L?INFERNO (1911) ? Francesco Bertolini, Adolfo Padovan, Giuseppe de Liguoro

L?INFERNO (1911) ? Francesco Bertolini, Adolfo Padovan, Giuseppe de Liguoro

Note: This is the sixty-first in a series of historical/critical essays examining the best in film from each year. Essentially, I am watching films from the beginning of cinematic history that interest me and/or hold some critical or cultural impact. My personal, living list of favorites is being created at Mubi, showcasing five films per year. All this being explained, what follows is an examination of my favorite 1911 film, L?INFERNO, directed by Francesco Bertolini, Adolfo Padovan, and Giuseppe de Liguoro.

I?m an atheist, but I remember being profoundly scared by Dante Alighieri?s Inferno, the first part of his epic poem Divine Comedy. That?s how potent his writing was; although the poem comes out encyclopedic in its explanation of the layers of Hell, the descriptions of the torture are anything but boring. And part of the reason why I was so scared, as an agnostic young boy, was that some of the deeds that warranted this extremely violent punishment didn?t seem?that bad? Certainly, I could see some of myself in gluttony, and at a time when I wasn?t quite sure of the implications, lust. And as an unbaptized child, even Limbo seemed like an unfair fate. With my overactive mind and early onset anxiety, I started to wonder if my deeds would land myself in the Inferno.

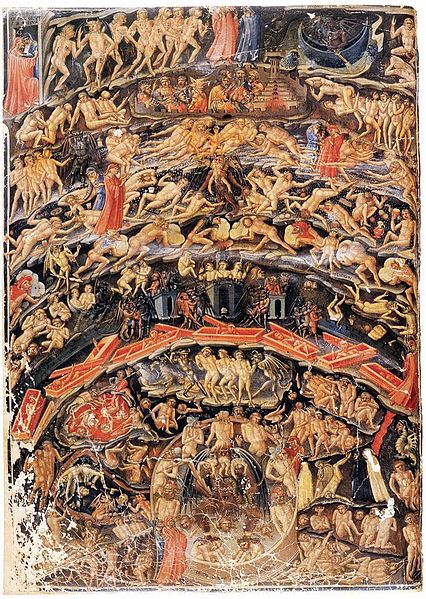

?Inferno, from the Divine Comedy by Dante? by Bartolomeo Di Fruosino

?Inferno, from the Divine Comedy by Dante? by Bartolomeo Di Fruosino

I grew out of that religious fear. But I also grew to appreciate the language of Dante, translated and so impure as it was. Great art elicits a potent reaction, and that?s just what Inferno did. Somehow, nearly impossibly, a 1911 Italian film was able to contain very strong shades of Inferno?s impact, if not perfectly translating it.

Part of that strength stems from L?INFERNO?s epic scope. It?s over 60 minutes long, a feature-length film at a time when very few existed. Indeed, THE STORY OF THE KELLY GANG (1906) was the world?s first, and the last significant one before L?INFERNO. And it only ran just over 40 minutes. L?INFERNO was also Italy?s first feature-length film, and its directorial triumvirate (Francesco Bertolini, Adolfo Padovan, and Giuseppe de Liguoro) would also make a feature-length adaptation of Homer?s Odyssey the same year. But besides its length, L?INFERNO has tremendous production value that, at times, can look cheesy through a modern lens. But L?INFERNO?s aesthetic appeal is never boring, and in fact, it always looks otherworldly. The film is a compelling, immersive dive into Hell.

Not a whole lot of information about Bertolini, Padovan, and de Liguoro is readily available. Bertolini appears to have directed just a few films starting with L?INFERNO through 1922. Padovan?s credits only span 1911 productions for Milano Films, the Italian studio that also seemed to peak with its two earliest literary adaptations. But he was a literary and philosophy scholar, and after just that short year in the film industry, he returned to that work. De Liguoro may have had the greatest legacy in show business. Each of his sons were a director and actor, respectively, and had the most prolific filmmaking career of the three.

But what would have brought three different men of such different persuasions together to direct a film? Well, as strange as it would be today, a three-person directorial credit was not quite uncommon by 1911. The demarcation of directorial responsibilities were not quite set in stone. I can see Padovan bringing the adaptation legwork to the movie, in a role we might now consider a screenwriter. De Liguoro may have directed the acting, having had that training, while Bertolini may have been in charge of the technical aspects. This is all conjecture, but considering the diversity in their stories, not unfounded, as other films? directing credits were shared in this manner at the time. Oh, and of course, L?INFERNO was at least three times as long as even the most lengthy and ambitious shorts, so it makes sense that it had three times the directors.

