(Editor?s note: This article was written jointly by siblings Julie Devaney Hogan and Erik Devaney)

Photo by Oliver Pacas on Unsplash

Photo by Oliver Pacas on Unsplash

?Boston? and ?racism? have become near synonyms. Whether it?s that infamous line from Martin Scorcese?s The Departed (?You?re a black guy in Boston. You don?t need any help from me to be completely f****d.?), or Roy Wood Jr.?s Daily Show expos, ?How Racist Is Boston??, or Saturday Night Live?s Michael Che calling out Boston as ?the most racist city? he?s ever been to, it?s clear that something is rotten in Beantown.

But as Reverend Irene Monroe highlights in her commentary ?Boston?s Racist Past Haunts Its Present,? racism in Boston is by no means a new phenomenon, with the busing crisis of the 1970s standing out as perhaps the most egregious episode. To quote Reverend Monroe:

The ugliness that surrounded the busing controversy is the most prominent example, but there are others that reverberate around the city today. I?m thinking of Charles Stuart, who blamed a black homeless man of killing his pregnant wife to try to cover up his crime. More recently, there was the Henry Louis Gates, Jr., episode. The esteemed Harvard professor, who is black, was arrested trying to open his door. The police thought he was a burglar.

Of course, if you stopped a white Bostonian on the street and asked about racism, as Roy Wood Jr. did, you?d likely hear some variation of, ?We?ve moved past it. Racism is over now in Boston. It doesn?t exist.? One person even claimed that perceptions of Boston being racist stem from the fact that our sports teams are so good.

Yikes.

To our fellow white Bostonians: We clearly have a lot of work to do.

The murder of George Floyd and the widespread conversations about race that are finally happening after a decade of watching black people die have led us to a crucial inflection point. We can?t keep silent, as we have for so long ? especially not when we see so many of the white people around us perpetuating racism (sometimes purposefully, sometimes inadvertently) and falling into the same traps we did.

Our goal here isn?t to shame, it?s to share what we?ve been learning after years of screwing it up. And to be clear, we?re still trying to figure it out. This is work that will never be finished. So while we don?t profess to have all the answers, we have struck upon three things that we think will help our white friends and family members (and ourselves) become better allies to Black people in a place with one of the nation?s worst reputations when it comes to racism. (Note: At the end of this article we?ve included several resources and action items for white people who are ready to help make this change a reality.)

