Closures in JavaScript are one of those concepts that many struggle to get their heads around. In the following article, I will explain in clear terms what a closure is, and I?ll drive the point home using simple code examples.

What is a closure?

A closure is a feature in JavaScript where an inner function has access to the outer (enclosing) function?s variables ? a scope chain.

The closure has three scope chains:

- it has access to its own scope ? variables defined between its curly brackets

- it has access to the outer function?s variables

- it has access to the global variables

To the uninitiated, this definition might seem like just a whole lot of jargon!

But what really is a closure?

A Simple closure

Let?s look at a simple closure example in JavaScript:

function outer() { var b = 10; function inner() { var a = 20; console.log(a+b); } return inner;}

Here we have two functions:

- an outer function outer which has a variable b, and returns the inner function

- an inner function inner which has its variable called a, and accesses an outer variable b, within its function body

The scope of variable b is limited to the outer function, and the scope of variable a is limited to the inner function.

Let us now invoke the outer() function, and store the result of the outer() function in a variable X. Let us then invoke the outer() function a second time and store it in variable Y.

function outer() { var b = 10; function inner() { var a = 20; console.log(a+b); } return inner;}var X = outer(); //outer() invoked the first timevar Y = outer(); //outer() invoked the second time

Let?s see step-by-step what happens when the outer() function is first invoked:

- Variable b is created, its scope is limited to the outer() function, and its value is set to 10.

- The next line is a function declaration, so nothing to execute.

- On the last line, return inner looks for a variable called inner, finds that this variable inner is actually a function, and so returns the entire body of the function inner.[Note that the return statement does not execute the inner function ? a function is executed only when followed by () ? , but rather the return statement returns the entire body of the function.]

- The contents returned by the return statement are stored in X.Thus, X will store the following: function inner() { var a=20; console.log(a+b); }

- Function outer() finishes execution, and all variables within the scope of outer() now no longer exist.

This last part is important to understand. Once a function completes its execution, any variables that were defined inside the function scope cease to exist.

The lifespan of a variable defined inside of a function is the lifespan of the function execution.

What this means is that in console.log(a+b), the variable b exists only during the execution of the the outer() function. Once the outer function has finished execution, the variable b no longer exists.

When the function is executed the second time, the variables of the function are created again, and live only up until the function completes execution.

Thus, when outer() is invoked the second time:

- A new variable b is created, its scope is limited to the outer() function, and its value is set to 10.

- The next line is a function declaration, so nothing to execute.

- return inner returns the entire body of the function inner.

- The contents returned by the return statement are stored in Y.

- Function outer() finishes execution, and all variables within the scope of outer() now no longer exist.

The important point here is that when the outer() function is invoked the second time, the variable b is created anew. Also, when the outer() function finishes execution the second time, this new variable b again ceases to exist.

This is the most important point to realize. The variables inside the functions only come into existence when the function is running, and cease to exist once the functions completes execution.

Now, let us return to our code example and look at X and Y. Since the outer() function on execution returns a function, the variables X and Y are functions.

This can be easily verified by adding the following to the JavaScript code:

console.log(typeof(X)); //X is of type functionconsole.log(typeof(Y)); //Y is of type function

Since the variables X and Y are functions, we can execute them. In JavaScript, a function can be executed by adding () after the function name, such as X() and Y().

function outer() {var b = 10; function inner() { var a = 20; console.log(a+b); } return inner;}var X = outer(); var Y = outer(); //end of outer() function executionsX(); // X() invoked the first timeX(); // X() invoked the second timeX(); // X() invoked the third timeY(); // Y() invoked the first time

When we execute X() and Y(), we are essentially executing the inner function.

Let us examine step-by-step what happens when X() is executed the first time:

- Variable a is created, and its value is set to 20.

- JavaScript now tries to execute a + b. Here is where things get interesting. JavaScript knows that a exists since it just created it. However, variable b no longer exists. Since b is part of the outer function, b would only exist while the outer() function is in execution. Since the outer() function finished execution long before we invoked X(), any variables within the scope of the outer function cease to exist, and hence variable b no longer exists.

How does JavaScript handle this?

Closures

The inner function can access the variables of the enclosing function due to closures in JavaScript. In other words, the inner function preserves the scope chain of the enclosing function at the time the enclosing function was executed, and thus can access the enclosing function?s variables.

In our example, the inner function had preserved the value of b=10 when the outer() function was executed, and continued to preserve (closure) it.

It now refers to its scope chain and notices that it does have the value of variable b within its scope chain, since it had enclosed the value of b within a closure at the point when the outer function had executed.

Thus, JavaScript knows a=20 and b=10, and can calculate a+b.