Regardless of who brought it to the screen, L?INFERNO?s greatest achievement is the sumptuousness of its mise en scne. There is certainly a prodigious amount of horrific and morbid images paraded throughout the film, but the rendering of costumes, special effects, and set design create an awe-inspiring, ethereal quality. The pale, naked bodies of men and women adorn every layer of hell, wriggling in agony. Although the men wear loincloths, and very few glimpses of full frontal female nudity are seen, there is a lot of fetishistic energy in L?INFERNO, down to the design of the loincloths that seem to create an exaggerated phallus rather than obscure one.

This costuming also makes the various humanoid creatures Dante and his companion Virgil encounter notable experiences in themselves. Pluto, various demons, and, as mentioned, the hordes of sinners themselves are, quite simply, visually interesting denizens, only augmented by their surroundings and situations. The harpies in the ?Wood of the Suicides,? and the decrepit forest we find them in, are reminiscent of Fritz Lang?s DIE NIBELUNGEN films (1924). This comparison to a film that was ahead of its time even 13 years later is a massive compliment.

DIE NIBELUNGEN: SIEGFRIED (1924) ? Fritz Lang

DIE NIBELUNGEN: SIEGFRIED (1924) ? Fritz Lang

The more elaborate creatures, the ones on four legs like Cerberus, look like a lot of the ?school play? costumes typical of the era; that is, they look like people on all fours in a silly animal outfit. And I love them as well.

Part of the strength of these otherwise cheesy production elements are the sets. The expansive, craggy mountains and wide, deep bodies of water the pair encounter are certainly not as large as they appear. But the filmmakers were able to create a really impressive illusion of depth and size with a mixture of artificial sets (I use this as a positive term; I love the craft of the artifice in film) and on-location shots.

?The Inferno, Canto 34? by Gustave Dor

?The Inferno, Canto 34? by Gustave Dor

The final scene takes place in the ninth, frozen circle of Hell. It may be the most incredible location of L?INFERNO. The whole film?s look was based on the incredible paintings of Gustave Dor, a 19th-century artist whose literary works are actually the basis for a lot of the visuals of filmic adaptations, and his visualization of the ninth circle is notably brought to life at the end. The image of segmented ice cubes with the treacherous sinners? heads popping out is an incredible one. And of course, perhaps the film?s most iconic moment, is jaw-dropping.

The special effects of L?INFERNO are insane. Lucifer is massive, wings stretching out behind him in front of a black void. And when Dante and Virgil come upon him, he?s devouring Brutus and Gaius in a disgusting display of double exposure and scale manipulation. This scale manipulation was also profoundly illustrated the scene prior, when a giant grabs the pair and brings them down to the last circle. The two are shown standing next to the giant?s massive legs; the seam in the film is quite clear, but it?s impressive nevertheless. A man carrying his own head in his hands in another part of the film is much more convincing, and therefore haunting.

The second circle of Hell, which belongs to the lustful, is an especially standout experience. The nude lovers are buffeted about by winds as their punishment, which is visualized in the film by an endless stream of lazily churning crowds of human flesh, endlessly swinging around in a fucked up, double exposure mobile of naked people. Another technical achievement is a bit less impressive to those used to film structure of the past, well, 115 years, but L?INFERNO also features a few flashback sequences. As in the source material, Dante stops to converse with at least one sinner in each circle, and the story of a few are told in flashback. It?s an important editing innovation that had not been achieved before.

Speaking of those interactions with sinners: Dante?s treatment of them, as in the poem, range from sympathetic to cruel. These interactions are usually uncomfortable in some manner. L?INFERNO is also one of the few films to depict Muhammad. But as in the poem, the depiction isn?t exactly flattering; he?s in the eighth circle, for fraud.

Full film

L?INFERNO is an outstanding visual and storytelling achievement, a film that was able to capture some of the manic, tortuous, and bizarre imagery, themes, and energy of an incredibly complex masterwork, silently and in about 70 minutes no less. It was simply one of the best films ever created when it was released in 1911, and therefore, the best of the year. It certainly stands as one of the great achievements from the ?forgotten era? between the widely known years of A TRIP TO THE MOON (1902) and THE GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY (1903) and the ?birth of modern cinema? that was THE BIRTH OF A NATION (1915). L?INFERNO is metal as fuck and deeply evocative of complex psychology and philosophy, a blend of quasi-blockbuster and ?arthouse? film that leaves me feeling vindicated in my original fear of Dante?s Inferno. Because if this is what Hell is like, I don?t want to be sentenced to live there for all eternity. But I definitely want to experience it, walk through it and see the depths of human misery and cruelty. When I reach Paradise, it?ll feel only all the more deserved.

Make sure to catch up on and keep up with all of my essays on my favorite films here.