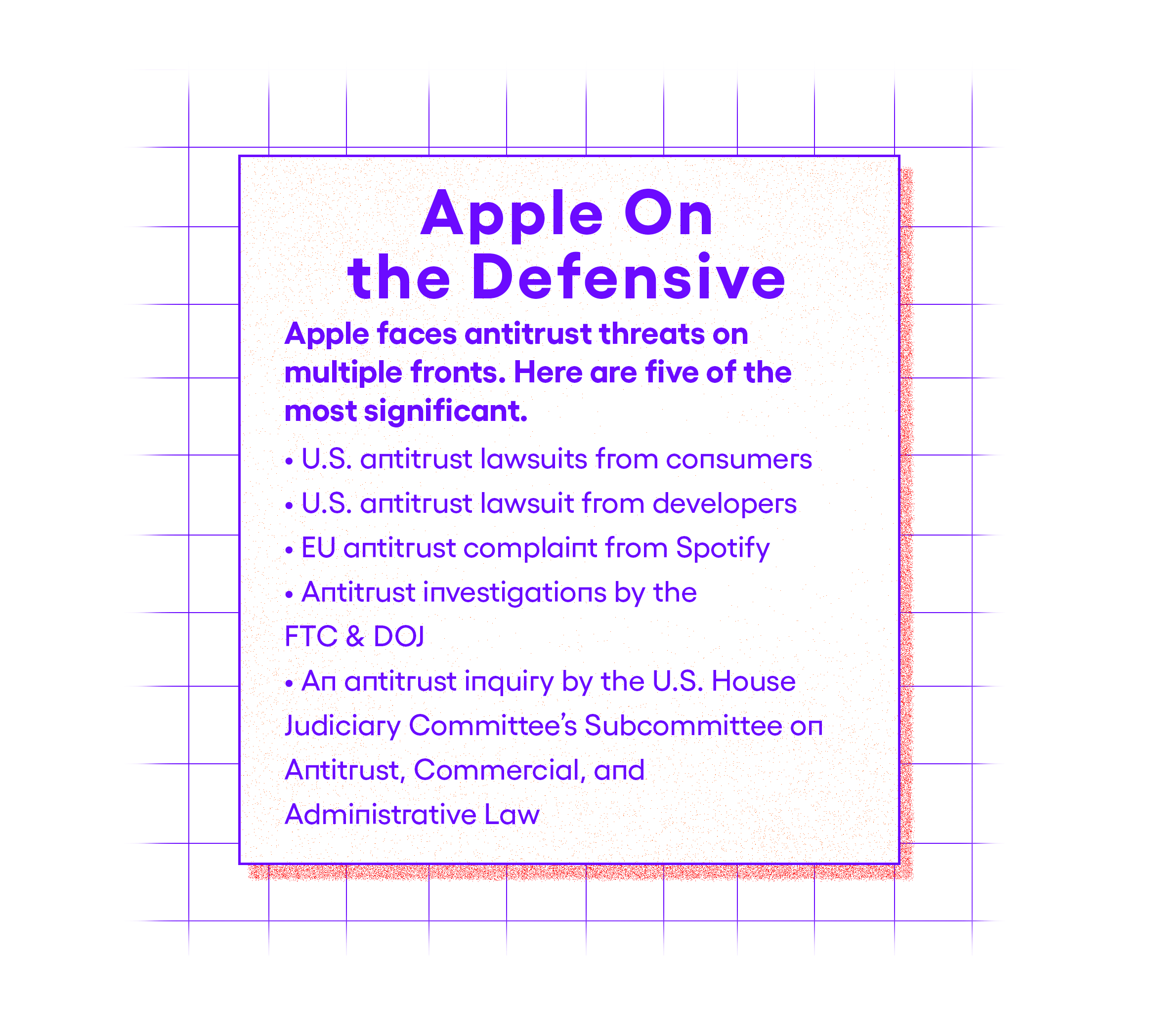

The company faces an antitrust lawsuit from consumers; a separate antitrust lawsuit from developers; a formal antitrust complaint from Spotify in the European Union; investigations by the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice; and an inquiry by the antitrust subcommittee of the U.S House of Representatives. At stake are not only Apple?s profits, but the future of mobile software.

