12-year-old Johnny Gosch

12-year-old Johnny Gosch

The Johnny Gosch case is easily one of the most complicated out there. There have been so many developments over the years ? not to mention theories ? that the only way to do the story justice is to create a series, instead of a single post.

It is also important to mention that there seem to be multiple versions of events posted across the Internet. My goal is to be as accurate as possible, but in some cases, the information published here may be slightly different from other outlets.

If you?re looking for a missing person story that makes you scratch your head in confusion, look no further than the story of Johnny Gosch. If you?re a true crime fan, you probably already know this story, as it has been the subject of documentaries, books, and more news stories than you can count.

This incident took place in the early 1980s, so let me paint a picture of what childhood was like during that decade, for those of you too young to remember a time when your mom couldn?t text you 15 times a day.

See, I was a child in the 1980s, and people didn?t worry much about things like pedophiles. Few people even knew what the word meant. Certainly, no one believed that organized pedophile rings existed. I don?t know if it was a simpler time, so much as a more naive one. Evil was lurking, but it lurked mostly out of sight.

A typical summer day meant going outside to play in the morning and, often, not coming home until the sun started setting, your mom called your name, or you saw the porch light flicker on.

People felt safer then, and even though most kids got the ?stranger danger? talk from their parents or school, there was vastly less supervision.

But feeling safe and being safe are two different things. Twelve-year-old Johnny Gosch lived in what his parents believed to be a safe, upper-middle-class area of West Des Moines, Iowa, but danger literally lurked around the corner, and the young boy?s kidnapping forever erased the false sense of safety in that town, as well as the rest of the country.

A Seemingly Innocent High School Football Game

On Friday, September 3, 1982, the Gosch family settled into cramped high school stadium seats to watch their older son play football.

Johnny wanted a snack, so his parents gave him a few bucks and sent him to the concession stand.

When it seemed like Johnny was taking longer than usual to return, his father, John Sr., went looking for the boy. He found him underneath the bleachers, talking to a police officer. He motioned for Johnny to come back and join them in the stadium.

Nothing seemed strange about the encounter. After all, it?s fairly common for a police officer to be present at football games and other crowded school sporting events, just to make sure nothing gets out of hand. Most people wouldn?t be alarmed to see their child talking to an officer. If anything, it would be comforting and reassuring. And as the family walked out of the stadium at the end of the game, Johnny commented that he might consider becoming a police officer when he got older.

Nothing bizarre. Nothing frightening.

Not at the time, anyway. In hindsight, the interaction between Johnny and the cop would set off alarm bells in the minds of Leonard John Gosch Sr. (John Sr.) and Noreen Gosch.

An Average Sunday Morning

September 5, 1982, was your average Sunday morning. All across the United States, youngsters were assembling and rubber-banding newspapers and preparing to deliver them to houses, including Johnny Gosch.

Johnny was already readying his papers before the sun came up. The only unusual aspect of that morning was the fact that Johnny?s father didn?t accompany his son on his paper route like he normally did.

The previous night, Johnny had asked if he could do his route on his own, but his mother said no. It?s not clear how or why Johnny made it out the front door without his dad the next morning, but that is a part of one of the twisted theories behind Johnny?s kidnapping that we will explore later on.

By 7 a.m., perturbed neighbors started calling the Gosch home to complain that they hadn?t received their paper yet. At first, Johnny?s parents thought maybe their son had overslept, so they checked his room, but he wasn?t there. John Sr. went out to find his son and found the boy?s abandoned wagon, full of undelivered newspapers, about two blocks from home. The rubber bands Johnny used to hold the newspapers together were left undisturbed.

To the average observer, it appeared that Johnny had just walked away. There were no outward signs of a crime, and the police used this fact to dismiss important details, like witness statements, that most certainly indicated that a crime had been committed.

The family?s dachshund, which typically accompanied Johnny on his route, eventually returned home on its own.

