Introducing the C.O.O.K. Alliance

We recently decided to shut down the Josephine business, but our conviction in the momentum of the home cooking movement only continues to grow. We will be continuing our policy work, including our support of the California Homemade Food Operations Act and other similar efforts around the country, through the C.O.O.K. Alliance (?Creating Opportunities, Opening Kitchens?).

Here?s why we believe that these past few years have just been an early chapter in an important narrative that continues to unfold.

Josephine, a food and labor justice startup

Josephine was never just a tech company. Although we built a web platform and raised venture capital, our founding team openly and deliberately rejected the Silicon Valley-dominated startup narrative. We were public health experts, anti-capitalists, and local organizers, who became proponents of a better ?sharing economy? as a means to an end, not an end in and of itself.

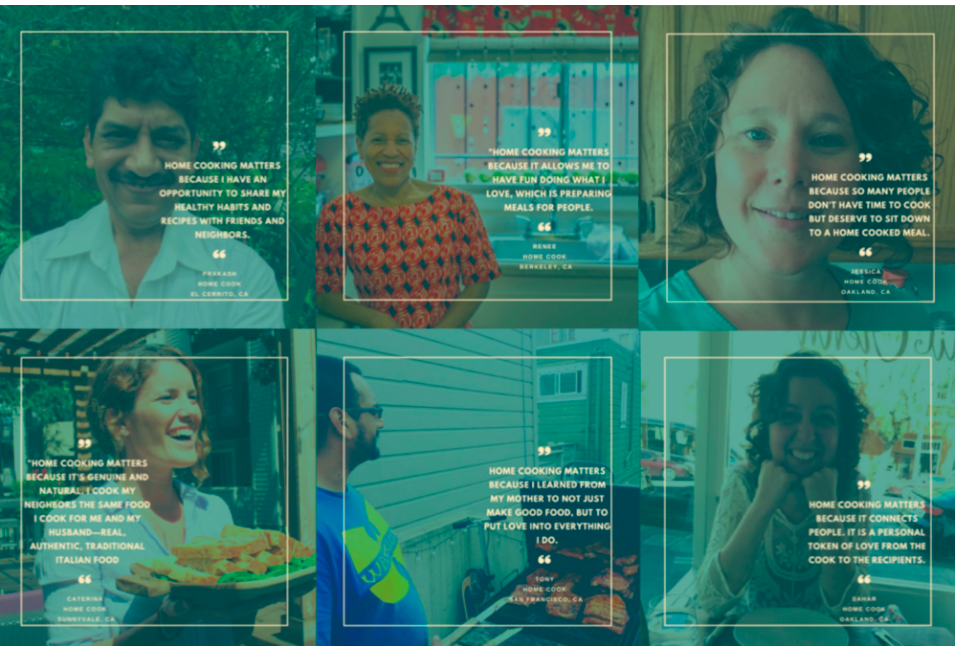

Our mission was to create more inclusive opportunities in the food industry. We worked in gentrifying neighborhoods and helped long-time local residents leverage their community roots and cooking skills to make the money they needed to stay in their communities. An added benefit was that, while earning an income, these cooks could connect with newer (sometimes more affluent) populations ? often busy parents seeking not only healthy food for their families, but connection, trust, and a sense of belonging within their neighborhoods.

In the simplest terms, Josephine was a platform that let folks buy take-out dinner from their neighbors. The model was elegant in that it didn?t need to be explained or over-intellectualized. People recognized good food, and they felt all of the intangible emotional and psychological benefits, even if they couldn?t put words to them. It felt good on multiple levels to pick up a home cooked meal from a neighbor who knew your kids? names and remembered your allergies. From the very beginning, we saw that we could fill a real, recurring, and urgent need felt by many people. And in our first couple of years we served thousands of customers and facilitated the sale of tens of thousands of meals.

But for our team, the success of Josephine would never be measured simply by building a successful business. We were building a movement around home cooks, empathy, and community.