Apple insists that it isn?t a monopoly, and that it strives to make the app store a fair and level playing field even as its own apps compete on that field. But in the face of unprecedented scrutiny, there are signs that the famously stubborn company may be feeling the pressure to prove it. For example, just last week, Bloomberg reported that Apple is considering allowing users to change the default mail and web browser apps on their iPhones and iPads, replacing Apple?s own Mail and Safari with rival apps such as Gmail and Firefox.

Apple rightly points out that allowing third-party apps to track users? location can raise serious privacy concerns, and says it?s always working on ways to balance users? privacy with developers? ability to make their apps as useful as possible.

In a letter to the antitrust subcommittee obtained by OneZero, Apple?s vice president and chief compliance officer, Kyle Andeer, noted that Apple doesn?t restrict the ability of third-party apps such as Tile to track users? location ? it just makes sure the user is aware of it. ?Stronger privacy protections may not be in everyone?s business interest, but they are in the interest of every person with a smartphone,? Andeer wrote. Apple also told OneZero it?s working with developers interested in an ?always allow? option for location-tracking to provide users that choice when they first set up the app.

Tile is hardly alone in its grievances. Apple?s penchant for copying key features of third-party apps and integrating them into its operating system is so well-known among developers that it has a name: ?Sherlocking.? It?s a reference to the time?in the early 2000s?when Apple kneecapped a popular third-party web-search interface for Mac OS X, called Watson. Apple built virtually all of Watson?s functionality into its own feature, called Sherlock.

In a 2006 blog post, Watson?s developer, Karelia Software, recalled how Apple?s then-CEO Steve Jobs responded when they complained about the company?s 2002 power play. ?Here?s how I see it,? Jobs said, according to Karelia founder Dan Wood?s loose paraphrase. ?You know those handcars, the little machines that people stand on and pump to move along on the train tracks? That?s Karelia. Apple is the steam train that owns the tracks.?

From an antitrust standpoint, the metaphor is almost too perfect. It was the monopoly power of railroads in the late 19th century ? and their ability to make or break the businesses that used their tracks ? that spurred the first U.S. antitrust regulations.

There?s another Jobs quote that?s relevant here. Referencing Picasso?s famous saying, ?Good artists copy, great artists steal,? Jobs said of Apple in 2006. ?We have always been shameless about stealing great ideas.? Company executives later tried to finesse the quote?s semantics, but there?s no denying that much of iOS today is built on ideas that were not originally Apple?s.

To be fair, this is true of a great many successful companies; business success has always depended on marketing and execution, not just innovation. Still, the App Store?s history is littered with companies that rose to prominence only for Apple to incorporate and profit from their inventions.

Tile believes it represents one such invention. So does Blix, the developer of an email app called BlueMail, which included an anonymous sign-in feature. Blix says Apple copied its idea for its new Sign In With Apple feature, which it is now requiring of every app developer that allows social logins. Days after the feature was announced in June 2019, Blix says, Apple kicked BlueMail off of its Mac App Store.

Apple maintains that was for security reasons, and that its offers to help Blix get back on the store were rebuffed. ?The App Store has a uniform set of guidelines, equally applicable to all developers, that are meant to protect users,? the company said in a statement to OneZero and other media outlets. ?Blix is proposing to override basic data security protections which can expose users? computers to malware that can harm their Macs and threaten their privacy.?

Blix responded to its removal by suing Apple for patent infringement, writing an open letter to CEO Tim Cook in November 2019, and recruiting other developers who felt wronged by Apple to join its cause. In February 2020, Apple restored BlueMail to the Mac App Store, but Blix says it is not dropping its lawsuit. Blix co-founder Dan Volach said in a statement that Apple?s response proved the value of speaking out. ?When we wrote to Apple?s developer community, BlueMail was back on the App Store within a week.?

An Apple chart depicting rival apps that it feels offer services similar to its own. Credit: Apple

An Apple chart depicting rival apps that it feels offer services similar to its own. Credit: Apple

Apple ? and its cardinal simplicity ? are beloved for a reason. There is something to be said for Apple?s ability to integrate new features into its operating system, even if that puts some apps out of business. It?s hard to see how consumers were better off, for instance, when turning their iPhone into a flashlight required opening the App Store, navigating a slew of competing flashlight apps from developers they?ve never heard of, and trying to figure out which ones were legit and which were trying to spam them with ads or mine their data.

And while it can feel unfair for Apple to give its own apps access that third-party rivals lack, figuring out which third-party apps deserve what levels of access is undoubtedly tricky. It might sound simple to leave all such decisions to the user, but that presupposes a level of sophistication that it?s unreasonable to expect of the average iPhone owner. It also presupposes good faith on the part of every developer, when in reality there are plenty of scammers out there.