You can verify this by adding the following line of code to the example above:

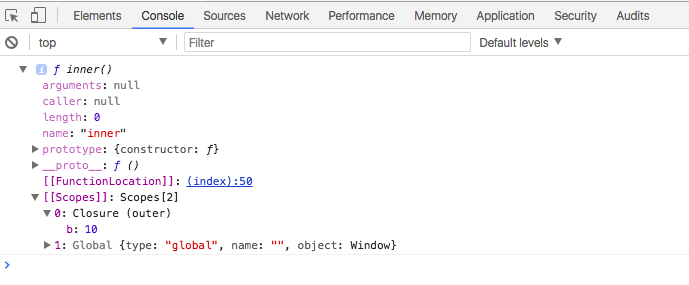

function outer() {var b = 10; function inner() { var a = 20; console.log(a+b); } return inner;}var X = outer(); console.dir(X); //use console.dir() instead of console.log()

Open the Inspect element in Google Chrome and go to the Console. You can expand the element to actually see the Closure element (shown in the third to last line below). Notice that the value of b=10 is preserved in the Closure even after the outer() function completes its execution.

Variable b=10 is preserved in the Closure, Closures in Javascript

Variable b=10 is preserved in the Closure, Closures in Javascript

Let us now revisit the definition of closures that we saw at the beginning and see if it now makes more sense.

So the inner function has three scope chains:

- access to its own scope ? variable a

- access to the outer function?s variables ? variable b, which it enclosed

- access to any global variables that may be defined

Closures in Action

To drive home the point of closures, let?s augment the example by adding three lines of code:

function outer() {var b = 10;var c = 100; function inner() { var a = 20; console.log(“a= ” + a + ” b= ” + b); a++; b++; } return inner;}var X = outer(); // outer() invoked the first timevar Y = outer(); // outer() invoked the second time//end of outer() function executionsX(); // X() invoked the first timeX(); // X() invoked the second timeX(); // X() invoked the third timeY(); // Y() invoked the first time

When you run this code, you will see the following output in the console.log:

a=20 b=10a=20 b=11a=20 b=12a=20 b=10

Let?s examine this code step-by-step to see what exactly is happening and to see closures in Action!

var X = outer(); // outer() invoked the first time

The function outer() is invoked the first time. The following steps take place:

- Variable b is created, and is set to 10Variable c is created, and set to 100Let?s call this b(first_time) and c(first_time) for our own reference.

- The inner function is returned and assigned to XAt this point, the variable b is enclosed within the inner function scope chain as a closure with b=10, since inner uses the variable b.

- The outer function completes execution, and all its variables cease to exist. The variable c no longer exists, although the variable b exists as a closure within inner.

var Y= outer(); // outer() invoked the second time

- Variable b is created anew and is set to 10Variable c is created anew.Note that even though outer() was executed once before variables b and c ceased to exist, once the function completed execution they are created as brand new variables.Let us call these b(second_time) and c(second_time) for our own reference.

- The inner function is returned and assigned to YAt this point the variable b is enclosed within the inner function scope chain as a closure with b(second_time)=10, since inner uses the variable b.

- The outer function completes execution, and all its variables cease to exist.The variable c(second_time) no longer exists, although the variable b(second_time) exists as closure within inner.

Now let?s see what happens when the following lines of code are executed:

X(); // X() invoked the first timeX(); // X() invoked the second timeX(); // X() invoked the third timeY(); // Y() invoked the first time

When X() is invoked the first time,

- variable a is created, and set to 20

- the value of a=20, the value of b is from the closure value. b(first_time), so b=10

- variables a and b are incremented by 1

- X() completes execution and all its inner variables ? variable a ? cease to exist.However, b(first_time) was preserved as the closure, so b(first_time) continues to exist.

When X() is invoked the second time,

- variable a is created anew, and set to 20 Any previous value of variable a no longer exists, since it ceased to exists when X() completed execution the first time.

- the value of a=20the value of b is taken from the closure value ? b(first_time)Also note that we had incremented the value of b by 1 from the previous execution, so b=11

- variables a and b are incremented by 1 again

- X() completes execution and all its inner variables ? variable a ? cease to existHowever, b(first_time) is preserved as the closure continues to exist.

When X() is invoked the third time,

- variable a is created anew, and set to 20Any previous value of variable a no longer exists, since it ceased to exist when X() completed execution the first time.

- the value of a=20, the value of b is from the closure value ? b(first_time)Also note that we had incremented the value of b by 1 in the previous execution, so b=12

- variables a and b are incremented by 1 again

- X() completes execution, and all its inner variables ? variable a ? cease to existHowever, b(first_time) is preserved as the closure continues to exist

When Y() is invoked the first time,

- variable a is created anew, and set to 20

- the value of a=20, the value of b is from the closure value ? b(second_time), so b=10

- variables a and b are incremented by 1

- Y() completes execution, and all its inner variables ? variable a ? cease to existHowever, b(second_time) was preserved as the closure, so b(second_time) continues to exist.

Concluding Remarks

Closures are one of those subtle concepts in JavaScript that are difficult to grasp at first. But once you understand them, you realize that things could not have been any other way.

Hopefully these step-by-step explanations helped you really understand the concept of closures in JavaScript!

Other Articles:

- A quick guide to ?self invoking? functions in Javascript

- Understanding Function scope vs. Block scope in Javascript

- How to use Promises in JavaScript

- How to build a simple Sprite animation in JavaScript