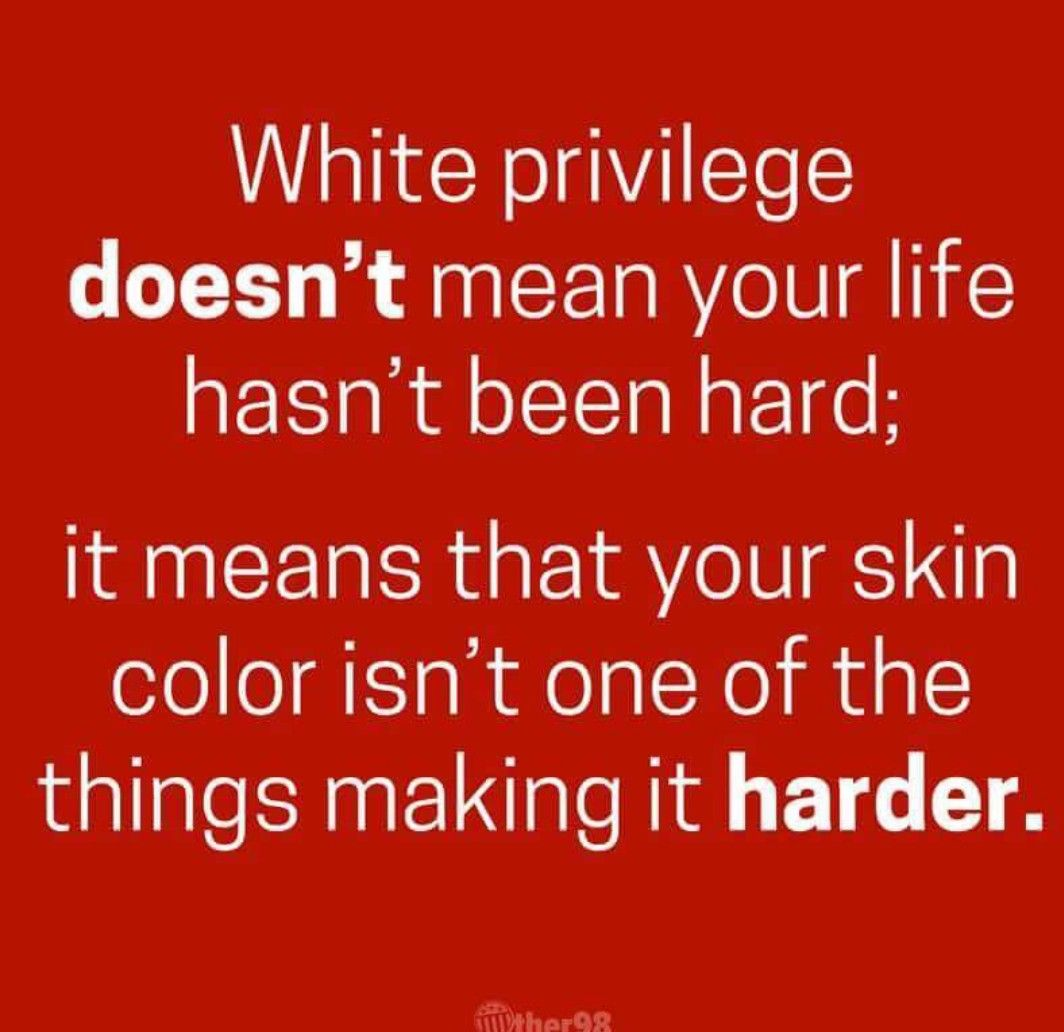

1. You don?t have to grow up ?privileged? to have white privilege.

If you grew up in the Boston area, you?re likely familiar with the term ?W Towns.?

W Towns ? like Weston, Wellesley, and Winchester ? are some of the area?s most affluent communities. The houses there are monstrous. The town squares are quaint and picturesque. And the public school systems are impeccable (yet many in these communities still opt to send their kids to private schools anyway).

However, there?s another set of ?W Towns? in the Boston area that often get overlooked. These W Towns are blue-collar, working-class communities ? like Waltham, Wilmington, and our home town, Woburn.

Growing up in one of these blue-collar, predominantly white communities, we believed at an early age that the people in the affluent W Towns were a privileged bunch, while we ourselves had no privilege.

And this is how our white privilege blind spots ? and the blind spots of so many of our peers ? began to develop.

This might be the single hardest concept for white people from communities like ours to accept: Just because the circumstances of our upbringings weren?t as glamorous as those growing up in the wealthy W Towns, we still benefited from white privilege.

For us personally, we never viewed ourselves as having privilege. We grew up in a two-family house. We hung out at the Boys & Girls Club after school. We never used ?summer? as a verb. Once in high school, we spent the majority of our summers working summer jobs. In college, we worked part-time jobs. It was expected. When we met new, wealthy friends in college who didn?t work because ?studying was their full-time job,? and whose parents bought them sports cars for graduation presents, we made fun of them for their privilege.

Back then, we associated privilege solely with socio-economic status. We interpreted our blue-collar background to mean that we had it hard and the rich kids had it easy. What we were forgetting about was the privilege we were born with. The privilege of being able to drive around our city without fear of being pulled over for no reason. Without fear of a police officer shooting us when we reach into our glove box to get our registration. The privilege of being able to walk around stores without security guards following us around, expecting the worst of us. The privilege of being able to go to a doctor?s office or hospital and knowing that our health concerns wouldn?t be downplayed or dismissed. The privilege of being able to call the police in an emergency and knowing that once they arrived they?d see us as people in need of help, not potential criminals.

Those are just a few examples of the privileges we receive automatically as white people, regardless of our socio-economic status.

If you think these privileges are insignificant, you haven?t been paying attention to what?s been happening in this country. Time and time again, access to these types of privileges has literally meant the difference between life and death.

The Takeaway: Whether you are working-class, middle-class, blue-collar, white-collar, low-income, high-income? if you?re white, your whiteness guarantees you certain benefits that people of color do not receive. White privilege doesn?t mean your life hasn?t been hard, it means that your skin color isn?t one of the things making it harder.

2. Your struggle story is NOT the same.

Many of us from working-class cities and towns in the Boston area are the products of immigrant families who came here looking for a better life. Generations later, we continue to pass down their ?struggle stories.? We honor them. We celebrate them. But the fact remains: The struggle stories of white immigrants are not the same as those of people of color.

Boston has large Irish and Italian communities. We?re part of both, like a lot of people from here. We grew up with the stories from both cultures. Italians living in poverty and squalor in the tenements of Boston?s North End. Irish fleeing famine and death at the hands of their English oppressors. Family members changing last names to sound less ?ethnic? and more ?American.? Sending money back home with the hopes of bringing over more family members.