It?s tough to make the case for curbing a company whose public image is sparkling.

The problem is when Apple uses those excuses to justify actions that privilege its own business over those of legitimate rivals ? a trend that Cicilline remarked on at the January hearing. ?I?m increasingly concerned about the use of privacy as a shield for anti-competitive conduct,? he said.

Sherlocking is only one of the ways that Apple wields its power over other firms. And in some cases, it?s hard to see the benefit to anyone other than Apple itself.

Sweden-based Spotify, whose streaming app competes directly with Apple?s own Apple Music, last year filed a formal complaint against Apple with the European Union?s antitrust regulators. It also launched a site called Time to Play Fair, calling attention to Apple?s alleged abuses. The company claimed that Apple repeatedly rejected or delayed approval of updates to the Spotify app, degrading the quality of its product, while working on Apple Music.

?They continue to give themselves an unfair advantage at every turn,? CEO Daniel Ek wrote. In the App Store, he said, Apple was acting as both ?player and referee,? a metaphor that echoed Warren?s framing in her call to break up big tech platforms. (Though she didn?t mention Apple at first, Warren has since clarified that she thinks Apple should be broken up too.)

Apple has responded with its own marketing website touting the App Store as a boon to consumers and developers alike: ?Since the launch of the App Store, an entire industry has been built around app design and development, generating over 1,500,000 U.S. jobs and over 1,570,000 jobs across Europe.?

Still, the signs of discontent are growing. On February 13, Google?s YouTube TV became the first major streaming app to announce it would not only prohibit new signups through iOS, but disable the accounts of existing users unless they switch to paying Google directly. In that case, there?s no moral high ground: Google takes the same 30% cut from mobile apps that use its Google Play Store on Android.

That same week, at a game conference in Las Vegas, Tim Sweeney, CEO of Fortnite-maker Epic Games, railed against both Apple and Google for their high fees, and for discouraging users from using other app stores, such as Epic?s own Epic Games Store, which takes only a 12% cut from developers. He contrasted Apple and Google?s rates with the 2% to 3% fees charged by credit card companies. In the world of gaming and apps, Sweeney said, ?Undue power has accrued to participants in the supply chain who are not at the core of the industry.?