Between 2014 and 2017, we worked with over one thousand home cooks (1). We helped a Vietnamese immigrant leave his job bagging groceries to start sharing the famous C Kho T? recipe from his family?s restaurant in Saigon, supporting local Vietnamese markets in Oakland along the way. We helped a lifetime professional baker find time to look after her grandkids by cooking ?Granny?s grits and bread puddin?? for her extended family and friends in retirement. And we helped a refugee tell her family?s story by serving traditional Iranian Kashe Bademjan to neighbors, while raising money to support other refugees in her community.

The Josephine mission didn?t just resonate with individuals ? we found support from women?s rights, immigrant advocacy, and black empowerment groups as well. We formed unique partnerships in the community, like working with Willard Middle School on a community cooking and gardening program and Bottom?s Up Farm to produce ?farm-to-table? meals from a reclaimed lot in West Oakland. We worked with Food Shift to sell meals cooked by people experiencing homelessness and MarketShare to highlight the struggles and resilience of recent immigrants.

But it wasn?t enough.

The limitations of the ?startup?

For every cook we could work with, there were hundreds we couldn?t. There are millions of experienced cooks in the U.S. and the vast majority cannot independently benefit from their cooking skills due to outdated regulations written for industrial food producers. The high barriers to professional opportunity have in turn created a massive underground food economy where oftentimes normal people don?t even realize they are breaking the law. Think of everything from church fundraiser BBQs to dumplings sold by Chinese grandmothers on WeChat.

Unfortunately, food sales from non-commercial kitchens are treated by many health regulators as criminal violations. Informal food sellers ranging from a single mother of six in Stockton to the famous Thai Temple in Berkeley consistently face threats of fines and even jail time. As a result, many home cooks keep their business quiet or sign up for minimal (and costly!) hours at a shared commercial kitchen to get a business license and insurance, while continuing to do food prep out of their homes.

For every cook who used Josephine, there were dozens more who preferred to stay underground.

A lot of folks simply couldn?t afford to take the risk of publicizing their business ? too many rent payments and education funds depended on this underground economy. Although we offered subsidized commissary kitchen space and a number of our cooks successfully started commercial businesses, the majority had lifestyle constraints like young children, disability, or age, which meant they needed to be at home. Others had already been disillusioned by their experiences in the professional food world.

We did not want to simply evade responsibility in pursuit of growth, but we also didn?t have the resources to be an indefinite front-line of defense for a growing number of cooks in the face of some of the largest institutions in our country. It became obvious that ignoring the larger systemic policies and injustices was myopic ? we were trying to put out the fire on the stove while the house continued to burn. We knew we would need diverse voices, including government partners, to help us ask the right questions.

Policy work followed naturally from community-building.

With the support and power amassed in our community of 50,000 cooks and customers, we began going to city, county, and state government agencies to make a case for updating and improving our food codes and decriminalizing the economic opportunities that were already part of the livelihoods, health, and community fabric of so many people.

In January of 2016, we submitted our first California bill language just a few days before the legislative deadline. It marked the beginning of something we never imagined.

A growing grassroots movement

Since 2016, we?ve been blown away by the sheer number of public health experts, small business coalitions, advocacy groups, and individuals who have joined us in calling for more inclusive food permitting laws. The interest in and support for legislative change are immense.

Over the past two years, we?ve workshopped our approach in dozens of meetings with regulators and policy makers, and in community ?town hall? discussions with cooks and other community members. We?ve received input on our legislative language from legal experts ranging from left-leaning cooperative lawyers to centrist law school programs at Harvard and UCLA, to conservative business groups and the libertarian Institute for Justice. We?ve been invited to present our proposals to elected officials at CityLab and the Aspen Institute and regulators at multiple state-level conferences.

The outpouring of emotional investment and support revealed a movement that was so much bigger than Josephine. We saw that while we were throwing ourselves at a small, specific piece of the problem, others all over the country and world were doing the same. Dozens of organizations from local food policy councils to national advocacy coalitions have signed in support of our California legislation. Over 40,000 individuals have signed our petition. Policy groups hoping to run similar bills in several other states have reached out for assistance. We?ve found ourselves thrust into the center of this movement.