Such stories have an important place in history, but to claim that they are somehow the same as or equal to the stories of Black Americans would be absurd. Yes, the stories of European immigration to the United States are rife with struggle. But it?s important to remember that these stories often began with a choice. A choice to cross the Atlantic and seek a better life. Enslaved Africans did not have that choice. White slavers ripped them from their ancestral homes and brought them here against their will, with countless losing their lives on the journey over. It?s a legacy that started in 1619, predating the arrival of the Pilgrims, predating the arrival of the overwhelming majority of our white ancestors.

The struggle stories of Black Americans continue to this day, some 400+ years later. While slavery in the United States ended in 1865, the systematic oppression of Black people did not. From Jim Crow laws, to the Tulsa massacre, to racial profiling, racial violence and racist policies targeted at Black people are still having a profound effect on Black lives.

Meanwhile, for the descendants of European immigrants, our struggle stories have largely ended. Why? Because a generation or two after arriving, European immigrants no longer seemed like ?others.? Once they learned the language and lost their accents, they largely became indistinguishable from other white Americans.

Black people have never had that luxury.

To this very day, white Americans continue to view Black people as ?others,? and that perception of ?otherness? continues to fuel hatred and bigotry.

The takeaway: Your family likely has a struggle story, but it is NOT the same as what Black Americans have faced over the past four centuries. Acknowledging this does not make your family?s story any less important.

3. No, you don?t ?get it,? but you can still be an ally.

This is the trap that so many white Americans, ourselves included, have fallen into and continue to fall into: When we grow up thinking we don?t have privilege, and that our family histories are filled with the same types of struggles that Black people faced (and continue to face), we end up saying stupid things like, ?Oh, I get it,? when talking about racism.

Or worse, we take it a step further and say things like: ?We don?t see color. We?re all the same. WE are not racist, it?s the other white people.?

Let?s be clear: We don?t get it. And as white Americans, we?ll never get it. We?ll never understand the Black experience in this country because we have not lived the Black experience in this country. Believing otherwise will only serve to perpetuate racism, not end it.

As white Americans, our role in this crisis isn?t to be saviors, our role is to be allies.

What does that mean? Well, for starters, it means speaking out against racism?not speaking over, or on behalf of, Black people, but speaking out.

You can think a lot of nice thoughts about equality and the need for reform, but unless you externalize those thoughts, you are doing nothing to help. You need to speak up. And you need to push yourself outside of your comfort zone.

We?re going to be honest: Some of our friends and family members will read this article and criticize us for it. Decades-long relationships might be damaged, or end completely, because of it.

That?s fine.

It?s time for white people in America, ourselves included, to put our comfort aside and to prioritize the needs of Black people. We need to LISTEN. And then we need to take action (see calls-to-action below).

The Takeaway: As white Americans, we?ll never ?get? the Black experience. We need to avoid devolving into white saviorism and instead serve as allies to the black community.

Calls-to-Action: So, what do I do now?

We?ve all seen the posts online telling us to take action, to stand up and do something. But what exactly does that look like?

Here are a few small steps you can take RIGHT NOW. Pick one, or two, or all of them, and get to work:

- Protest. Join the peaceful demonstrations being organized all around the country. Stand and march in solidarity with Black people.

- Donate. Donate to a local bail fund so you can help peaceful protesters who?ve been arrested get out of jail. Apart from the Philippines, the United States is the only country in the world with a cash bail system that is dominated by commercial bail bondsmen (source). And because Black people are disproportionately targeted by police for arrest, they are affected disproportionately.

- Call. Reach out to your House representative right now and demand that they co-sponsor and push for a vote on a resolution to condemn police brutality, racial profiling, and use of excessive force. Just enter your zip code here to get the phone number of your congressperson and a script you can read on the call.

- Educate yourself. Check out the resources we?ve compiled below. DON?T ask Black people to educate you ? it?s your job to seek out your own education.

Resources: Your White Privilege Education

- An antiracist reading list

- Seeing White

- Spotlight on Racism in Boston

- Boston?s Racist Past Haunts its Present, by Reverend Irene Monroe

- Use your white privilege to fight racism

- Dr. Robin DiAngelo discusses ?White Fragility? (Video) (Book)

- Dr. Carol Anderson discusses ?White Rage? (Video) (Book)

At the very least, we hope this article made you stop and think about racism, the role white people play in perpetuating it, and what you can do to be a better ally to Black people both in the Boston area and around the country. Better still, we hope you talk to your friends and family and keep this conversation going. Now is not the time to be silent. Now is the time for white people, like us, to use our privilege for good.

Thanks for reading.

-Julie Devaney Hogan & Erik Devaney