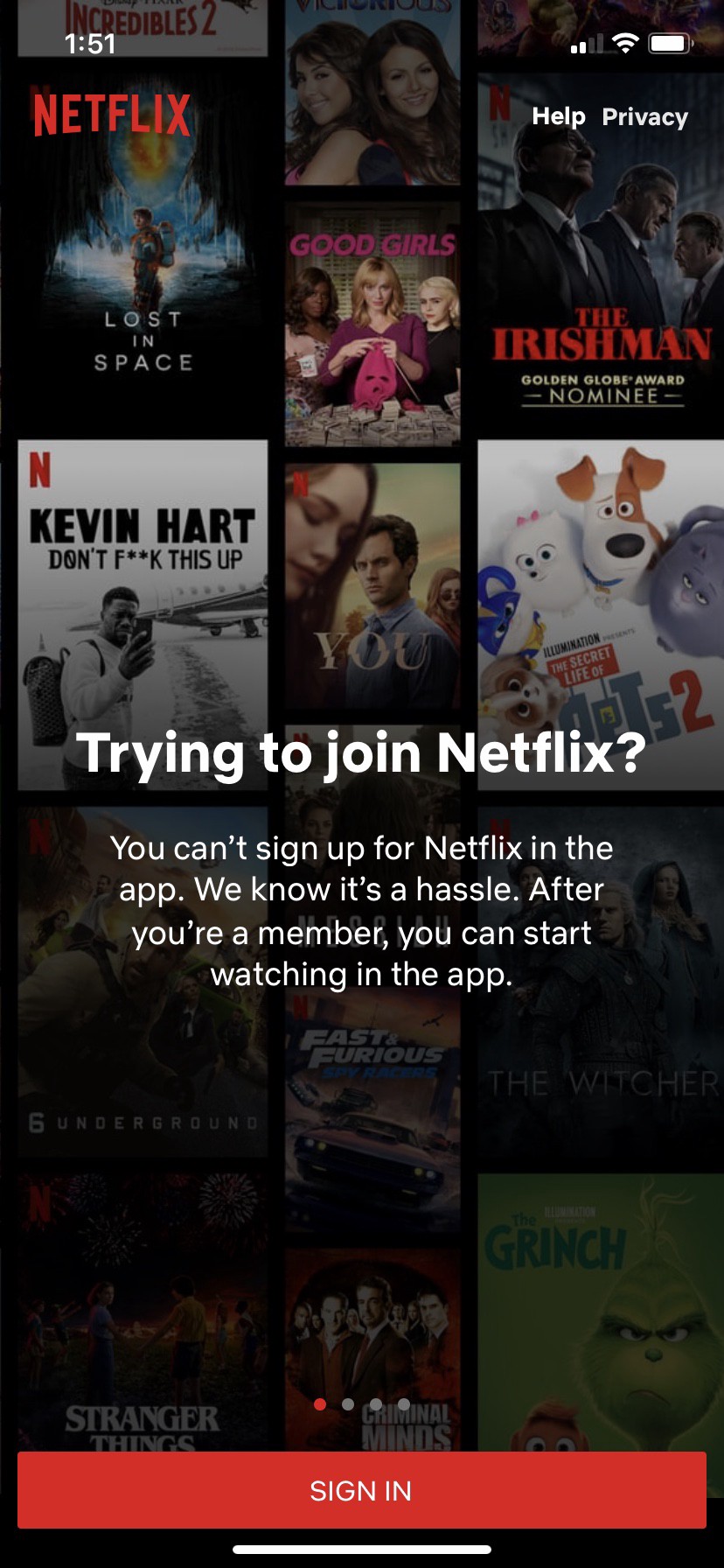

Most developers, of course, have nowhere near the scale or resources of those Goliaths. At the same House antitrust subcommittee hearing in which Tile testified, Basecamp?s Hansson decried the effects of Apple?s terms and payment policies on developers of more modest means. Basecamp is among the companies that has tried to encourage users to sign up outside of its iOS app. Its attempts to do so have landed it in app-review purgatory more than once. ?It?s a horrible experience for users,? Hansson said.

Tech companies sometimes dismiss criticism on the grounds that their critics don?t understand the industry. But at the Colorado hearing, all four of the major witnesses ? from Tile, Basecamp, Sonos, and PopSockets ? represented tech-savvy startups. Hansson, in particular, is a legend among computer programmers, having invented the popular coding language Ruby on Rails.

Lawmakers from both sides of the aisle sounded moved, persuaded, and, in some cases, shocked by the testimony. While the Democrats called the hearing, Colorado Republican Rep. Ken Buck appeared equally chagrined by Apple?s behavior and interested in possible remedies. ?I think it?s clear there?s abuse in the marketplace and a need for action,? Buck said.

Hansson said he was gratified by the response. ?There wasn?t a clear consensus about what needs to be done. But just the fact that we can agree on the problem, in this day and age, is amazing.?

Meanwhile, legal thinkers such as Khan and Columbia Law School?s Tim Wu, author of The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Gilded Age and an occasional OneZero contributor, are calling for a return to the robust federal antitrust enforcement of yore, with big tech firms as their top target. Wu has long maintained that Apple?s ?walled garden? represents a threat to competition and the open internet. And while Khan is most famous for her critique of Amazon, she argued in a recent Columbia Law Review paper that Apple is among the platforms whose incentives and behavior suggest a need for greater regulation. She contends that the consumer welfare framework in antitrust is ill-suited to online platforms, which often pursue growth over profit and use their dominance in one sector to crush competitors in other sectors through favoritism or predatory pricing. Khan declined to comment for this story given her ongoing work on the antitrust subcommittee.

If Apple is indeed acting like a monopoly, the question becomes what to do about it. Warren?s proposal was to prohibit the very largest companies from both operating a platform for online commerce and participating in it by selling their own products there. For Apple, that would presumably mean either spinning off the App Store as a separate company, or ceasing development of its own apps. That would shake up the company dramatically.

But Warren is trailing in the Democratic primaries; Trump?s DOJ antitrust chief Makan Delrahim is running a relatively business-friendly department; and Congress probably lacks the unity to pass such decisive measures anytime soon. Few antitrust experts see a breakup as imminent.

A more modest measure, and perhaps a more realistic one in the short run, would be to require Apple to allow sideloading of apps on iOS, as Google does on Android. Among the apps you could sideload would be alternative app stores, which could charge developers lower rates, or offer apps banned on the official iOS App Store.