By all accounts, Johnny wasn?t the type of kid to run off and leave his dog and his deliveries behind. Where would he have gone? Kids aren?t out playing at 5:45 a.m. on a Sunday. Besides, Johnny didn?t have a paper route just for fun. He was saving his money to purchase a dirt bike, so it made no sense for him to skip his route and risk getting in trouble.

John Sr. and Noreen knew immediately that something was wrong. John Sr. came home and told his wife that their son was nowhere to be found, and Noreen dialed the police while her husband went to deliver the papers.

Some people question why John Sr. went to deliver Johnny?s papers instead of immediately helping search for his son. This doesn?t sound too out-of-the-ordinary to me, though. Imagine trying to organize a search party for your son with the phone ringing off the hook about undelivered newspapers! Not only that, but they had to keep the phone line open, in case Johnny, or perhaps his kidnapper, tried to call.

According to Noreen, it took the police 45 minutes to arrive at the Gosch home, even though the police department was located about 10 blocks away, and they had already dubbed Johnny a runaway.

Witnesses

A 1979 Ford Fairmont similar to the one that approved Johnny Gosch and other paperboys on the morning of September 5, 1982.

A 1979 Ford Fairmont similar to the one that approved Johnny Gosch and other paperboys on the morning of September 5, 1982.

When the Gosches spoke to their neighbors, it became clear to them that Johnny had been kidnapped. Multiple people reported seeing a man in a blue Ford Fairmont talking to Johnny. One neighbor, a retired lawyer named John Rossi, said he saw Johnny giving directions to the man in the car. When Johnny asked Rossi if he could help the man with directions, the driver made a speedy U-turn and tore out of the neighborhood, blowing through a stop sign in the process.

John Rossi later underwent hypnosis to remember more details about the man, but the results were never made public.

Johnny told his fellow paperboys that the man in the Ford Fairmont creeped him out ? and rightly so ? and that he was getting out of there.

In 2010, Noreen Gosch told WHO-TV:

The guy shut off his engine, opened the passenger door, and swung his feet out on the curb right where the boys were assembling their newspapers. And he started talking about, ?Where?s 86th Street?? Johnny turned to Mike and said, ?I?ve got my papers loaded in the wagon. I?m scared. I?m getting out of here. I?m gonna head home.?

The man pulled the door shut and started up the engine, but before he left, he reached up and flicked the dome light three times. Then he pulled out and left.

Noreen believes the driver flicked the dome lights three times to signal someone else, and one of the paperboys reported that he saw a tall man walk out from between a couple of houses after the paperboys were approached by the man in the vehicle. Noreen is convinced that this was the person who snatched her son.

It was later revealed that the vehicle displayed a Nebraska license plate, which became increasingly important as time went on.

A Sorry Excuse for a Police Department

What would you do if your child went missing and was, perhaps, kidnapped? Most parents would immediately call the police, and the Gosches were no different.

Sure, we had less supervision back then, but if you didn?t reappear when you were supposed to, it raised red flags. I once got home five minutes after I heard my mother call for me, and when I walked in the door, she was hysterical and had the phone in her hand.

Johnny had been walking his neighborhood, tossing papers into people?s yards, for over a year. His movements and actions had become routine. Until that day, he had always delivered his papers on time. The Gosches had never received a single, solitary call about late deliveries.

In 1982, the police responded to nearly all child disappearances the same way: ?I?m sure he will turn up on his own.? There is no longer a mandatory waiting period before launching a search for a child, thanks to legislation proposed by the Gosches, but that remains the attitude among many in law enforcement.

But John Sr. and Noreen were met with a shocking level of indifference by the West Des Moines Police Department (WDMPD).

According to then-rookie cop Lt. Jeff Miller, the police starting hunting for the boy immediately.

They went ahead and called in the staff. The troopers. They called in detectives. Reserves. Contacted Polk County Sheriffs. The State Patrol. At that point, they did a door-to-door canvass of that neighborhood trying to find someone who saw something of Johnny.

