Last week, the Joseph Smith Papers published the records of Joseph Smith?s legal trials. Today, it added the printer?s manuscript of the Book of Mormon and pictures of the seer stone Joseph used during the translation. The two are not unrelated.

A common anti-Mormon accusation is that Joseph was convicted of fraud for glass-looking in his first, 1826 trial. (That is, three years after his first vision of the Angel Moroni, and one year before Moroni gave him the Golden Plates.)

The first account of this trial, by Emily Pearsall, the niece of the trial judge, was published in 1873 in Frazer?s Magazine. A separate account was published in 1877 by William Purple, who was scribe for the trial.

Mormon apologists contended for years that these accounts were fictional: that there was no 1826 trial, and if the Pearsall and Purple accounts had any basis in fact it must have been Smith?s 1830 trial for vagrancy. But in 1971 the original bills were discovered for the fees charged by the judge and constable in the trial, corroborating the date and substance of the trial. Scans and transcriptions of these bills are what were recently made available from the Joseph Smith Papers.

The JSP does not include the Pearsall and Purple accounts, but Russell Anderson?s FairMormon article includes both, arranged by content. There is broad agreement on the main point: Smith was charged with defrauding Josiah Stowell by charging him money for ?glass looking,? or using his stone to find treasure in a vision.

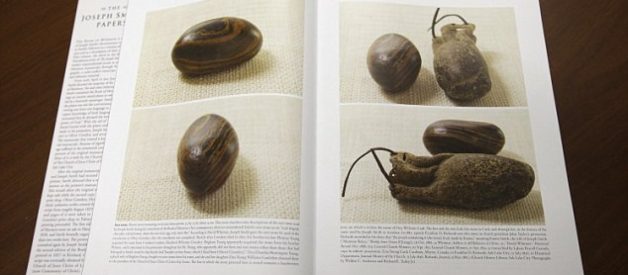

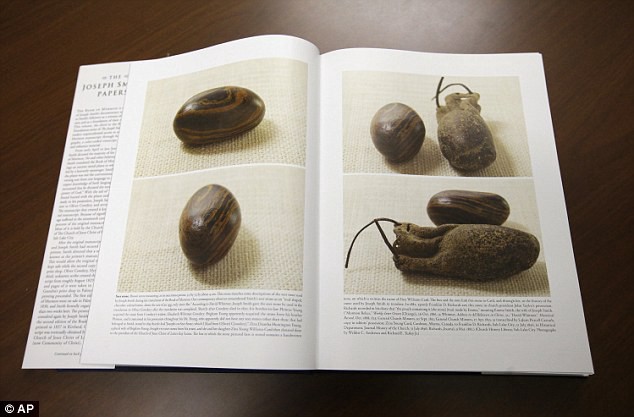

The description of the stone in the Purple account matches the pictures that were published this week for the first time:

On the request of the Court, he exhibited the stone. It was about the size of a small hen?s egg, in the shape of a high-instepped shoe. It was composed of layers of different colors passing diagonally through it. It was very hard and smooth, perhaps by being carried in the pocket.

Both accounts agree that Stowell had confidence in Smith?s glass-looking abilities. Here?s the Purple account:

Neeley soberly looked at the witness, and in a solemn, dignified voice said: ?Deacon Stowell, do I understand you as swearing before God, under the solemn oath you have taken, that you believe the prisoner can see by the aid of the stone fifty feet below the surface of the earth; as plainly as you can see what is on my table?? ?Do I believe it?? says Deacon Stowell; ?do I believe it? No, it is not a matter of belief: I positively know it to be true.?

And Pearsall:

[Stowell] says that he positively knew that the prisoner could tell, and professed the art of seeing those valuable treasures through the medium of said stone ? that he never deceived him; ? [and he] had the most implicit faith in prisoner?s skill.

While the Pearsall account concludes that ?the Court finds the defendant guilty,? both Anderson and Gordon Madsen (writing in BYU Studies) find this unlikely, for different reasons. I find Madsen particularly convincing:

- ?Only Josiah Stowell had any legal basis to complain, and he was not complaining.? [Madsen?s emphasis]

- ?The statute required the justice upon conviction to commit the defendant? to hard labor,? which would have been present on both the judge?s and constable?s bills.

- ?I believe [the statement of guilt] is an afterthought supplied by whoever subsequently handled the notes and is not a reflection of what occurred at the trial. This view is buttressed by the curious fact that all through the Pearsall notes, Joseph Smith is referred to only as the ?prisoner.? Then for the first time in this final sentence he is called ?defendant.?? (Pearsall?s account was copied by Charles Marshall before publication, so at least Marshall as well as Pearsall had the opportunity to add a more ?interesting? ending.)

But even if Stowell was not complaining, was he in fact defrauded? That?s less clear. Purple and Pearsall both describe the testimony of Stowell?s employee Jonathan Thompson. I will only quote Purple, but Pearsall?s matches closely. (Again, the full accounts are available in an appendix of Anderson?s article.)

Smith had told the Deacon [i.e., Stowell] that very many years before a band of robbers had buried on his flat a box of treasure, and as it was very valuable they had by a sacrifice placed a charm over it to protect it, so that it could not be obtained except by faith, accompanied by certain talismanic influences. So, after arming themselves with fasting and prayer, they sallied forth to the spot designated by Smith. Digging was commenced with fear and trembling, in the presence of this imaginary charm. In a few feet from the surface the box of treasure was struck by the shovel. on which they redoubled their energies, but it gradually receded from their grasp. One of the men placed his hand upon the box, but it gradually sunk from his reach, After some five feet in depth had been attained without success, a council of war, against this spirit of darkness was called, and they resolved that the lack of faith, or of some untoward mental emotions was the cause of their failure.

The concept of treasure that would slip away if the spirits guarding it were not properly placated was common in this 19th century environment. (Smith would later chronicle a similar belief in the Book of Mormon.) But from a modern perspective, I see three possibilities:

- God really did show Smith these treasures in his stone, but allowed the guardian spirits to prevent recovery by Stowell?s party

- Smith had an excellent imagination and convinced himself as well as others that he saw treasure in his stone

- Smith deliberately defrauded Stowell

We can rule out the first, since under Mormon theology neither God nor the spirits of the dead act in such a manner. And most evidence that unmistakably portrays Joseph as knowingly taking advantage of his followers? gullibility are from distinctly hostile sources. The second option seems to me the most likely.

While the trial raises legitimate questions about the relationship between glass-looking and Smith?s religious work, particularly the Book of Mormon translation, Smith was almost certainly not officially found guilty.

Further reading

- Full primary sources with transcriptions, including several sources I omitted for brevity

- Dan Vogel?s analysis of the trial, arriving at a somewhat different conclusion