Though encouraging, this also illuminated the extent of the work needed to change a deeply entrenched system.

As 2017 progressed, and our California legislation was held in committee, we began to acknowledge that we might not be able to force a startup-world timeline onto our larger legislative and culture change endeavor. The Josephine business was not yet financially sustainable and our investors hadn?t signed up for a long-term policy effort.

We made the difficult decision to wind the Josephine business down in January 2018 (2). In doing so, we recognized that we had failed to deliver on the hope and faith lent to us by so many people. And we acknowledged that the news would bring very real sadness and disappointment for many folks who had woven Josephine into their lives and have even come to count on Josephine meals, to feed their families or to pay their rent.

But the decision didn?t change who we are or what we committed to.

We still have unwavering conviction in the momentum and potential impact of this movement. And we strongly believe that the Josephine story is just an early chapter in a longer and more important narrative that continues to unfold.

C.O.O.K. Alliance continues this larger movement

Over the past few years, we?ve seen that home cooking can create meaningful and creative jobs that are still relevant in the age of automation. We?ve seen that shared food can reconnect neighborhoods that have otherwise become increasingly atomized and anonymous. We?ve seen that bonds forged face-to-face, on front porches and over the dinner tables, can help dignify under-appreciated work and build power in underrepresented communities.

We created the C.O.O.K. (?Creating Opportunities, Opening Kitchens?) Alliance to continue organizing this movement. While we will no longer be operating a business, or immediately helping cooks sell meals, we will continue to work on the policy changes and resources needed to empower home cooks.

As part of this work, the C.O.O.K. Alliance has become the primary sponsor of California Homemade Food Operations Act (AB 626), which passed the state Assembly with overwhelming bipartisan support last week (3). If AB 626 becomes law, it will be the first bill of its kind in the United States and the C.O.O.K. Alliance will work to support implementation in California as well as create model legislation to encourage similar efforts in other states.

As this movement gathers steam, new organizations and companies are already stepping up to work with home cooks.

We want to ensure that home cooking helps the people who need it most ? the grandmothers cooking grits, the immigrants selling soup, and the refugees sharing stories in the way they know best.

The C.O.O.K. Alliance will always stand for:

Labor Justice: We believe in creating more inclusive opportunities in food for people who need them the most ? stay at home parents, immigrants, and people of underrepresented minority groups. Cooking is a fundamental lever of economic empowerment, and the food industry has taken that away from many through its strict barriers to entry.

Collective Action: We believing in engaging with diverse communities, sponsoring grassroots legislation, and incorporating different stakeholders into advocacy efforts. Cooking should be a tool for solidarity ? better connecting us with our neighbors, bridging socioeconomic divides, and building power in local economies.

What you can do

If you believe in bringing communities together and creating more inclusive opportunities in the food industry, we?re asking you to join us. We need home cooking more than ever and the best answers for how this policy change should unfold will come from a broad coalition of voices.

Specifically, we?re asking you to:

- Call your representative by clicking here.

- Share this post with friends, networks, and organizations that should be supporting the legalization of small-scale home cooked food sales

- Visit cookalliance.org to join our email list or send a note to [email protected] with how you?d like to help

Stand with us for a future where talented home cooks can legally and safely share meals, hospitality, and culture with their neighbors.

Footnotes:

- Cooks using the Josephine platform were approximately 85% were women, 33% were immigrants, and 48% were African, Hispanic, or multiracial. 36% had household incomes of under $45k and the majority saw home cooking as an important source of their family?s income.

- By December of 2017, when an investor failed to wire a signed-and-promised investment of $500k and the Attorney General of Washington unexpectedly issued a subpoena requesting the personal information of our cooks, our team had simply run out of emotional and financial resources.

- AB 626 seeks to create a new permitting process for home kitchens, which would legitimize an important source of income for thousands of families and improve public health safeguards around the existing informal food economy.