The police also searched the nearby woods, but were still unwilling to consider the possibility of child abduction, so the search was a lazy one, at best. And when locals tried to help, police stymied their efforts.

Approximately 20 volunteers gathered at a local park to help search for Johnny. According to Noreen, they were encountered by Orval Cooney, the alcoholic police chief who would later leave the department in disgrace. He drunkenly stood atop a picnic table and shouted through a megaphone that the searchers should go home because Johnny was ?just a damn runaway.?

How God-awful were they? When the Gosches proposed placing missing child posters of Johnny in the Hall of Law in 1983, they were given a firm ?no.?

Noreen explained:

We approached them to ask if we could bring out a quantity of missing posters (8 x 10), hoping someone might remember something and call with info. They refused, saying it would be a ?downer for fairgoers.?

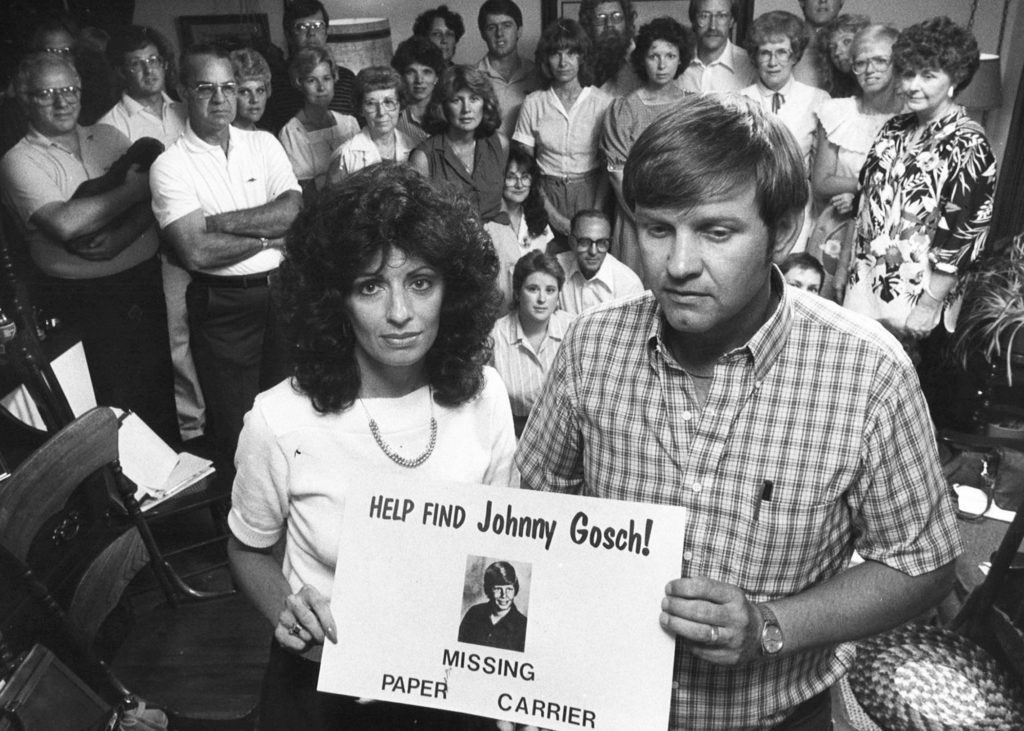

Noreen and John Gosch Sr. ? Source: Iowa Cold Cases

Noreen and John Gosch Sr. ? Source: Iowa Cold Cases

In the years that followed, the investigation would take several sick and terrifying turns, launching conspiracy theories and speculation about the mental health and authenticity of Noreen Gosch.

But as you will soon read, there are too many coincidences behind those conspiracy theories for them to be ignored and dismissed.

Moreover, the disappearance of more boys would lend credence to the Gosches? belief that their son was abducted.

Eugene Martin ? Source: Iowa Cold Cases

Eugene Martin ? Source: Iowa Cold Cases Marc Allen ? Source: Iowa Cold Cases

Marc Allen ? Source: Iowa Cold Cases