Apple would likely raise a fuss about the dangers of third-party app stores, and the security concerns of allowing non-Apple-approved software on iOS devices are ?not trivial,? the EFF?s Stoltz acknowledged. ?But there is an element of paternalism? to that stance, he added. ?In the ideal world, the consumer has their choice of app stores and app developers.?

Public Knowledge?s Bergmayer believes allowing sideloading would make a lot of sense as a first step. It could help to defuse some of the concerns around fairness and competition, he said, without preventing Apple from continuing to control its own App Store or develop its own new apps and features.

?I don?t think you have to be totally extreme and say they can?t innovate, they can?t change, they can never do anything? that could hurt rivals, Bergmayer said. ?Or that everything has to be entirely open with no restrictions? on what apps users can install. Instead, he suggested, platform owners as large and resourceful as Apple should be expected to develop security measures that allow for a degree of openness while protecting everyday users from bad actors. Ideally, those expectations wouldn?t be limited to Apple alone: Public Knowledge has called on Congress to pass a Digital Platform Act, creating a new regulatory authority focused on digital markets.

By now, many app-makers recognize that the possibility of having your app Sherlocked is just part of the cost of doing business on iOS. Ditto Apple?s hefty cut and ever-changing terms. So far, it doesn?t seem to be slowing down the app economy. App Annie?s annual State of Mobile report, released this month, found that consumer spending on iOS apps jumped from $50 billion in 2018 to $58 billion in 2019. And the analytics firm SensorTower projects it will approach $100 billion by 2023.

By now, many app-makers recognize that the possibility of having your app Sherlocked is just part of the cost of doing business on iOS. Ditto Apple?s hefty cut and ever-changing terms. So far, it doesn?t seem to be slowing down the app economy. App Annie?s annual State of Mobile report, released this month, found that consumer spending on iOS apps jumped from $50 billion in 2018 to $58 billion in 2019. And the analytics firm SensorTower projects it will approach $100 billion by 2023.

Developers may not like the 30% cut taken by Apple and Google, said Amir Ghodrati, App Annie?s director of market insights, in a phone conversation. But given the iOS market?s size and continued growth, most developers find it worth the trade-off compared to trying to get their users to pay directly. As for competition with Apple?s own apps, he noted that some categories fare better than others. Apps that provide a utility or tool ? such as Tile ? may see their downloads drop off dramatically when Apple incorporates similar features. But those that offer exclusive content, such as games and streaming apps, can often hold their own against Apple?s offerings.

Some developers have managed to weather the vicissitudes of the App Store by staying agile and persisting in the face of setbacks. A 2016 Verge feature profiled a struggling maker of graphics editing apps called Pixite to show how tenuous the business model could be. At the time, the company?s future was in doubt. But when I emailed Pixite this month to see how they were holding up, co-founder Eugene Kaneko responded enthusiastically. ?A lot has happened since that article,? he said in an email. ?We?ve adopted the subscription business model, doubled in size, and now thriving. We?re also about to release our 17th app on the App Store in a couple of weeks and have a feeling it?s going to be big.?

The ongoing app boom isn?t surprising when you consider that users spent an average of three hours and 40 minutes per day on their mobile devices. In other words, humans around the world now spend more than a fifth of their waking lives on their phones. It?s where we stream media, socialize, read the news, speak in the public square, game, create art, connect our smart homes, do business, and more. And for those on iPhones, Apple holds unilateral control over every aspect of that experience ? for now.

In June, when it was first reported that the DOJ and FTC were launching antitrust investigations of Apple and other top tech firms, Apple?s Cook insisted his company is ?not a monopoly.? He also criticized the idea of separating platforms from commerce, noting the long history of brick-and-mortar sellers such as Walmart stocking house brands alongside third-party goods.

By December, Cook seemed to be hedging his bets. While maintaining that Apple isn?t a monopoly, he mused in an interview that ?a monopoly by itself isn?t bad if it?s not abused.? He went on, ?The question for those companies is, do they abuse it? And that is for regulators to decide, not for me to decide.?

Update: A previous version of this article misstated the nature of Spotify?s action against Apple in the European Union. It is a formal antitrust complaint. A previous version also misstated the timing of Apple?s rollout of period-tracking features, and their inclusion in its HealthKit API. They occurred simultaneously.

In addition, the story has been updated to reflect Apple?s latest data on the amount of money it has paid to developers, and to include a link to its full response to the House antitrust subcommittee, which was made public after this story?s publication.