Anemoia is a new and nearly unheard-of word. Its meaning is just as the title would suggest; a nostalgic sense of longing for a past you yourself have never lived. It is nostalgia for the ?good ol? days?; more specifically, the good ol? days you are too young to have known. It is a sense that something was intrinsically better in the distant past than it is in the present; that we?ve lost something crucial in our ceaseless march of progress. Few haven?t felt it. Fewer still have contemplated if it really has a meaning behind senseless longing.

Nostalgia has long been known to not represent the actual past, but rather, the past as we imagine it. It is a fantasy; plain and simple. Its yearnings are not for times we really experienced, but for times we?d like to think we experienced. This makes sense when taken into a personal context; we tend to see our own early years as more idyllic than they really were. It puts at ease the worries and conflicts of those days and replaces them with reassurances that everything was alright. It dismisses our past failures and shortcomings so they cannot distract us from the present. When taken into a historical context, however, this explanation falls embarrassingly short. Nostalgia for your own past makes sense. Nostalgia for a past not your own ? anemoia ? is utterly bewildering. Why, then, does it occur?

History is infamous for its inaccuracies. The historical record is but the tip of an endless iceberg we may never fully uncover, and this makes it ripe for the prying eyes of nostalgia. In olden days, when oral traditions and individual scholars dictated our histories, it was easy for elders to pass down embellished stories to their descendants. Even now, some people plainly reject reality to continue living in more comfortable fantasies. Thus, it may be stated that anemoia is the product of a buildup of normal nostalgia. People remember the past inaccurately and pass those inaccuracies down. Later people hear those stories and embellish them even further. Thus, the further one goes back into the past, the more embellished and idyllic that past becomes. Nostalgia has a tendency to paint our own pasts as better than they really were. Anemoia does the same, but on a far larger scale.

Still, despite this seemingly reasonable explanation, there are those who maintain that the past had something that the present lacks. We could simply dismiss their claims as unsubstantiated, but it would do us all a disservice. Thus, we must look to the past in search of what it had that the present hasn?t. And, although anemoia and its biases make this no simple search, we can still find one glaringly obvious answer. The past had a sense of belonging that the present cannot hope to match. The further we delve into history, the more glaringly we see that its inhabitants enjoyed a powerful assuredness in their communal bonds. Those in the earliest days of history lived the way evolution sculpted us to live; that is, intertwined with local communities, cultures, and beliefs. There was, at least between people of the same descent, a true and tangible brotherhood of man.

It is definitely disingenuous to say that people lived in peace. It is very much possible, however, that people lived with peace of mind. Nowadays, while we are more connected than ever, it is well-accepted that we feel evermore alone. In comparison, our ancestors ? especially our ancient ancestors ? while ostensibly worse off, shared an unbreakable bond between each other that we today can barely even conceive of. This may very well be the part of the past that the people of today long for. Thus, anemoia may not be an empty feeling after all. This is, of course, only speculation, but it is important speculation nonetheless, for it presents to us both a problem and its solution. The problem, of course, is that the modern age lacks the social cohesion of the ages that came before it. The solution is to reconstruct this social cohesion without sacrificing any of our social progress in the process. This, obviously, is no small feat, and concrete policies regarding it are far away. Still, we may at least begin our considerations here.

The primary human desire, it can be asserted, is desirelessness. We want to not want anything. We seek, not for the things we think we seek, but to stop seeking things entirely. This ideal state of mind, where all is alright and we need to do nothing but live, has never been easily achieved. In the present, though, it is made exceptionally difficult by our isolation, uncertainty, and mistrust of others. In the past, these problems were minimized by living in tight-knit communities. Thus, to bring it back to prominence in the present, we need to disregard the idea of monstrous nation-states battling for dominance across the globe. We need to let decentralization and local initiatives bring back the kind of communities we were born to live in. Only this time, we need to root them in fact, instead of myth, and maintain among them a spirit of peaceful competition, rather than bloodthirsty animosity.

While these answers may seem simple on paper, they are monumental challenges in practice. Thus, we as individuals may be better off doing what we can to better suit our attitudes to the kind of lifestyle described above. Those steps, fortunately enough, are simple. Take your anemoia and wield it productively. Take whatever draws your awe to other eras and do your best to implement those things in your everyday life. Learn about the ancient heroes your Norse ancestors sang of. Read the poems and sagas your Slavic ancestors wrote down. Wear the symbols of your Celtic ancestors as reminders of your heritage. And, most importantly, join some of the countless communities of people who are already working to keep their traditions and identities alive. From there, we may help ease the pressures of modernity, and eventually, we may help bring about a change far larger than ourselves.

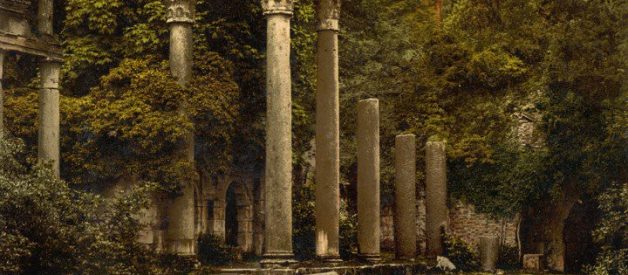

Virginia Water Ruins, England, as depicted on a postcard

Virginia Water Ruins, England, as depicted on a postcard