My Japanese high school students try explaining to me why pastel drawings of depression and death are cute.

It was the second week of summer vacation in Japan, and I was trying to stay awake while editing a student?s presentation, my chair as casually close to the A/C as I could manage. My brain was on autopilot, scanning for incorrect spellings and misused Engrish, when I came across a word that broke the doldrums of August. I read it, reread it, and finally looked up at the student waiting patiently for me to finish reading her script. ?What is ?Yamikawaii??? I asked. I was met with a wide smile, followed almost immediately by a puzzled expression; clearly, this was something awesome, but hard to explain. ?Cute, but mental health,? she managed to surmise, which, frankly, wasn?t going to cut it. She struggled with words a bit longer, then finally asked if she could just show me on her phone.

Pink hearts, pink backgrounds, pretty fonts? all beautifully juxtaposed with knives, guns, dead people, and depressing messages. A sudden gust of Myspace nostalgia hit me, but this seemed legitimately dark. Back in my day, we kept it contained to sullen gifs of Tom Felton, with some Linkin Park lyrics thrown on for good measure. Our Myspace pages were edgy and vomit-inducing, because we were fourteen and trying to be deep, but the topics were relatively tame. Yet this was different. This was bright, vivid, and aesthetically pleasing, but filled with gore, suicide imagery, and disturbing commentary. My student pointed to a particular image of a girl impaled on a merry-go-round and exclaimed ?????!? (or kawaii, meaning cute in Japanese). Hang on. This isn?t Pikachu dressed as a detective. How in the world was this kawaii?

The cute and colorful picture my students showed me.

The cute and colorful picture my students showed me.

We scrolled through numerous examples, and no matter which picture I selected, the student would respond as if it was a baby wearing an overstuffed winter coat. Girl pointing a gun to her neck? Kawaii. A bunny with dead eyes holding a noose? Kawaii. I called over another student and pointed at an image of a girl hiding a knife behind her back while her ?fake? friends chatted in front of her. ?Oh, kawaii!? We were clearly at a disconnect. The students showed me more examples, but I could see that this was going to require a bit more research to understand.

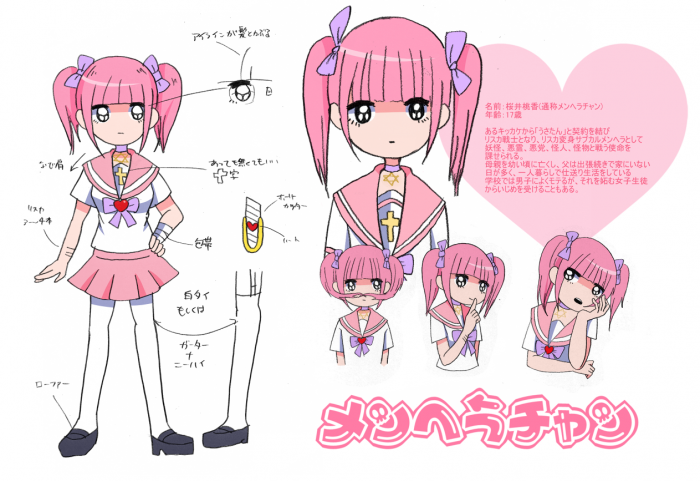

Yamikawaii is written with the kanji (or Chinese character) ?, meaning illness or sickness, which is most commonly found in the word for hospital, by?in (??). Another way to interpret the kanji is mental illness, or menhera, and this is where our strange subculture finds its name. My students explained to me that Yamikawaii is a Japanese subculture originating in Harajuku, a district in Tokyo notorious as a hub for youth fashion and counterculture. The subculture is a sort of anti-kawaii, revolving around the traditional pastels and cutesy-ness of traditional kawaii culture, contrasted with messages and imagery surrounding depression, social anxiety, and suicide, among other colorful mental issues. The movement has tons of followers and fan-art, an unofficial mascot, idol groups cashing in, and even a couple of Harajuku stores (where else) dedicated to the trend.

Menuhera-Chan, complete with slit wrists.

Menuhera-Chan, complete with slit wrists.

The thing is, Yamikawaii should not have surprised me as much as it did. It instantly made me think of the emo trend from when I was a teenager, but with a different, cutesy take. Not to mention, I have stumbled upon many a DeviantArt page dedicated to strange and terrifying fan art, so none of the images were too shocking. This is also not the strangest kawaii subculture out of Harajuku that I?ve seen. Kowakawaii (scary kawaii) is all about blood, eyes out of sockets, and other grotesque imagery. Yumekawaii (dream kawaii) is a mix of fairy-tale unicorns, bright pastels, and a splash of yami (this time, meaning ?darkness?) represented by bandages, needles, you name it. These trends all have anti-establishment, or anti-cuteness, in common, and it?s no surprise they have dedicated and overlapping fan bases.

Still, I found myself bothered. My students had reacted to examples of Yamikawaii the same way they would react to anything kawaii. I tested this thoroughly, trying to spot a difference. Picture of me as a baby? ?Kawaii!? An adult and kid version of Master Chief? ?Kawaii!? Picture of a schoolgirl with pink hair, bandaged wrists, holding a knife? ?Kawaii!? What if I covered the knife? Still, ?Kawaii!?. It seemed that no matter what I did or how insane this seemed to me, the students thought that cute was cute, regardless of subject matter.

That?s where the disconnect lies. For me, kawaii means cute, and cute things are easily definable. Adorable, small, huggable, pretty; any stuffed animal or baby cousin is cute. Red Pandas after a snowfall are the cutest thing on the planet. When you add in an element of shock, such as with Yamikawaii, the picture changes. The cuteness becomes ironic, and the focus becomes the message the artist is trying to convey. A cry for help, repressed negative desires, a reflection on popular culture. This is what I see. Either that or the start of a good zombie game. Take the creepy cuteness, add a slow music-box loop and some distorted laughter, and you have a summer top-seller waiting to happen.

?Let?s dream sweetly together.?

?Let?s dream sweetly together.?

I can?t help but wonder if there is a real issue buried beneath the pink frilly facade and dead unicorns. When you live in any country long enough, you begin to notice the cracks, even in an otherwise streamlined society like Japan. In the aforementioned country?s case, the cracks seem to be the collective acknowledgment (or lack thereof) of mental health. While no country has been able to perfectly address the issue of mental health in society, discussion in Japan seems to be relatively non-existent. Maybe it is this lack of social recognition that drives my students? reaction to Yamikawaii; they simply don?t recognize the seriousness of the underlying message. Or maybe there is no underlying message, and these works of art are just cashing in on a trend. Regardless, the issue of why Yamikawaii exists, and its connection to Japan?s social perception of mental health, deserve far more than a thousand words from a jaded undergrad.

In the end, it all comes back to the reactions of my students, and of children around Japan that are influenced by the subcultures of Harajuku. Maybe they think it?s cute and connect with it because the trend is highlighting their true feelings. Maybe I?m making a big deal out of passing interest. Maybe my students see the same things as me, but can?t express it. What they can, and do, express, is that unrelenting joy of seeing something that appeals directly to your heart. KAWAII!

Originally published in AJET Connect Issue #52.